![]()

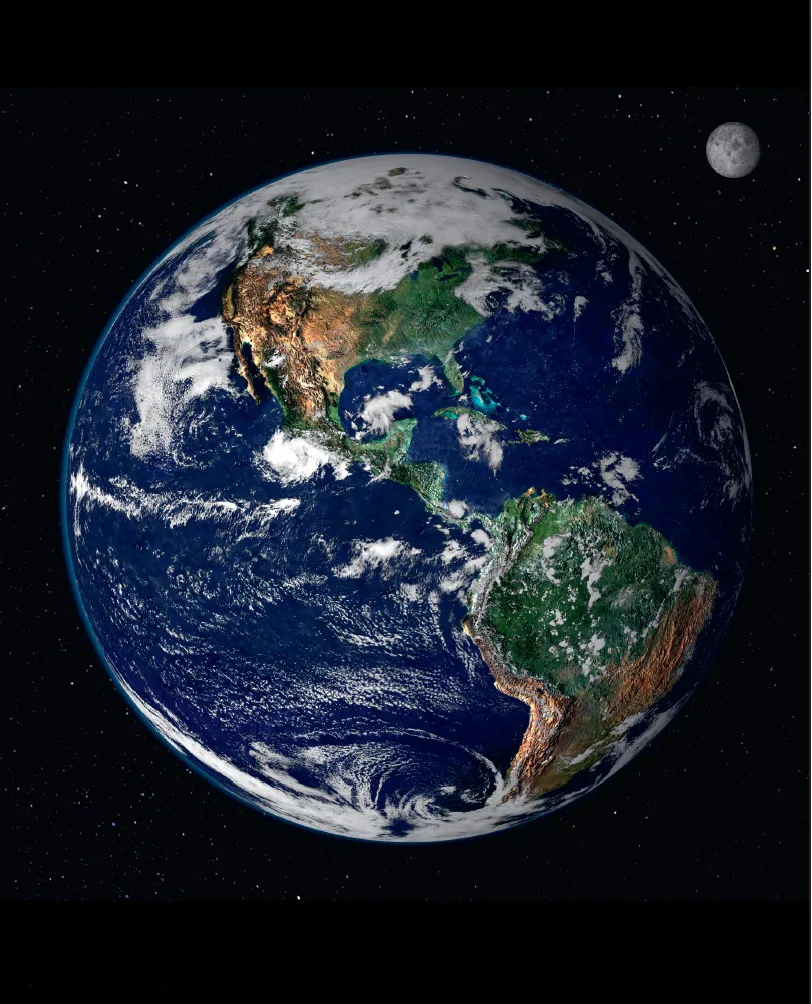

Reto Stöckli, Nazmi El Saleous, and Marit Jentoft-Nilsen, NASA GSFC

![]()

1

The Big Picture

The motivation to study environmental economics is all around you. Out a window you might see trees and grasses that require moderate temperatures and clean water to survive. Your body requires the same, as do the sources of the natural fibers in your clothing, the wood in your desk, the pages in this book, and the food you ate for breakfast. Even the oxygen you breathe comes from plants. It takes 300 to 400 plants of average size to produce enough oxygen to keep you alive. While the environment sustains your life, you enjoy manufactured goods, electricity, housing, and travel at the environment’s expense. Environmental economics is about making wise decisions about trade-offs such as these.

Natural resources are those components of nature that humans find useful. Some natural resources, such as trees and fish, can be harvested repeatedly with proper management. Others are available for extraction only once. The minerals used to make your cell phone, bicycle, and washing machine come from nonrenewable sources, as do the petroleum-based synthetics in your backpack and shoes. The tools of natural resource management address critical decisions of whether, when, and how to tap supplies of the Earth’s raw materi-als.

Economists use the goal of efficiency to guide decision-making. They ask the question: What would maximize the net benefit to society? Yet the cost-benefit comparisons that can lead to efficiency are often absent or flawed. Pollution costs seldom enter into private decisions about whether to drive another mile or build another factory. The benefits of habitat protection are often neglected in cost-benefit analyses of development projects. As a matter of law, the costs of implementing some environmental regulations are not weighed against the benefits. The opportunities to improve current approaches and the environment’s broad relevance to individuals, firms, and wildlife make the study of environmental economics and natural resource management important and exciting. This chapter highlights nine major issues to whet your appetite for the discussions that follow.

Market Failure: Can We Trust the Free Market?

In 1776, Scottish economist Adam Smith wrote that self-interested individuals operating in a free market could achieve efficiency as if guided by an “invisible hand.” Given these words from one of the founding fathers of economics, why would anyone want to meddle with the market? Unfortunately, as Smith himself seems to have understood, the conditions required for free-market efficiency are seldom fully met. This section introduces four reasons assistance from the not-so-invisible hands of policymakers is sometimes useful.

