An Introduction to Sustainability

Environmental, Social and Personal Perspectives

Martin Mulligan

- 338 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

An Introduction to Sustainability

Environmental, Social and Personal Perspectives

Martin Mulligan

Über dieses Buch

An Introduction to Sustainability provides students with a comprehensive overview of the key concepts and ideas which are encompassed within the growing field of sustainability.

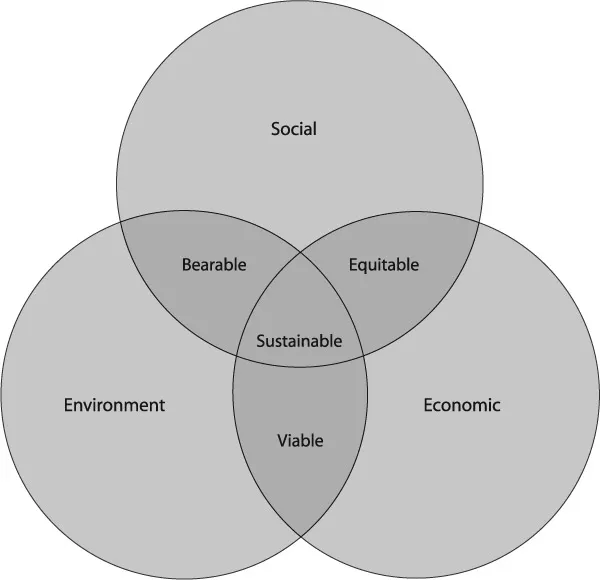

The fully updated second edition, including new figures and images, teases out the diverse but intersecting domains of sustainability and emphasises strategies for action. Aimed at those studying the subject for the first time, it is unique in giving students from different disciplinary backgrounds a coherent framework and set of core principles for applying broad sustainability principles within their own personal and professional lives. These include: working to improve equality within and across generations; moving from consumerism to quality of life goals; and respecting diversity in both nature and culture.

Areas of emerging importance such as the economics of prosperity and wellbeing stand alongside core topics including:

· Energy and society

· Consumption and consumerism

· Risk and resilience

· Waste, water and land.

Key challenges and applications are explored through international case studies, and each chapter includes a thematic essay drawing on diverse literature to provide an integrated introduction to fundamental issues.

Housed on the Routledge Sustainability Hub, the book's companion website contains a range of features to engage students with the interdisciplinary nature of sustainability. Together these resources provide a wealth of material for learning, teaching and researching the topic of sustainability.

This textbook is an essential companion to any sustainability course.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

Author’s Introduction

The Concept as we now know it

Arguments for Hope

To travel hopefully …

Successes and Failures Since 1987