![]()

![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE INVENTION AND INNOVATION OF MOTION PICTURES

Introduction

Leading up to Motion Pictures: The Magic Lantern

Thomas Alva Edison: Us Inventor

Innovating Projection: The LumiÈre Brothers

Patent Wars and New Strategies

Movie Exhibition: Through Vaudeville

Movie Exhibition: Through Fairs

Towards The Nickelodeon

The “Cinema of Attractions”

Patent-Free Movies In The USA

Around The World

Film Distribution Model

Case study 1: Who went to see early movies in the USA?

INTRODUCTION

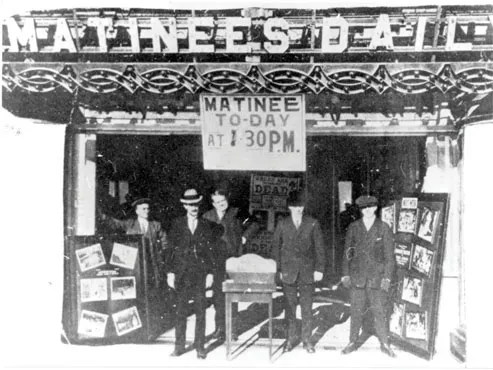

1.1 An early cinema.

This chapter starts by explaining how motion pictures came to be invented and how this technology spread around the world, focusing on the inventions and business strategies of two of the most influential inventors: Thomas Edison of the United States, and the brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière of France. They created devices to record and then project movies – the essential elements for the industry to develop.

In the USA movies became part of the program of vaudeville theaters; in Europe they were spread through fairs. By 1910 theaters especially designed for the projection of movies had become the dominant place to show movies.

Vaudeville theaters offered a selection of variety acts from singers to dancers, from comics to animal tricks. The first vaudeville theater in New York (USA) was the Bowery theater, opened in 1865 and aimed at a family audience. They became very popular and were called variety shows in music halls in Europe.

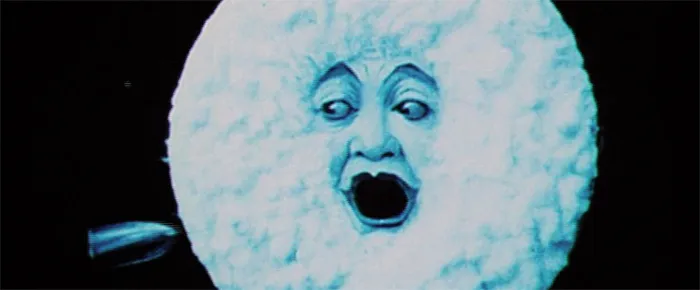

The first filmmakers sought for the best ways to capture images that would interest potential audiences. Scenes of everyday life, news subjects, travelogues, recorded theater performances were amongst the earliest subjects. Soon after that came comic narratives and dramatic stories. As examples of two important early filmmakers we examine the work of Edwin Porter from the USA and George Méliès from France.

In the last part of this chapter we analyze the foundations of the film industry in India. Even as a colony of Great Britain, natives of India fashioned their own films often based on mythical dramas. They were not aimed for export, but for distribution to their own people.

Early films were distributed around the world. Before World War I (1914–1918) films were traded on the open market by the foot or meter.

The First World War – in its time called the Great War – started in 1914 and ended in 1918. It involved many of the great powers: Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and Turkey called the Centralists; and France, Great Britain, Russia, Japan, Italy, US, Serbia, Montenegro, Belgium, Romania, Portugal, Greece and others called the Allies. Modern war techniques caused an unprecedented number of deaths (estimates run between 10,000,000 and 15,000,000) and casualties (more than 20,000,000). Another “novelty” was the use of propaganda to engage the heart and minds of the people.

The French company Pathé provided a model for film distribution by sending representatives to sell equipment and films where none existed. But Pathé lost its advantage due to the First World War, and thereafter Hollywood – led by Adolph Zukor – began its takeover of the world market.

In the beginning, the movies were simply just another technological marvel. Through the decade of the 1890s into the early days of the twentieth century, inventors worked with the first filmmakers and exhibitors to convince a skeptical public to attend a show with movies. In the process these inventor/entrepreneurs set the stage for a social, economic, and cultural change which would fundamentally alter the world.

To study the introduction of this new technology, one must acknowledge that the movies became a business in which inventors became entrepreneurs to make money with their new inventions in the USA. But inventors did not operate in a vacuum during the last decade of the nineteenth century, seeking to create some ideal new enterprise. Rather, they sought to sell their discoveries to some existing entertainment industry, be it vaudeville, theater, or the phonograph model.

