![]()

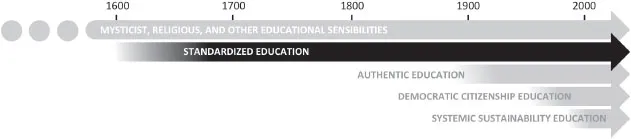

MOMENT 1 •

standardized education

In brief …

The term “Standardized Education” refers to those approaches to schooling that emphasize common programs of study, age-based grade levels, and uniform performance outcomes. The movement drew much of its inspiration and content from ancient traditions and religion, but its main influences have been industry and the physical sciences.

1.1 • The context …

The phenomenon of Standardized Education began to emerge in the 1700s and 1800s. Triggered by a cluster of entangled events – including the rise of modern science, industrialization, urbanization, and European expansionism – the need arose for a school system that could keep youth occupied and prepare them for the workforce.

1.2 • On knowledge and learning …

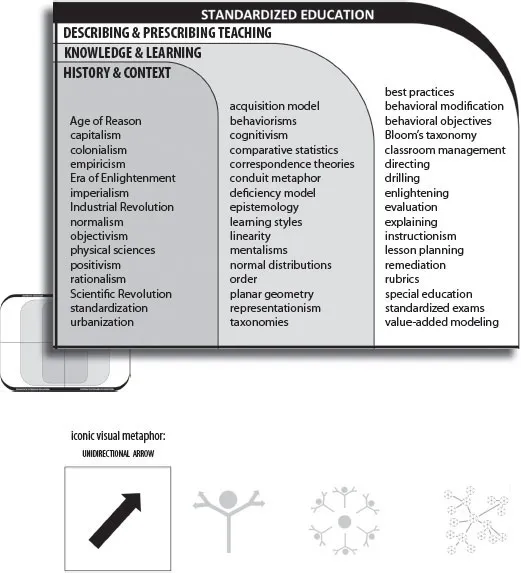

With the principal influences coming from the industry and the physical sciences, knowledge came to be viewed mainly in terms of COMMODITIES and OBJECTS. Learning, correspondingly, was framed as ACQUISITION and INTERNALIZATION.

1.3 • On teaching …

Teaching came to be understood in terms of DELIVERY and INSTRUCTION. Industry-influenced concerns with standards – with regard to quality control, efficiency, and so on – were imposed on both the expectations of students and the work of teachers.

Take a glimpse …

Suggested YouTube searches: [traditional schooling] [direct instruction] [classroom management] [back-to-basics education]

![]()

1.1 | The Emergence of Standardized Education |

We’ve just asserted that the notions of “teacher” and “teaching” are hotly contested.

Despite the great range of beliefs on these matters, however, some perspectives are encountered much more frequently than others. One in particular seems to prevail in the popular mindset, and it’s easily illustrated through an image search of the word teacher. We’ve just done exactly that, and the images below are reflective of the first five pictures that came up today:

This compiled image on this page is highly reflective of but not identical to the result of our Google Image search of teacher. To avoid copyright issues, the graphic was assembled from images provided courtesy of Thinkstock.com.

Of course, image searches aren’t exactly scientifically rigorous research exercises, but we believe this sort of result gives a few clues into popular assumptions on what teaching is all about – that is, in this case, that teaching typically involves standing in front of people with a view toward DEMONSTRATING, HIGHLIGHTING, TELLING, or otherwise DISSEMINATING knowledge. (Many other issues are presented in these images, but we’ll leave those for later chapters.)

As it turns out, that meaning has been particularly stable in English for many centuries. Indeed, it traces back at least to the origins of the word teach, which is derived from the Proto-Indo-European word deik-,“to show, point out.” It is also related to the Old English tacn, meaning “sign” or “mark,” and the root of the modern word token. The notion of teaching, that is, originally had to do with GESTURING TOWARD RELEVANT SIGNS, of ORIENTING ATTENTIONS TOWARD SIGNIFICANT FEATURES, of POINTING.

Given this history, it’s perhaps not surprising that the act of pointing is so prominent across the images above. Nor is it surprising that teaching has long been synonymous with DIRECTING, LEADING, and related notions. All of these terms share senses of orienting toward a common goal.

