eBook - ePub

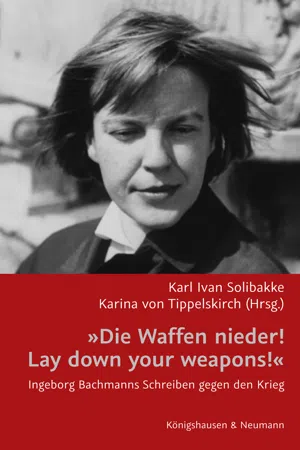

»Die Waffen nieder!/ Lay down your weapons!«

Ingeborg Bachmanns Schreiben gegen den Krieg

- German

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

»Die Waffen nieder!/ Lay down your weapons!«

Ingeborg Bachmanns Schreiben gegen den Krieg

Über dieses Buch

Einleitung – Bachmann rekontextualisiert – G. Brinker-Gabler: "Weiterdenken" - Bachmann, the Public Intellectual – R. Pichl: I. Bachmanns ironisches Konzept – S. Lennox: The Transnational Bachmann – K. Achberger: I. Bachmann: Composing after Ausschwitz – Bachmann und das Judentum – M. Anderson: A Delicate Affair: The Young Ingeborg Bachmann – B. Witte: "Ich liebe Dich und ich will Dich nicht lieben" - I. Bachmann und Paul Celan im Briefwechsel – V. Liska: Two Kinds of Strangers: The Correspondence between I. Bachmann and Paul Celan – Y.-A. Chon: "Feingewirkt, durchwebt" - Wechselseitige Bespiegelung zwischen Celan und Bachmann – K. Krick-Aigner: "Our eyes are opened" - I. Bachman's Writing on the Holocaust as Testimony – "Böhmen liegt am Meer" und andere Gedichte – S. Gölz: "Böhmen liegt am Meer" - Die Heimkehr in den Grund – P. Gilgen: I. Bachmann's War: Between Philosophy and Poetry – K. von Tippelskirch: Angrenzen: Anselm Kiefer und I. Bachmann – S. Giannini: In Pursuit of Allegria: I. Bachmann meets Giuseppe Ungaretti – Interpretationen – P. Beicken: "Grab ohne Auferstehung" - I. Bachmanns Schreiben gegen Gewalt und Krieg – H. Schreckenberger: I. Bachmann's Radio Play Ein Geschäft mit Träumen in the Context of Post-War Austria – K. Solibakke: "Fest steht der Schrei" - Zur Krise der Wahrheit in I. Bachmanns Ein Wildermuth – D. Lorenz: Visions of Violence in the Austrian Landscape in Bachmann's Three Paths to the Lake and Clemens Eich's Sea of Stone: Two Writers in Discourse with War and Fascism

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Ja, du kannst dein Abo jederzeit über den Tab Abo in deinen Kontoeinstellungen auf der Perlego-Website kündigen. Dein Abo bleibt bis zum Ende deines aktuellen Abrechnungszeitraums aktiv. Erfahre, wie du dein Abo kündigen kannst.

Nein, Bücher können nicht als externe Dateien, z. B. PDFs, zur Verwendung außerhalb von Perlego heruntergeladen werden. Du kannst jedoch Bücher in der Perlego-App herunterladen, um sie offline auf deinem Smartphone oder Tablet zu lesen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Perlego bietet zwei Abopläne an: Elementar und Erweitert

- Elementar ist ideal für Lernende und Profis, die sich mit einer Vielzahl von Themen beschäftigen möchten. Erhalte Zugang zur Basic-Bibliothek mit über 800.000 vertrauenswürdigen Titeln und Bestsellern in den Bereichen Wirtschaft, persönliche Weiterentwicklung und Geisteswissenschaften. Enthält unbegrenzte Lesezeit und die Standardstimme für die Funktion „Vorlesen“.

- Pro: Perfekt für fortgeschrittene Lernende und Forscher, die einen vollständigen, uneingeschränkten Zugang benötigen. Schalte über 1,4 Millionen Bücher zu Hunderten von Themen frei, darunter akademische und hochspezialisierte Titel. Das Pro-Abo umfasst auch erweiterte Funktionen wie Premium-Vorlesen und den Recherche-Assistenten.

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen bei deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ja! Du kannst die Perlego-App sowohl auf iOS- als auch auf Android-Geräten nutzen, damit du jederzeit und überall lesen kannst – sogar offline. Perfekt für den Weg zur Arbeit oder wenn du unterwegs bist.

Bitte beachte, dass wir Geräte, auf denen die Betriebssysteme iOS 13 und Android 7 oder noch ältere Versionen ausgeführt werden, nicht unterstützen können. Mehr über die Verwendung der App erfahren.

Bitte beachte, dass wir Geräte, auf denen die Betriebssysteme iOS 13 und Android 7 oder noch ältere Versionen ausgeführt werden, nicht unterstützen können. Mehr über die Verwendung der App erfahren.

Ja, du hast Zugang zu »Die Waffen nieder!/ Lay down your weapons!« von Karl Ivan Solibakke, Karina Tippelskirch, Karl Ivan Solibakke,Karina Tippelskirch im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Thema

LinguisticsA Delicate Affair: The Young Ingeborg Bachmann

I.

