eBook - ePub

Art History: The Basics

Diana Newall, Grant Pooke

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 296 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Art History: The Basics

Diana Newall, Grant Pooke

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Now in its second edition, this volume is an accessible introduction to the history of art. Using an international range of examples, it provides the reader with a toolkit of concepts, ideas and methods relevant to understanding art history.

This new edition is fully updated with colour illustrations, increased coverage of non-western art and extended discussions of contemporary art theory. It introduces key ideas, issues and debates, exploring questions such as:

-

- What is art and what is meant by art history?

-

- What approaches and methodologies are used to interpret and evaluate art?

-

- How have ideas regarding medium, gender, identity and difference informed representation?

-

- What perspectives can psychoanalysis, semiotics and social art histories bring to the study of the discipline?

-

- How are the processes of postcolonialism, decolonisation and globalisation changing approaches to art history?

Complete with helpful subject summaries, a glossary, suggestions for future reading and guidance on relevant image archives, this book is an ideal starting point for anyone studying art history as well as general readers with an interest in the subject.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Art History: The Basics als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Art History: The Basics von Diana Newall, Grant Pooke im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Art & History of Art. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

ART HISTORIES AND ART THEORIES

INTRODUCTION

Among the accepted entries for the Royal Academy’s (RA) 250th Summer Exhibition in 2018 was Katie Walker’s work, Fragile (2018, Figure 1, p. 2). Fashioned by Walker, a contemporary furniture designer, Fragile is a customised wooden pallet painted blue. Discussing its conception, Walker noted:

I decided to create a wholly unfunctional piece. I love the unfussiness, the utilitarian aesthetic, the honesty of the humble every day object, of the universal pallet – ‘throw away’ yet so intrinsically valuable to society – the unseen supporter. I became a champion of the everyday and fell in love with the colour blue.

(http://www.katiewalkerfurniture.com/news/2018-06-01-Summer_2018.html)

At first glance, the work has few of the conventional characteristics of ‘fine art’. Walker observed ‘plenty of comments about how the packaging was left out’. However, the nuanced meanings which she ascribes to the work signify some of the shifts in art, its interpretation and expansiveness with which this book is centrally concerned. It might also be seen as reflecting changes to the Royal Academy’s curatorial ambitions, with the appointment of a new generation of Royal Academicians, including Grayson Perry (b. 1960) who curated this milestone exhibition.

Figure 1 Katie Walker, Fragile, 2018, [wood, paint], 16 × 100 × 120 cm. © Katie Walker.

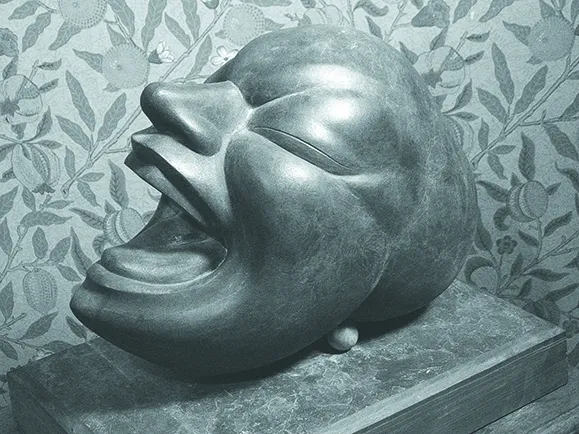

The role of the institution in defining art was emphasised by an earlier RA Summer Exhibition selection involving the work of another artist, David Hensel (b. 1945). His submission, One Day Closer to Paradise, (2006, Figure 2, p. 3), a jesmonite laughing head on a slate plinth with a bone-shaped wooden rest, did not appear to have been accepted when he received the returned head, which had been accidentally separated from the plinth and rest during handling. The remaining elements were exhibited and subsequently renamed Another Day Closer to Paradise (Figure 3, p. 3). It was later auctioned with a donation made to charity. Hensel commented, ‘I’m delighted to have made an empty plinth that isn’t empty, where the exhibit itself is merely invisible.’ This widely reported incident occurred in 2006 (Malvern 2006: 4–5). Hensel further reflected:

the art world itself seems to be engaged in a cultural performance about our times, a parody about duplicity, marketing tactics, and acquiescence.

Presenting this work in public and watching the reactions has produced many fascinating insights into how the arts work, about the need for understanding the broader picture of the dynamics of culture, and particularly the need to study the history of propaganda and patronage, the pursuit of invisible influence, in parallel to the study of a history of art.

(Letter from David Hensel, 1 December 2006; in Malvern 2006: 4–5)

Figure 2 David Hensel, One Day Closer to Paradise, 2006, jesmonite, slate and boxwood base, 44 × 33 × 22 cm. © David Hensel.

Figure 3 David Hensel, Another Day Closer to Paradise, 2006, slate and boxwood base, 44 × 33 × 22 cm. © David Hensel.

Figure 4 Apollo Belvedere, attributed to Leochares, c. ce 120–140. Vatican Museum, Rome. Photo Scala, Florence.

Critics and commentators claimed that the treatment of Hensel’s RA submission demonstrated the ‘emperor’s new clothes’ syndrome, although, as with Walker’s more recent example, the jury’s selection suggested just how arbitrary some ideas about contemporary art and aesthetics are.

As a postscript, Hensel submitted Bad Dog (mixed media, 2007) to the 2007 RA Summer Exhibition. The work featured a stylised pink blind guide dog standing on a replica of the plinth and golden bone-shaped rest, positioned behind the dog and suggestive of a canine deposit. This triggered a ‘sardonic’ comment recalling the events of the previous year (quoted in Hensel 2020).