Phonograph means literally sound (phono) writer (graph). In 1877 Thomas Edison invented the first phonograph that could record and play back sound. Initially, it was used in offices as a kind of mechanical secretary but soon it became used in many other ways, including talking dolls, music recordings, speech recordings, accompaniment of magic lantern shows and early movies.

First, the necessary new apparatus had to be created. For cinema this meant a camera to record images, and a printer to transfer them to the film strip. (Once vaudeville and theater proved to be the most popular models, a projector was needed to show movies to large groups of people.) In the beginning, Edison created a peep-show apparatus where one person paid to watch a film; but he abandoned this quickly for a theatrical audience business model.

There is no law which dictates that necessary inventions need to be restricted to just one purpose. Many times people create new knowledge for one goal, and then it becomes used for quite another; for example, computers in the 1960s did only calculations but by the 1990s computers were used primarily for writing. And frequently entrepreneurs do not recognize the range of purposes even once the new invention is available (for example, wide-screen movies were available decades before they became commonplace in the 1950s).

Wide-screen refers to the format of the film strip, the so-called “aspect ratio” meaning the relation between the height and the length of one frame. The standard aspect ratio is 1.33:1. When the aspect ratio is higher than 1.33:1 it is called wide-screen.

A second step occurs when this apparatus is taken to the marketplace, that is, it is innovated. For the movies this meant a set of marketing strategies by which to convince the public to part with its money.

Risk and timing weigh heavily on the prospective innovator. Will waiting help? Should one try to be first or learn from the mistakes of others? What will potential competitors do? The process of innovation is one of juggling new information with projected and real costs, with the demands of the potential audience. It took time to find ways to use the new motion pictures at low enough costs to please audiences of the day.

Finally, once the innovation has been established, it takes time to convince the rest of the world to adopt it. Indeed, it took more than ten years for cinema to become a mass leisure time activity. Many would try, but not until the 1910s would Hollywood convince the world that cinema could become a mass art form, not simply a passing fad. The diffusion of the technology was accomplished when the movies became an industry of influential, profitable enterprises.

This chapter charts the invention, innovation, and diffusion of the movies – starting with its predecessor the magic lantern in the late nineteenth century. The magic lantern was the precursor to motion pictures and showed how entrepreneurs brought the new movie-making and exhibition technology to a mass audience.

LEADING UP TO MOTION PICTURES: THE MAGIC LANTERN

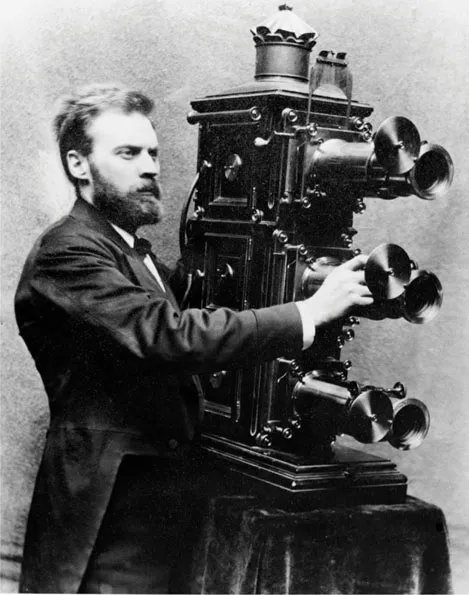

1.2 Magic lantern.

Motion pictures did not just start one day. Long before it was possible to let pictures move, people tried to create the illusion of movement. This proved possible with slide shows created by magic lanterns – functioning as early slide projectors. During the nineteenth century, magic lantern shows entertained people at gatherings as entrepreneurs sought to entertain groups with images of the far-away world. This was considered a technological marvel.

The development of the magic lantern started in Europe in the seventeenth century as oil lamps lighted up glass on which images had been drawn and then were beamed onto white walls. Several magic lanterns could be used at the same time to smooth the transition from one slide to another and made crude motion seem possible. Around 1850 projectors were made with two or even three lenses above each other to create this effect. The slides were painted or etched and were very sophisticated and colorful.