But the conception of teaching that is most commonsensical today involves much more than POINTING and DIRECTING. The task of the professional educator is framed by responsibilities for planning, measuring, and reporting in an outcomes-driven, evaluation-heavy, and accountability-laden culture of COMMAND-and-CONTROL teaching. A more complete sense of what’s being portrayed in images collected above is captured by such synonyms as DEMONSTRATE, INSTRUCT, TRAIN, ASSIGN, PRESCRIBE, PERSUADE, INFORM, EDIFY, SUPERVISE, INDOCTRINATE, and DISCIPLINE. These and other words were part of a convulsion of new terminology for teaching that occurred roughly 400 years ago. More broadly, this new vocabulary was part of an emergent conception of education as standardizable.

If we were pressed to choose an icon for Standardized Education, it would be the arrow. The image is implicit in some of the movement’s defining principles. Instances include …

… the belief that teaching causes learning, which is tied to a linear, cause effect sensibility … … the conception of progress through schooling, which is framed as incremental movement along a linear trajectory …

… notions of orders and hierarchies, which pervade disciplines, achievement levels, administrative structures …

The story of how the word standardized came to be so tightly coupled to education is an interesting and instructive one. Knowing a bit about it is useful for understanding some of the structures of contemporary schooling and some of the nuances of popular interpretations of teaching. Indeed, in many ways, the notion of standardizing is thoroughly represented in many of the images on the previous page.

Before going there, however, we invite you to think about the sorts of images and associations that you have for “standardized education.” What comes to mind?

Different people will answer in different ways, but our experience has been that some recollections are particularly popular. These include thoughts of standardized examinations, standardized (“common” or “core”) curricula, standardized lesson plans, and standardized classroom formats. More subtly, the idea shows up in standards of student behavior, professional standards for teachers, and the many, many documents bearing the word Standards put out by teachers’ organizations, ministries of education, and groups of concerned citizens.

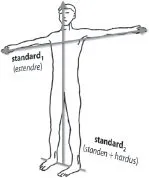

The word standard has many definitions, but they cluster around notions of authority, commonality, normality, and acceptability.

Its roots are contested, with two major theories. One traces standard to the Old French estendre, “to stretch out” (linked to the English extend), which is likely the sense that came to be associated with standardized measures. A second etymology links standard to the Gothic standan + hardus, “to stand hard,” suggesting senses of vertical uprightness and rallying point (as in a military standard).

These elements certainly resonate with us. For our own part, however, the most salient details summoned by the phrase “standardized education” are the aspects of formal education that are typically represented using points, lines, and rectangles – of, for example, bulleted lists of learning objectives, linear trajectories through lessons, or the rectangular schedule pasted on the corner of a rectangular desk organized in a rectangular array with other desks in a rectangular room along a rectangular hall in a rectangular school on a rectangular city block in a rectangulated city.

There is an implicit geometry here. We delve into some of its qualities in Chapter 1.2, insofar as it relates to the structures associated with modern schools and theories and metaphors used to describe knowledge and learning. For now, though, the goal is to offer a partial answer to the questions of how, when, and where the prevailing model of education as a standardized endeavor arose.

Ancient forerunners of the modern school

In a sense, it’s ridiculous to talk about the beginnings of education. Humanity is a teaching species; the practice of deliberately passing accumulated knowledge from one generation to the next extends much further back than any historical account.

However, it’s a different story with the matter of formal education – that is, with those social institutions designed to gather and disseminate insights through enrolling and teaching a body of students. There are some reasonably clear records on when these practices began to appear. In particular, across cultures, one of the major precursors of formal educational systems was the development of some form of writing – a technology that made it possible for groups of people to record and store their knowledge in a new and powerful way. In a sense, the invention of systems of writing compelled the invention of formal education – for two reasons. Firstly, mastering the skill of writing is cognitively demanding, requiring consistent instruction and persistent practice that can only be ensured through a formal setting. Secondly, as writing advanced and texts of knowledge accumulated, needs arose for strategies to preserve and disseminate that knowledge – means that were more consistent, accessible, and reliable than those that relied on families, clans, gilds, or religious orders. Those needs, in turn, spurred the education of small armies of scribes and record keepers.

It is thus that the first formal educational institutions appeared in ancient Egypt in the 3rd millennium BCE, and in China, the Indian Subcontinent, the Middle East, northern Africa, and southern Europe in the 2nd millennium BCE. For the most part, these ancient institutions likely bore little resemblance to modern schools. Nevertheless, their influence is still disc...