![]()

Part I

Primary Research and Rhetorical Tools

![]()

Introduction to Primary Research | 1 |

Figure 1.1 Primary research

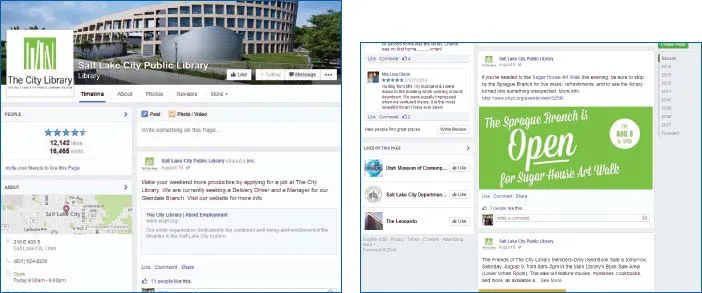

What comes to mind when you see the word cloud in Figure 1.1? We created this visual representation of primary research to introduce archival materials useful for investigating an issue or answering a research question. Facebook pages are familiar representations of how we use archival materials to represent ourselves to friends and family members. The compilation of pictures, links, slogans, bumper stickers, “about me” lists, likes and dislikes on our walls represent the profile we wish to create. Likewise, the screenshots in Figure 1.2 from the popular Salt Lake City Public Library Community Page illustrate how a community page captures the tone and content of a personal page in order to connect with group members on a more familiar and personal level.

The enormous popularity of Pinterest offers another illustration of the ways archival materials can be assembled and annotated to create a portrayal of the pinner. These digital spaces archive photos, music, comments, recipes, videos, posters, and stories of interest to you and the people or communities who “follow” or “friend” you. What information do you “Pin” or “Post” to your Facebook wall or Twitter account? If you don’t have a Facebook page or a Twitter or Pinterest account, what digital tools do you use to organize online content or communicate with others in your personal and professional communities? These online archives are composed of primary data; however, many people think of archives as only old documents stored in attics or cold manuscript libraries. Sometimes that is exactly what archives are, but more often than not you can find original collections of primary materials and artifacts online, in your mother’s bookshelf, in your closet, and in storehouses (both physical and digital) at work. In many cases, primary research may not yet exist; the researcher must generate information about a subject or community through a variety of collection methods such as surveys, interviews, and observation.

Figure 1.2 These screenshots were taken from the very popular Salt Lake City Public Library Facebook Community Page. You can see that the “wall” includes links to photographs, videos, events, and other information related to the community of Salt Lake City.

Source: Salt Lake City Public Library

Contemporary scholars think of archives as any primary material that might serve as either inspiration for research and writing or evidence in support of a theory or line of inquiry. More importantly, primary materials can help us understand individual communities and rhetorical actions aimed at a particular group of people. By examining and conducting original or primary research, rather than piecing together the ideas of others, researchers can create new interpretations and solutions and join their voices with other thinkers, activists, and performers.

What defines primary documents or archives for students? One student, Basil Paul, explains primary research this way: “Archives in my mind are no longer defined as dusty old boxes (although some of those do contain really cool things as I’ve learned in the class) but rather as muses. I can draw inspiration from a memo at work as I write about the culture that produced it. Or I can see a different perspective of a local neighborhood playground depending on the time of day.” We very much like Basil’s characterization of archives as “muses”—inspiration for finding a topic, an angle to explore, a way to put our personal mark on the subject. Let’s be honest, however. Yes, it’s interesting and fun to take control of your writing, to be in the driver’s seat when it comes to selecting a topic, establishing your own lens for viewing the material, and making it personal for both yourself and your intended audience, but those tasks are a bit more daunting than having someone assign you a topic, tell you exactly what to do, and return the writing back to you with a grade. Lauriel Paylor, another student, says, “It’s not every day that you walk into a classroom and you’re asked to guide your own learning experience.” Although many of our students are at first dubious and even a bit mistrustful sometimes of what we’re asking them to do, most of them in the end agree with Lauriel: “Having the opportunity to put into practice the things we [are] learning [is] both practical and interesting.”