Using these examples as points of departure, it might reasonably be asked what is actually meant by art and art history? These are two of the central debates around which this book has been written. This chapter will consider some of the changing ideas regarding art and its interpretation. What are the origins of art history as an academic discipline and how has it evolved? How might we evaluate and assess some of the developments of recent decades within the academic discipline and discourse of art history?

What is art?

The various categories and art media discussed in this book – including ceramics, constructions, paintings, land art, installations, performance art, photomontage, textiles and sculpture – all make claim for aesthetic status and/or conceptual value. The label ‘art’ therefore connects very disparate objects, practices and processes. Recognising this diversity, various categorisations have been made within definitions of visual art (including Fernie 1995: 326). From these, we might propose an opening set of guidelines and definitions for understanding art:

- Fine art was traditionally used to distinguish arts promoted by the academy, including painting, drawing and sculpture, from craft- or design-based arts. The latter typically referred to works created for a function – such as ceramics, jewellery, textiles, needlework, furniture and glass, which are still widely termed decorative arts. As the above art works suggest, this distinction is less apparent with contemporary art where a wide variety of media are used. More recently, these boundaries have begun to dissolve as broader concepts of material culture, encompassing the physical traces of cultures across art and design, have become a mainstream focus of art historical study.

- A broader definition of art encompasses those activities which produce works with aesthetic and use value, including film making, performance and architecture. For example, architecture has always had a close connection to painting, drawing and sculpture, two instances being the classical revival in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and the Bauhaus aesthetic of the 1930s which frequently integrated fine art with design, craft and architecture.

- Contemporary definitions of art are not medium-specific (as ideas around fine art tended to be) or particularly restrictive about aesthetic value and the purpose of art (as versions of modernism were – see Chapter 2). These ideas can be associated with the Institutional Theory of Art, which remains a widely used definition. It recognises that art can be a term designated by the artist and by the institutions of the art world, rather than by any further or external process of validation. On the one hand it provides an expansive framework for understanding diverse art practices, but on the other its breadth renders it problematic in other ways (see Chapter 7).

However, regardless of categorisation, all definitions of art are mediated through culture, difference, history and language. There is increasing sensitivity regarding the usage of these terms. For example, in January 2020, Arts Council England (ACE) formally advised that it would henceforth refer to ‘creative practitioners’ in preference to the term ‘artist’ because of concerns around inclusion and accessibility (Wace 2020; ACE 2021). To understand these differing concepts of art, it is useful to consider their social and cultural origins.

What is art history?

Art history has been described as the ‘discipline that examines the history of art and artefacts’ (Pointon 1997: 21). Like many definitions, it verges on the tautological, but Pointon succinctly registers the expansive scope of study which typifies the discipline – those objects and practices arising from human agency which are judged to have aesthetic, and conceptual, value. Eric Fernie (b. 1939) defines art history as the ‘historical study of those made objects which are presumed to have a visual content’, with the task of the art historian being to explain ‘why such objects look as they do’ (Fernie 1995: 326–327). He elaborates various examples, and concludes:

These objects can be treated as, among other things, conveyors of aesthetic and intellectual pleasure, as abstract form, as social products, and as expressions of cultures and ideologies.

(Fernie 1995: 327)

These definitions underline the extent to which art can sustain a multiplicity of meanings, and that in attempting to interpret details of form and content, the art historian is inevitably concerned with broader issues of social context, causation and value. Exploring how art looks or appears is just part of a wider interpretative framework, within which there are various methodological approaches which are neither value free nor impartial.

The classical concept of ‘art’

Western European art, understood as a practical, aesthetic, craft-based activity, has a durable history over millennia. Within Greek culture (first millennium bce), there was no word or concept approximating to our understanding of ‘art’ or ‘artist’. The Greek word techne denoted a skill or craft, and technites a craft-worker who made objects for particular purposes and occasions (Sörbom 2002: 24). Similarly, within the classical world, examples of craft, such as statues and mosaics, had practical, public and formal ceremonial roles. The Apollo Belvedere (c. 120–140 ce, Figure 4, p. 8), a Roman sculpture which draws strongly on the aesthetic values of Classical Greece (fifth century bce), illustrates the importance of a naturalistic representation of the human body. It would have been judged according to the technical standard demonstrated, and by the extent to which it fulfilled the social and civic roles expected of craft. Foremost of these was the belief that the human form should be represented in its most life-like and vital sense as the union of body and soul (Sörbom 2002: 26). The idea that a sculpture or mosaic should be judged on criteria independent of such purposes was alien to the classical concept of craft.

BCE AND CE

In response to concerns over the Christian signification of bc (Before Christ) and ad (Anno Domini – in the year of our Lord), contemporary scholars use bce (Before the Common Era, equivalent to bc) and ce (Common Era, equivalent to ad).

Within a western tradition of art, originating from Greek and Roman practice, the categories of art and craft operated within specific contexts and cultures, and in relation to particular audiences. Throughout Europe and North America, for example, cultural assumptions about what art customarily was were closely linked to the development of art history as an academic subject. To designate something as art implies some kind of evaluative judgement regarding the image, object or process under consideration. But it is important to understand that the meaning and attributions of art are particular to different contexts, societies and periods. Ideas and definitions of art are neither timeless nor beyond history but relate to the social and cultural assumptions of the societies and environments which fashion and apply them.

Plato’s idea of mimesis

The idea of art as the imitation of nature can be traced back to book ten of Plato’s (429?–347 bce) The Republic, c. 340 bce (Sheppard 1987: 5–9). Here, Plato dismissed painting, understood as mimesis or imitation, as having limited use; a painting of a table was neither the ideal form of the table (the perfect idea of a table which existed in divine imagination) nor the table made in a carpenter’s workshop. According to Plato, a painting of a table was merely a copy and had limited practical value since it could not be used to actually make or design a real table (Plato 1987: 424–426). Although else...