When I first began reading and translating the writings of Ingeborg Bachmann in the early 1980s, the notion of two separate authorial personae was a firmly entrenched, if relatively recent, position among academic critics: the aestheticist poet of the 1950s versus the politically engaged prose writer of the 1960s and 1970s; the shy young Austrian “poetessa” championed by the male literary establishment who saw in her the continuation of a classical tradition reaching back to Rilke, Hölderlin and Goethe versus “die andere Bachmann” heralded by Sigrid Weigel, Christa Wolf and others who emphasized her feminist commitment to the description of “new forms of suffering.”1 At the time, I found this opposition, excitingly polemical as it might have been, unfair. I had begun translating Bachmann together with the work of Celan, and although at the time few people knew the extent of their personal relationship, the two seemed to fit together in the way their poems gave voice to an underlying sense of historical crimes and political realities even as they maintained a soberly existentialist, unsentimental sense of human relationships, nature and myth. Still, this was a minority point of view at a time when German feminism in American academia was really taking off. For many of my graduate student peers, Bachmann’s poems had moved to the periphery: the “real” Bachmann, the real center was now the sprawling, unfinished prose cycle called the Todesarten, and especially the terrifying dream sequences in the “cemetery of the murdered daughters” in which the Holocaust and patriarchy, Jewish and female suffering were inextricably entwined.

Since the publication of Bachmann’s personal correspondence with Celan in 2008 and, two years later, her so-called “war diary” and the letters to her by Jack Hamesh, we are in a position to see that her awareness of the victims’ perspective of National Socialism began as soon as the war was over and that, far from being an abstract, generational awareness typical of the postwar period, it was immediately and scandalously personal. “Sie geht mit dem Juden” (“she’s going out with the Jew”): this was the reproach that the not yet nineteen-year-old Bachmann could hear from her family and neighbors about her relationship with the British intelligence officer and Viennese-Jewish emigrant Jack Hamesh, which began in June 1945, even before Bachmann’s father had returned from the war (KT, 22). For half a century Bachmann’s readers had assumed that her critical perspective on the Nazi period began during her university years in Vienna when she first met Jewish survivors of the war like Ilse Aichinger, Hans Weigel, Hermann Hakel and, briefly, on his way from Bucarest to Paris, Paul Celan: professional, collegial friendships with other writers and critics. Now we can see that the core of the Todesarten, the entwining of female and Jewish victimhood, is part and parcel of her own personal and sexual development in momentous, early love affairs with at least three Jewish survivors of the Holocaust: Hamesh, Celan and—another surprise—the Austrian-Jewish critic Hans Weigel.

I am not Bachmann’s biographer and have no wish to enter into intimate matters merely for the sake of personal curiosity. It is always a delicate matter to speak of post-Holocaust relations between Jews and Germans (or Austrians), and all the more so in the case of a writer like Bachmann who sought to keep her own personal life out of the public spotlight. Nonetheless, the recent publications shed light on an area of her life and work that has received surprisingly scant biographical and critical attention, namely, the period before her literary breakthrough to a broad German-speaking audience in the early 1950s. Bachmann began writing seriously, with an eye toward publication, in the early years of the war. In the decade before her appearance in Niendorf in 1952 for the Gruppe 47, she wrote a full-length historical drama, numerous short stories, an extensive historical novella and hundreds of poems; few of these writings found their way into the Werkausgabe of 1978, which has remained the only comprehensive edition of her work for more than thirty years. So different is this image of the young Bachmann, both in literary and biographical terms, that one is tempted to speak of a third authorial persona—one that is distinctly regionalist, and aesthetically as well as politically conservative. But too few of these early texts, some of which Bachmann published or tried to publish, are generally accessible—there is no edition of Bachmann’s early writings. There are also frustrating gaps in our biographical knowledge. Access to her personal writings besides the correspondence with Celan and the (tantalizingly brief) war diary is blocked until 2023. We also do not have Bachmann’s letters to Hamesh and the so-called “war diary” begins and ends abruptly, suggesting that a larger diary may have existed or that it is not quite the personal diary it appears to be.2 Bachmann’s apparently extensive correspondence with Hans Weigel is also not accessible to the general public, and critics and biographers alike tend to give the relationship—which lasted several years, helped pave the way for Bachmann’s literary success in Germany, and gave her direct and extensive understanding of the Austrian-Jewish catastrophe—surprisingly short shrift.

Still more intractable is the problem of Bachmann’s own ambiguity and omissions with regard to the past, both in her literary writings as well as her biographical statements and interviews. “Jugend in einer österreichischen Stadt” is perhaps the most obvious example of this ambiguity: a text that names the very streets in Klagenfurt where Bachmann grew up, a text whose final paragraph invokes the language of a historical witness to the war—“Weil ich, in jener Zeit, an jenem Ort, unter Kindern war [...] nehme [ich] zu Zeugen” (IBW II, 92)—is also a text that speaks of “die Kinder” rather than “wir Kinder.” The same ambiguity holds for the question of “her” or “the” father in the literary texts: on the one hand the horrifying sequences in the “imaginary autobiography” Malina where “the father” appears as the sadistic Nazi Kommandant whose handiwork results in an entire cemetery of murdered daughters; and on the other hand, the testimony of family members and close friends who repeatedly stress Bachmann’s “excellent” relationship with her “real” father.