Magic lantern exhibitors traveled the world, but in the late nineteenth century Europe was the center of this form of entertainment. Behind a large screen several people (known as lanternists) would change the slides and move the lanterns. (When moving towards the screen an object seemed to come closer to the public so the illusion of movement was created.) Around 1840 photographic images were innovated into magic lantern shows. These photographic images proved much more realistic than their painted predecessors. It now was possible to capture and show a landscape of a foreign country or a far-away city. Illustrated lectures on travels became very popular.

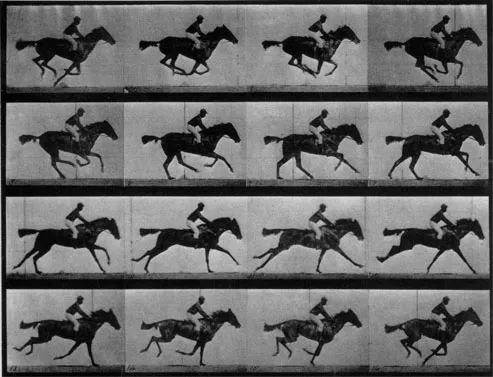

The level of sophistication of the theatrical magic lantern shows pushed the level of the illusion of movement. American photographers and lanternists took – and later projected – photographs of actors and actresses rapidly taken one after the other. In 1861 Coleman Sellers patented a special magic lantern called the kinematoscope. In the late 1870s Eadweard Muybridge, an American photographer, succeeded in making a series of photographs that captured the movement of horses. He did this with a battery of cameras activated by threads to trip the shutters stretched across the track, coupled with a neutral white background. Each camera captured part of the galloping movement; placing them one after another showed how the horse galloped.

The kinematoscope showed movement through a succession of images shown as a recurring series in a drum-like instrument. It was never marketed commercially but the technique was used in further experiments with moving images.

1.3 The Horse in Motion, Eadweard Muybridge, 1878.

But still these were individual images, so in 1882, when Frenchman Etienne-Jules Marey invented a camera that recorded 12 separate images on the edge of a revolving disc of film he seemed to have made a major breakthrough. Six years later he built the first camera to use a long strip of flexible film, this time on a paper base. By 1889 the pioneering photography company in the USA, Eastman Kodak of Rochester, New York, introduced a flexible film base for photography. This malleable base allowed the creation of a lengthy continuous set of frames and recording motion became possible. This would be the basis for the movie camera and projector.

With this base, scientists began to work to invent movie cameras and projectors: Thomas Edison and Thomas Armat in the USA; Etienne-Jules Marey, Louis Le Prince, and Louis and Auguste Lumière in France; Ottomar Anschutz, Max Skladanowsky and Oskar Messter in Germany; and William Friese-Greene and Robert Paul in Great Britain.

Two inventors sought to market this new technology and proved so successful that in time they spread their movie cameras and projectors around the world: Thomas Edison of the USA, and the brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière of France.

THOMAS ALVA EDISON: US INVENTOR

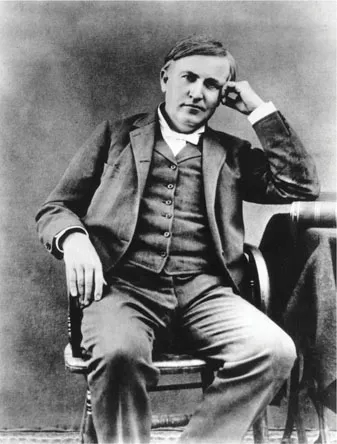

1.4 Thomas Edison.

Through the latter half of the nineteenth century the famous US inventor Thomas Edison sought to invent a movie camera – just one of a number of inventions. Edison’s success in creating recordings of movement was analogous to his creation of the phonograph to record sounds. Instead of the office tool Edison envisioned, the phonograph became used to record and play back music. Edison thought his moving pictures would become primarily tools for scientists, but instead his inventions became the movies for mass entertainment.

So Thomas Edison – in his large complex for inventions in New Jersey, assigned William K. L. Dickson to seek a commercial use for a “phonograph of moving images.” A breakthrough came after Edison met the Frenchman Etienne-Jules Marey – in Paris – who was working on a continuous photographic film strip. Edison saw the possibilities of this system and in October 1890 Dickson started working on an apparatus that functioned as a film strip to record moving images – a movie camera.

George Eastman’s development of the celluloid-based photographic film provided Dickson with new possibilities and on 20 May 1891 the first kinetoscope was demonstrated.

George Eastman (1854–1932) was the founder of the Eastman Kodak Company and the inventor of roll film. As an amateur photographer, Eastman b...