Getting started is especially challenging when approaching a new task, particularly a writing project, so we will start with the basics. In this chapter, we will define our uses of the term “primary research” and contrast that act with secondary investigation, introduce common categories and locations of primary materials, highlight the specific role and responsibilities of the researcher in primary research, and introduce you to strategies for finding/developing a primary topic to investigate—strategies that we will explore in depth in later chapters of this text. We conclude our discussion here with a “peer-to-peer sharing” bibliography of information about primary materials. These entries are collected and annotated by our students and indicate the range of materials that might be considered primary.

Defining Primary Research

How do we define “primary” materials in order to begin understanding the kind of research methods that this book advocates? Some definitions of the term suggest that a primary source or archive is a physical or virtual place, a repository for locating information. Other definitions stress the historical nature of an archive, a collection of things from the past—and still others focus on the rare value associated with an archive. We think of primary collections in much broader terms, as collections of materials (or even single artifacts) that serve as inspiration and support for writing. In addition, primary materials often can help tell a story or document a past or current act, place, movement, culture, or community. As one of our students states, “[Through this kind of writing,] I learned how to use my own research, observations, and data to support claims. I learned how to create a style of my own instead of piecing together the findings of other scholars and adding a sentence or two.”

Writing with primary materials can:

1. Provide inspiration for choosing a topic that interests you.

Our students have examined local library collections to find inspiration, including: Southern Labor Archives, a movie poster collection from the 1950s, a collection of primitive surgical tools, a cookbook archive, and blueprints for public buildings.

2. Inform understanding and explain situations or circumstances.

One of our students conducted interviews and onsite observations to determine the differences in ways men and women behave at the gym. We have included his research in a later chapter.

3. Offer an alternative reading of an event.

Occupy Wall Street received extensive news coverage, but interviews with participants, police officers, and local residents reveal alternative views of the events.

4. Generate knowledge about a specific person’s influence or a community movement. An extensive collection of community cookbooks provided one of our students with the means to investigate the roles Junior League organizations play in different geographical regions of the country.

5. Recover people, events, artifacts, or actions in the past that might have gone unnoticed. One of our students came across a collection of cigarette cards. Neither of us knew anything about this artifact until our student provided a background story to explain the historical significance of these cards.

6. Revise a common story given new primary materials.

Another student garnered new information about the famous writer Alice Walker by interviewing Walker’s high school classmates and reading unpublished hometown stories written by one of Walker’s contemporaries.

7. Suggest an alternative solution to an existing problem.

A recent campus magazine article highlighted a group of our students’ work within a local prison initiative. The students interviewed inmates and based on what they learned about the institution’s past practices and inmates’ desires, the students designed an improved teaching curriculum and tutoring schedule for the inmates.

Most importantly, writing with primary materials ensures that writing is original and contributes to ongoing conversations.

Susan Thomas, librarian at the Borough of Manhattan Community College/City University of New York, created Table 1.1 to explain and illustrate the differences between primary and secondary research within the disciplines.

Table 1.1 Primary vs. Secondary Sources

| Humanities | Sciences |

Primary Source | • Original, first-hand account of an event or time period • Usually written or made during or close to the event or time period • Original, creative writing or works of art • Factual, not interpretive | • Report of scientific discoveries • Results of experiments • Results of clinical trials • Social and political science research results • Factual, not interpretive |

Secondary Source | • Analyzes and interprets primary sources • Second-hand account of a historical event • Interprets creative work | • Analyzes and interprets research results • Analyzes and interprets scientific discoveries |

Primary Sources | • Diaries, journals, and letters • Newspaper and magazine articles (factual accounts) • Government records (census, marriage, military) • Photographs, maps, postcards, posters • Recorded or transcribed speeches • Interviews with participants or witnesses (e.g., the Civil Rights Movement) • Interviews with people who lived during a particular time (e.g., genocide in Rwanda) • Songs, plays, novels, stories • Paintings, drawings, and sculptures | • Published results of research stud... |