1

The closer one gets to Benin, the farther away it is

They wave their arms in the direction of the palace, wailing and shouting. There are some fifty of them, men and women standing in separate groups, dressed in traditional robes. They have travelled to the palace from surrounding villages as supplicants, hoping the Oba will hear their case. They could have gone to the law courts, but they prefer to come here, for they revere the Oba. Perhaps they want him to mediate in a family feud, or a dispute between neighbours over a piece of land, or an issue of traditional protocol – whether such and such a person may conduct a ceremony even if they are not a chief. But for now, they must wait. They are held back by a fence. On the other side, guards look on indifferently, rifles hanging at their feet. Palace chiefs, distinguished by their white robes and orange-red coral necklaces, lounge in the shade by the entrance of the two-storey neoclassical building. They can hear the cries – they look up each time these reach a crescendo of distress – but they make no effort to be helpful.

As a distinguished historian of Benin, Philip Igbafe, put it, ‘there is much that is old in the New Benin’.1 The old chieftaincy titles are still used, the old ceremonies and customs still practised. People pray in church in the morning, but they take care to worship at ancestral shrines in the evening. The palace compound sits in the very centre of the city, just as it always has done, six roads converging on the adjacent King’s Square from the different points of the compass. The metal gates to the palace are silver-coloured, decorated with motifs of elephant heads, eagles and the faces of elegant queens. Palace wards, or perhaps just young men who pretend to be, hover by these gates. They whisper of special access and a guaranteed appointment with an important person within, as others might do outside a Nigerian airport, or a government ministry, or a telecoms office. They explain with sincere faces that there is a pain-free shortcut on offer, but it will cost a small fee.

When the Oba is ready, he will listen sympathetically to the stories of his subjects, pronounce judgment, and they will accept his verdict. À dàa̒ nọ̒ba̒ ọ̀ ọ̒rè ìfùẹrò ọ̒ghe̒ a̒rrè mwa̒; ‘The fear of the King is the wisdom of our culture.’ So I’m told by Patrick Oronsaye, a genial man in his sixties, whom I meet one Sunday morning in Benin City.2 He is an artist, an historian and a philanthropist. He is also royalty; like Prince Gregory Akenzua, he is a great-grandson of Ovonramwen, the Oba overthrown by the British in 1897. When Patrick speaks of Benin’s history, he gets animated. Names and dates and anecdotes tumble out in quick succession, a dense tangle of local and Western cultural references. It’s hard to keep track, all the more so because of the interruptions from Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, the ring tone on his ever-buzzing mobile phone. His history is littered with phrases of communal lore illustrating the Oba’s tight hold over Benin society. Òha̒ i̒ gu̒ o̒ghi̒ọnba̒; ‘There is no hiding place for the Oba’s enemy.’ Ta̒ gà ọ̒ba̒, ta̒ go̒wa̒àn ẹ̒bọ̀, ta̒ rù ẹ̀ri̒nmwì, ta̒ rù e̒sù; ‘You worship the Oba, you placate a deity, you venerate the ancestors, and you appease the devil.’ And instead of saying that an Oba has died, a Benin man prefers to talk in metaphors: Ẹ̀kpẹ̀n vbìẹ̒; ‘The Leopard is sleeping’; or Òso̒rhùe bùu̒nrùn; ‘The White Chalk has broken’; or simply, Òwẹ̀n de̒ òku̒n; ‘The sun has set.’

Benin City’s traffic-clogged and potholed streets, its hazy polluted air, its sprawl and red-rust metal roofs don’t always evoke past glories. I first visited twenty years ago, to see its famed earth wall, which dates to the thirteenth century and rings the city with a circumference of some eleven kilometres. Archaeologists have measured a height of more than seventeen metres from its top to the bottom of the adjacent moat.3 It is compelling evidence of how Benin’s rulers could mobilise manpower; one archaeologist estimated that if the wall had been built in a single dry season, it would have required 5,000 men to work for ten hours each day.4 It is listed as a Nigerian National Monument. Unfortunately, this offers no protection, as I discovered on that first trip. Rogue constructors dug away at the earthworks with impunity, looking for house-building material in the red, clayey sub-soil of the banks, and rubbish accumulated in the moat. Twenty years later, it was in an even more pitiful state. At a junction on the Sokponba Road, beneath a heaving market, the wall was obscured by five billboards celebrating evangelical churches. The pastors and their wives, in garish outfits, looked down from the posters with compassionate expressions. I ducked under the billboards, away from the shouts of the traders, the music, car horns and revving engines, and climbed gingerly up the earth bank, holding onto bushes for balance. The ground was coated with the slime of human excrement and plastic bags. When I reached the top I saw that the moat on the far side was full of sewage. Everything stank.

Benin’s historic earth walls – today sadly neglected.