Compounding the paradoxes of the “imaginary autobiography” in her literary texts are the silences that Bachmann maintained about her actual biography, starting with the relationship with her father. Few biographers doubt his importance in her early development. He encouraged her as a writer at an early stage, giving her for instance the documentary material for her early historical novella “Das Honditschkreuz.” His love of Italy shaped her lifelong interest in its language and culture. He supported her decision to leave Klagenfurt and study at the university, even taking out a loan on the family house to help finance her. Their close relationship (and occasional financial dependence when Bachmann’s prize money and honoraria ran out) continued to the end of her life. He is transformed into a recognizable (and likable) character in her novella “Drei Wege zum See,” the last work she ever published, where he appears as the genial antithesis to the annoying German tourists in the story’s present-tense and as a symbolic link to pre-WWI Habsburg Austria. The bond was so strong that in biographical statements as well as in literary texts from the earliest period to the Todesarten project Bachmann identifies her own origins not in Klagenfurt or with her mother’s family but with the paternal ancestral home in the Gail Valley.

During her lifetime Bachmann continued to uphold this image of the “good father,” never publicly referring to his role in the war or to his political beliefs other than to suggest that he and the family had opposed Hitler and the Anschluss. It took biographers half a century, almost twenty years after her death, to discover that Matthias Bachmann had joined the Nazi Party in 1932, six years before Austria became part of the Third Reich. A veteran of the First World War, he voluntarily enlisted on 31 August 1939—he was then forty-four years old, and his only son had just been born—and served as an officer in the Wehrmacht throughout the war. He was held prisoner by the Americans until the fall of 1945 and barred from teaching for his political activities for a significant period after the war.

Bachmann also never publicly acknowledged her relationship with Josef Friedrich Perkonig, whose influence has similarly been ignored or downplayed by most critics and biographers. But Perkonig, Bachmann’s German teacher at the Pedagogical Institute and then Carinthia’s most important writer, played an extraordinary role in Bachmann’s life at a time when her officer father was largely absent, influencing her writing and becoming a kind of ideal, inaccessible love object.3 He was also, like Matthias Bachmann, a committed Nazi. As Klaus Amann has shown, Perkonig’s self-representation after the war, distancing himself from the National Socialists, misrepresents his actual activities. A member of the Nazi Party after 1934, he greeted the retreat of the Schuschnigg government on 11 March 1938 as a moment of pure joy for himself and his country: “Und es war mir dann, da ich auf die Strasse hinaushorchte, als spränge das Land in die Sterne hinein. Ich spürte beinahe körperlich das Glück dieses Abends. . .” (IBW II, 147). Countering the revisionist claim that Perkonig suffered professionally during the Nazi regime, Amann notes that his literary and political careers both prospered. He received official invitations to the Weimar Poets Gathering of 1940 under the patronage of Goebbels, to the Salzburg Dichterwoche in 1940 and 1942, and to the occupied territories of Croatia, where he was received by the commanding general. He served in various political offices, including the office of retribution for the Gau Carinthia. In this capacity, writes Amann, he was charged by the Party to provide compensation for Party members who had suffered damages before the Anschluss in the

Kampfe für Führer und Reich: Für diese Zwecke wurde dem Gau Kärnten ein Betrag von insgesamt 3,6 Millionen Reichsmark zur Verfügung gestellt, der größtenteils aus der Einziehung sogenannten ‘staatsfeindlichen’ [i.e. jüdischen] Vermögens finanziert wurde.4

What Bachmann may have known of Perkonig’s many official activities is unclear, but it is hard to believe that such a committed participant in the German national cause would have remained quiet about his political views in the classroom. Indeed, in 1942 Perkonig published a propagandistic schoolbook for children in Carinthia explaining, among other matters, their duty to lay down their lives to the Führer:

Einmal, deutscher Knabe, deutsches Mädchen, wirst du erwachsen sein und deinen Platz im deutschen Volke einnehmen. Denke immer daran, daß du auf der Welt bist, um deinem Volke zu dienen, nicht aber, um ein bequemes Leben zu haben. Du hast das Glück, einem herrlichen Volk anzugehören...Als es in Not und Schmach geriet, da schenkte ihm Gott einen Führer, der es wieder in das Licht führte. Ihm mußt du in Leben und Tod ergeben sein...Gib für Deutschland Glück und Gut dahin und, wenn es sein muß, auch das Leben.5

Given this identification with these two paternal figures, but also given the turn in ...

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Decke

- Half Titel

- Titel Seite

- Copyright

- Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Einleitung

- Bachmann rekontextualisiert

- Bachmann und das Judentum

- „Böhmen liegt am Meer“ und andere Gedichte

- Interpretationen