Big Data vs Big

Is there enough room in the universe to store all our selfies?

In 1844 Samuel F.B. Morse sent the first official telegram. The slightly ominous biblical phrase ‘What hath God wrought’, chosen by Annie Ellsworth, the young daughter of the Patent Commissioner who helped to fund the invention, heralded a sea change in our ability to communicate information speedily; it was the beginning of the digital age. Words were now being converted into dots and dashes and transmitted.

By 1863, Edward A. Calahan had converted the telegraph into a machine that could reliably transmit and print out stock prices on long rolls of paper. The machine, called a ticker tape because of the clacking sound it made, became so ubiquitous it gave birth to the ticker tape parade: the tradition of cascading used rolls of paper over heroes and dignitaries as they paraded through American cities in open-top cars. Ever since 1863, all we have done is refine the methods of doing the same thing; what was once dots and dashes converted to text on paper is now electrons in a solid-state hard drive converted to legible text on a screen. Once it got going, we never looked back.

Simple messaging has today evolved into telling our personal stories in real time: camera-based recording creatively edited on a smartphone and distributed through various online platforms has become more than commonplace – it’s everywhere. Meanwhile, our digital footprint stamps itself on the world through every interaction we have. Our televisions, fitness devices, games consoles, cars, smartphones and every app we glance at – even our movements at work – are all pouring data into private and public storage devices, where it can be filtered and analyzed by companies and governments to be used in ways that were unimaginable even a decade ago.

We are now storing data at an unprecedented rate, but no matter how commonplace it is to record ourselves or have others record us, there is a lot of confusion about what ‘data’ is and how it is stored. When discussing Big Data, experts throw around terms like ‘bits’, ‘bytes’, ‘megabytes’, ‘terabytes’, or even something called a ‘yotta’, with alarming casualness. Why are these mysterious words so important to understanding the era of Big Data?

We’ll start by looking at how text is stored and see how the size of a computer file grows when we introduce pictures and sound. Then, as information is being stored at an ever-increasing rate, we’ll examine whether we could ever reach the limit of our ability to store data in the near future.

Of bits and bytes…

To understand why Big Data got so big, we need to start at Morse’s telegraph. It was based on the relay switch, where an operator pressed a button connecting two pieces of metal together, allowing an electrical current to pass through a wire wrapped around a soft iron core, turning it into a magnet. The magnet attracted a piece of steel which, in turn, clicked into place completing a circuit. The current then passed down a wire where, at the other end, a similar device was triggered and a rather pleasing ‘click’ was heard.

Morse Code relied on the length of the circuit to produce combinations of dots and dashes to represent letters, but it didn’t change the fact that it was either ‘off’ or ‘on’. This was a big breakthrough: the two off and on states could also be described as 0 or 1 – the basis of the binary system.

The first computers were essentially a giant collection of switches, each one triggering the next in logical order depending on what the initial input was. Think of it like a floor full of mousetraps – once you start off the first, it triggers a reaction in the next and so on. Using switches arranged in the correct sequence – Boolean logic, as it is known – allows you to ask questions like, ‘What is the sum of 4 + 1?’ As the cascade of switches ripples through the system, it eventually outputs a combination of switches indicating the answer ‘5’. Eventually, the relay switch was replaced by tiny circuits printed into semiconducting materials and the silicon chip was born. This process of miniaturization brought speed and power to computing, but the basic principles have never really changed.

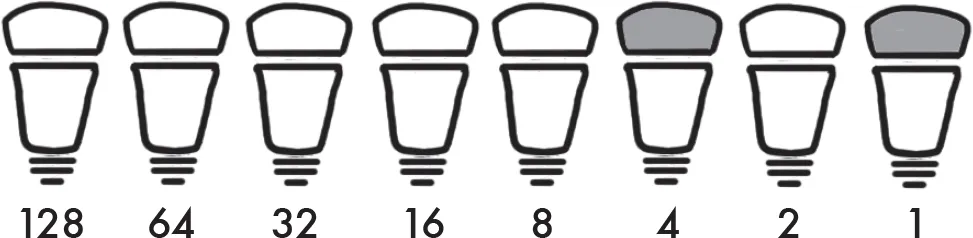

Computing answers is fine if you only want to ask a question once. What about if you want to store the answer? In that case, the computer needs to be able to interpret it as a piece of binary data. To understand how computers use the binary data system to store data, let’s learn to count in binary like a computer does. Forget your usual counting, which moves up a digit each time you ratchet up another ten units (known as base-10). In binary, you step up a digit when the previous number doubles. So instead of the series 1, 10, 100, 1000 etc. in binary the series is 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 etc.

To visualise this think of a row of light bulbs. If the light bulb is off it is represented by a 0 and if it is on it is represented by a 1. The light bulbs are arranged in the same assending order as the binary system and are switched on when we input a base-10 number. By looking at which bulbs are on and off, we can read off what the binary equivalent is. So, the number 5 in base-2 looks like this: