![]()

Section IV

POSTPRODUCTION

One writer/producer I know loves every part of production except the last step: saying the film is done. He’d rather tweak edits and the track endlessly in postproduction, in search of absolute perfection. His clients and investors won’t wait that long. He once told me, “A movie is never finished. It’s just taken away.”

This last section of the book is about getting the best audio in the least amount of postproduction time, so you can use whatever’s left—before they take the project away—for additional creative tweaking.

The whole idea of “postproduction” originated in the glory days of Hollywood, where tasks were broken up so studios could crank out dozens of films simultaneously. Films were shot—that’s production—and then edited and mixed in postproduction; then they were released from the assembly line.

These days post is anything you do after you’ve struck the set. It may include insert shots, new recording, computer-generated images, and a lot of other content creation. For some documentaries and commercials, the whole project is done with stock footage and computer graphics, so there’s no production … only postproduction.

For many projects—and most feature films—postproduction consumes the most time, and it’s usually the last chance for the filmmaker to exercise control. That’s certainly true of the track: during production, it’s hard enough just to capture intelligible dialog. Post is where you make that dialog sound natural, add the rest of the movie’s environment, and put in the score.

This section includes chapters on the overall postproduction sequence, the hardware it needs, and the actual techniques involved for every step from digitizing to the final mix.

Postproduction Workflow

• Editing should be creative, and that’s harder if the technology gets in your way. Understanding your technical options means you can control them better … and be more creative.

• Specialized audio software can do a lot more for your track than any audio functions in an NLE. This includes some important functions you might not be aware of.

• There are a lot of little steps necessary to build a good film. Doing them in the right order will save money and improve your track.

ORGANIZING AND KEEPING TRACK OF AUDIO IN AN NLE

Very few films are edited “in the camera,” taking shots that are just the right length and in the right order. There are a few kinds of video—such as legal depositions—that are shot in one continuous take with no editing at all. But every other project requires picture editing and soundtrack tweaking, and most of them involve quite a lot of it. When you have a good overview of this process, you can do it more efficiently.

Linear and nonlinear editing

The world is linear. Noon always comes one minute after 11:59 am. Productions are linear as well. Even interactive websites and menu-driven DVDs are built out of essentially linear sequences. Humans can’t handle nonlinear time, so the very idea of nonlinear editing is an oxymoron.

The terms “linear” and “nonlinear” have nothing to do with whether a production is analog or digital. It refers to the timeline that a production is built on, and how much control we have over it. A few kinds of productions are handled better in a linear environment; most in nonlinear style. The decision of which to use has important implications for how sound is handled.

Linear editing

Linear editing was the standard for videotape production, until computers made it possible to edit full-resolution video on a hard drive.1 In linear editing, the timeline is the master tape. Edits are made by playing precise sections of the original camera tape, while recording their picture in the right place on the master.

The timeline itself can’t change: stuff at the two-minute mark always comes exactly one minute after the one-minute mark. (In nonlinear, you can pick up a sequence starting at 2:00, move it much later in the film, and make what was at 3:00 now happen at 2:00.) You can copy or erase things from the timeline and replace them with other shots from camera tapes, but you can’t move pieces of the timeline itself.

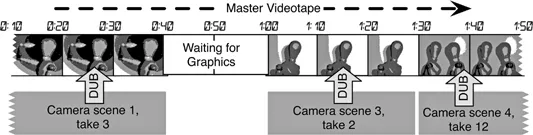

Think of the images along the top of Figure 10.1 as the master tape, running from ten seconds to one minute, 50 seconds. We’ve copied a few scenes from the original location tapes along the bottom. We also left a space for a graphic title, between 40 seconds and one minute; we’ll dub that when we get the title tape from the artist.

Figure 10.1 Linear editing: The show is assembled by dubbing scenes onto videotape … or by leaving precisely timed spaces where other scenes can be inserted.

We can build a whole show this way … and about for about 30 years that’s exactly how we did, from the very first 2” black-and-white quad tapes2 until computers got powerful enough to replace the process in the late 1990s.

The problem is that once something is on a linear timeline, it can’t be moved. You can erase or record over a scene, but you can’t nudge it a couple of frames without re-recording it. If everything in a show is perfect except the third shot is four frames too long, you can’t cut out just those frames. You have to re-record the next shot four frames earlier, and—unless you care to lengthen something—you also have to rerecord everything after it.

Analog audio for video was also usually linear. A timeline is one or two tracks on a multitrack tape, moving in lockstep with the video. Sounds are dubbed to the timeline from other tapes (or occasionally from other tracks on the same multitrack tape). Just like with linear video editing, you can dub to the timeline or erase pieces of it, but you can’t move pieces of the timeline itself.

Nonlinear editing

Nonlinear revolutionized video production, starting with low-res systems in the late 1980s, but added only one new concept: the ability to pick up and move whole pieces of previously assembled timeline. This was a crucial difference.

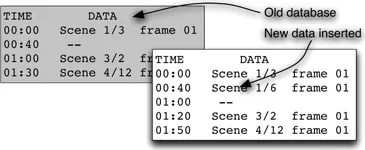

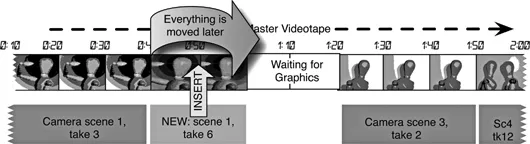

In a nonlinear editor (NLE), all of the images are stored in a computer. While there’s a timeline painted on the screen, the computer treats it like a database: an editable list that describes what part of the original scenes on its hard drive will be played back, and when they’ll be shown. If you move scenes around, the NLE merely rearranges the database and repaints the timeline (Figures 10.2 and 10.3). Video isn’t moved at all. Just a few bytes of data are involved, so it appears to happen instantly.

When the program is finished, complex effects are created by combining data from different places on the hard disk; then all the images are retrieved according to the database and either shown in real time and recorded to videotape, or rendered onto one large file.

The NLE’s internal databases can even be thought of as linear: when you insert or rearrange a scene, the system copies part of the data list from hard drive, rearranges it, and then “dubs” it back. When you ask an NLE to print out an EDL (Edit Decision List), it’s really just showing you a human-readable version of its internal database. There’s more about EDLs at the end of this chapter.

Figure 10.2 Nonlinear editing is really just database management …

Figure 10.3 … though the result appears to be edited picture.

Nonlinear audio editing works just about the same way, with databases—often, one for each track—relating to sounds stored on hard disk. The counting system is more sophisticated than SMTPE frames, since most good systems count individual audio samples (at least 48,000 per second for video soundtracks).

In an audio editing system, effects such as reverb or compression can either modify clips on the hard drive while you’re editing them, be noted with the clip for processing that clip during playback, or be noted for an entire track’s worth of clips.

Linear versus nonlinear for video editing

The primary advantages of old-fashioned linear video editing are speed and simplicity. There’s no time wasted on digitizing, file transfers, or rendering, so a long program with just a few edits can be put together in little more than the length of the show itself. The equipment is simple: all you need is one or more playback decks, a video recorder, and some way to control the decks and select the signal. The concept is even simpler—cue both decks and press Play on one...