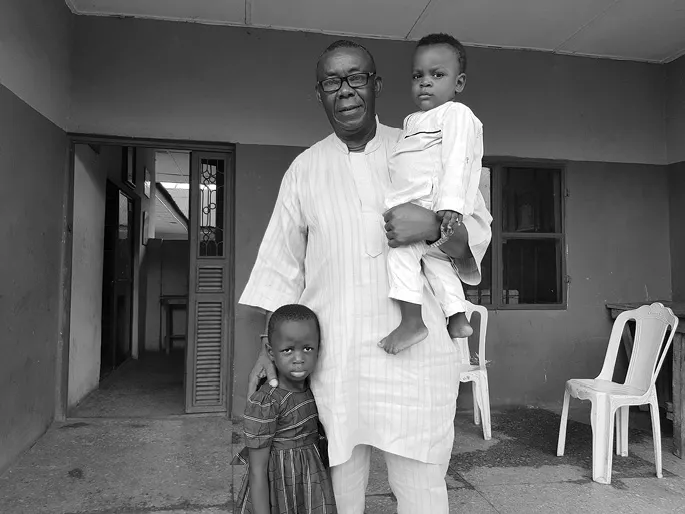

This degrading sight jarred with the picture Patrick Oronsaye was painting for me, of Benin as a society of intricate hierarchies and elaborate rituals, of old customs and beliefs rigidly adhered to. And yet Patrick also conceded that some traditions were under strain. We were meeting in the orphanage his mother had founded in 1951, and which he’d taken over upon her death. In the early days, Patrick explained, the typical child brought to the orphanage had a single mother who had died in childbirth. But after the economic downturn of the 1980s and 1990s, something changed. Parents started to abandon their own children. ‘For the first time, the centre does not hold. The extended family concept has died. Every man for himself. People find children on the street and bring them to us,’ said Patrick, pointing to a solemn little girl in a blue dress who had emerged from the gloomy building behind us. She was perhaps three years old and held tightly to Patrick’s leg. ‘Try telling her I’m not her father,’ he said. She had been left with him when she was five days old. ‘People are throwing away their children.’

Patrick Oronsaye, artist, historian and philanthropist, at his Benin City orphanage.

Patrick is a born raconteur. He could talk and talk, about the great Obas of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the breadth and reach of the Benin Empire at its zenith, the art and culture of the court at its centre, its achievements and its cruelties, the forests and animals which surrounded it. But any conversation about Benin and history inevitably leads back to one fateful year, to a certain Vice-Consul Phillips brushing aside the warnings and marching into the forest, and to everything that followed. 1897. Before and after. ‘A world turned upside down,’ says Patrick. There is, he adds, another saying about Benin’s history. E̒bò rhìa o̒tọ̀, rhìa u̒khùnmwù kèvbè èmwi̒ hìa ra̒; ‘The British man has spoilt the earth and he has spoilt the skies – he has ruined everything.’

If you walk from the Oba’s palace, it might take you five minutes to reach Igun Street. Much depends on the traffic around Benin City’s central roundabout – whether it fleetingly relents and you have the courage to plunge through the cars, buses and motorbikes, and ignore their urgent horns. At the turning for Sokponba Road, you’ll pass a statue, erected in the 1980s. A Benin warrior, cast in dark metal and carrying a spear and shield, stands triumphant, a silhouette against the harsh bright sky. At his feet are strewn four British soldiers. Three are slumped and clutch their stomachs in agony, the fourth has collapsed and appears to be dead. The statue captures a moment of heroism from 1897, even if the invaders’ uniforms and weapons appear more Second World War than late-Victorian. Asoro, the Oba’s trusted warrior, is said to have fought valiantly at this spot, slaying the enemy until finally he too fell. From a crushing defeat, the statue seems to say, an eventual victory emerged. Benin did not die. Asoro’s battle cry – So̒kpọ̒nba̒; ‘Only the Oba dare pass this spot’ – has been immortalised with the naming of the Sokponba Road.

Igun Street, the next turning on the left, was there long before the British marched in. You enter through a red arch inscribed with the words ‘Guild of Benin Bronze Casters, World Heritage Site’. The street runs ramrod straight, lined by modest single-storey clay houses. The casters and craftsmen display their wares on the front terraces; rows and rows of twice life-size brass leopards, American bald eagles, Greek and Roman gods and mermaids, monstrously long brass tusks, shiny icons of Benin history glued onto wooden or red felt backgrounds, wooden giraffes and paintings of scantily dressed women. Christian, classical and Benin traditions are carelessly merged together. It’s easy to be unkind about what Igun Street has become, and many are. Young artists in Benin or Lagos, and the more discerning expatriates in Lagos, dismiss most of its offerings as kitsch, ‘tourist’ or ‘airport art’. One long-time American observer of Benin City likened the street to Tijuana.5 Even Igun Street’s claim to global recognition is dubious – when I checked the website of UNESCO, the body which awards World He...