What you don’t know can hurt you.

When producers hold inside information about product-related dangers, consumers may overindulge in risky products. A lack of information can also lead consumers to under-consume products with unrecognized benefits. That’s why government agencies step in to require hazard-warning labels on insecticides and to teach consumers the benefits of eating vegetables. For such products, consumption closer to the efficient level can result from warnings, education programs, and other forms of information sharing that tend not to arise in a free market.

Competition underpins efficiency.

The European Commission fined computer-chip maker Qualcomm $1.18 billion for alleged anti-competitive actions and abuse of its market dominance. Why the large fine? Because a lack of competition generally leads to higher prices, lower quality, and smaller quantities. When barriers prevent competitors from entering a market, a small number of firms may become powerful and threaten efficiency. The challenge is for the government to limit market power while promoting innovation and permitting adequate incentives for entrepreneurs.

Side effects matter.

Externalities are effects felt beyond or “external to” the people causing the effects. When individuals decide how many cigarettes to smoke or how many trees to plant in their yard, they may not consider the costs or benefits conveyed on others. This common form of neglect results in too many purchases of goods like cigarettes that cause detrimental negative externalities, and too few purchases of goods like trees that generate beneficial positive externalities. The environment often bears the burden of inefficiencies that arise due to externalities. In this book you will learn how governments use taxes, subsidies, and property rights to address externality problems by helping people feel for themselves—or internalize— the effects of their own behavior.

Free riders cause the underprovision of public goods.

Public goods are goods whose benefits: (1) can be received by more than one person at a time; and, (2) cannot be kept from people who did not pay for them. Streetlights, TV signals, and military protection are classic examples. Public goods present problems because individuals can free-ride on the purchases of other people by receiving benefits from goods they did not pay for. As a result, too few public goods are purchased. Many goods and services related to the environment suffer from the same free-rider problem. Consider efforts to remove toxins from rivers and lakes. Large numbers of people benefit from these efforts, regardless of their personal contribution. Free riders would rather have someone else pay to make the water safe, so too few people pitch in for cleanups. In such cases, the government can tax beneficiaries and use the revenue to fund cleanups among other public goods. This textbook elaborates on the threats to free-market efficiency and explains the pros and cons of market intervention.

If someone pays to clean the water, everyone benefits. But who wants to be the one who pays?

Waste and Recycling: Where Can We Put It All?

People buy a lot of stuff, so sooner or later there’s a lot to throw away. In a typical year, the average child in Australia receives almost $500 worth of toys, and the average Canadian buys $3,400 worth of clothing. Worldwide, consumers purchase $260 billion worth of home furnishings and appliances each year. In many countries including the United States, the number of landfill disposal sites is decreasing while the volume of waste is increasing. As disposal sites near cities fill up, waste must be transported greater distances at a higher environmental cost. Beyond that are problems with groundwater contamination from landfills and ash toxicity from waste incineration.

Trash bins in Mexico guide users to sort organic and inorganic items as the first step in coping with large volumes of waste.

Approaches to growing waste problems include zero waste initiatives that encourage households and firms to imitate sustainable ecosystems in which discarded materials are converted into resources or energy for others to use. Some solutions come from firms, such as Nike’s use of more than 3 billion recycled plastic bottles to make soccer uniforms. Other solutions come from local governments. For instance, thousands of U.S. communities have adopted pay-as-you-throw programs that encourage waste reduction by having people pay by the bag for waste sent to the landfill. Chapter 9 explains more solutions to the mounting waste problem.

Sustainable Development: How Long Can This Last?

Before we decide how to dispose of things, we must decide how to make things. Some production processes can be continued long into the future; others cannot. We obtain most of our energy from nonrenewable oil and coal reserves. We use stocks of old growth forests, groundwater, and fertile topsoil at unsustainable rates. We send harmful emissions into the air and water faster than they can dissipate, so they collect and increase in concentration. The destructive path of most modern development has inspired attempts to alter that path. For example, the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) rating system provides guidelines for socially responsible building design and acknowledges developers who endeavor to protect the environment.

Recent innovations in industries that include forestry, mining, cement, transportation, and energy represent progress toward sustainability. But many questions complicate the issue: How much progress is enough? What value should we place on the welfare of others? Should we act, as philosopher John Rawls suggested, so that we would be indifferent between living now or in the future? Because behavior influences the well-being of future generations, we must decide the toll we will take on their quality of life.

Economists have developed ways to assess the values of animal species.

Biodiversity: What Is...