![]()

Part One

Forever Beholden

The State of Orphanhood

I am her father—though she is an orphan

Joseph Ibn Hasday, “Shirah Yetoma”

[A female orphan poem]1

![]()

Chapter One

Poetics of Orphanhood

When Dahlia Ravikovitch was six years old, her father was killed in a car accident—a traumatic event that would fundamentally orient her writing and play a central role in the way she established her poetic self. This incident and its repercussions, which scholars have described as “a fatal forcibleness”—a force that ties the speaker to her orphanhood1—appear in various guises throughout Ravikovitch’s work. Indeed, as Hannah Naveh suggests, for the speaker in Ravikovitch’s writings the work of mourning is an endless quest.2

In her first book of poetry, The Love of an Orange (1959), in an untitled poem beginning with the words “On the road at night” (Omed al hakhevish), Ravikovitch articulates this experience: veratziti lishol et haish ad matai chayevet ani/veyadaati zot merosh shetamid chayevet ani. In Chana and Ariel Bloch’s translation, these lines read: “And I want to ask the man how long will I have to./And I know, even as I ask, I will always have to.”3 The translation of the second line, however, does not capture its full meaning. I prefer to render it: “I always knew, I was forever beholden”—a statement that embodies Ravikovitch’s personal experiences and poetic commitments, as well as providing a prophetic definition of her writing as a whole. Although the line can be read in multiple contexts—ars poetica, femininity, nationality—one cannot ignore its original appearance in a section of the book primarily concerned with her father’s death. In this context, “I was forever beholden” becomes a poetic articulation of the nature of her trauma.

This early declaration reemerges almost four decades later, in the poem “There Is No Fear of God in This Place” (Ein yirat elohim bamakom hazeh). The father speaks to his daughter:

When I was run over and killed on that black road,

in an eyeblink, alone,

struck to the ground, startled and shamed,

in that eyeblink I knew:

In all the years to come

like me you’d remain startled,

(CP, 255; BK, 231)

First published in Nathan Zach’s periodical Hinneh in January 1995, this poem was republished a few months later in The Complete Poems So Far. There is, however, a significant difference between the two versions. Where the earlier reads, “instantaneously, I knew that until the end of your days/like me, you would be petrified,” the later poem has, “in that eyeblink I knew:/In all the years to come/like me you’d remain startled” (emphasis added). In her reassessment of the speaker’s orphanhood, the author ultimately decides on a period that goes beyond the speaker’s human limits; the second version resounds like an ancient curse, as though orphanhood is a state that will transcend the orphan’s own life time.

This chapter examines the psychological and poetic “curse” at the heart of Ravikovitch’s writings, in which traumatic loss creates an emotional mechanism of psychological imprisonment whereby the Ravikovitch speaker is condemned to an existence inescapably defined by orphanhood. Trauma, as Cathy Caruth explains, “is not experienced as a mere repression or defense, but as a temporal delay that carries the individual beyond the shock of the first moment. The trauma is a repeated suffering of the event, but it is also a continual leaving of its site.”4 By investigating these “repetitions” and “leavings of the site” in Ravikovitch’s work, I wish to explore the traumatic experience expressed in her writing and to focus on the specific poetic language and structure of its articulation.

A caveat: in pointing to the state of orphanhood as a key to understanding the Ravikovitch oeuvre, I do not claim it to be the only key. Moreover, the psychoanalytical arguments I make aim to illuminate Ravikovitch’s writing, not to make assumptions about her private life. Although Ravikovitch discussed some of her biographical experiences in interviews, this study is based only on her literary work. My aim is to identify a “poetics of orphanhood” and to explore the effects of bereavement within Ravikovitch’s poetics.

A Legacy of Psychosis

On the road at night there stands the man

who once upon a time was my father.

And I must come to the place where he stands

because I was his eldest daughter.

And night after night he stands alone on the road

and I must go down to that place and stand there.

And I want to ask the man how long will I have to.

And I know, even as I ask, I will always have to.

In the place where he stands there is a fear of danger

like the day he was walking along and a car ran him over.

And that’s how I knew him, and I found ways to remember

that this very man was once my father.

And he doesn’t tell me one word of love

though once upon a time he was my father.

And even though I was his eldest daughter

he cannot tell me one word of love.

(CP, 19; BB, 3; cf. BK 55)

This poem expresses and embodies a deep understanding of the speaker’s psychotic mechanism and obsessive behavior. The reader is informed that “in the place where he [the man, the father] stands”—that is, in the middle of the road—“there is a fear of danger.” By forcing “his eldest daughter” to stand with him in the same place night after night, the father puts her at risk too. In this sense, the poem does not deal simply with the trauma of the father’s death, but also with the state of perpetual psychotic risk in which the speaker lives: she cannot stop going “down to that place and stand[ing] there” night after night and, in so doing, exposing herself to the danger.

What’s more, the daughter does not really know her father. She has to mark him in order to recognize him: “And that’s how I knew him, and I found ways to remember/that this very man was once my father.” This is even more evident in Hebrew: shezeh haish atzmo hayah paam aba sheli/vehikarti oto venatati bo simanim (“and that’s how I knew him, and I made signs so that I could always recognize that this man was my father”). The expression natati bo simanim, literally “I gave him identifying signs,” alludes to a law discussed in Mishnah Baba metzia 2:5–7. According to this Talmudic discussion, a person son who loses something in the public domain must provide simanim, identifying signs, in order to reclaim it.5 But the only way in which the speaker can identify her father is through his crazy act of standing in the middle of the road in the dark. She can recognize him neither by his appearance nor by his voice. Rather, what enables her to recognize him is something she feels within herself, the notion that he has to take the risk (otherwise, he could have prevented his own death), and that she, likewise, has to follow. The father is thus the one in a position of power who forces the daughter into danger.

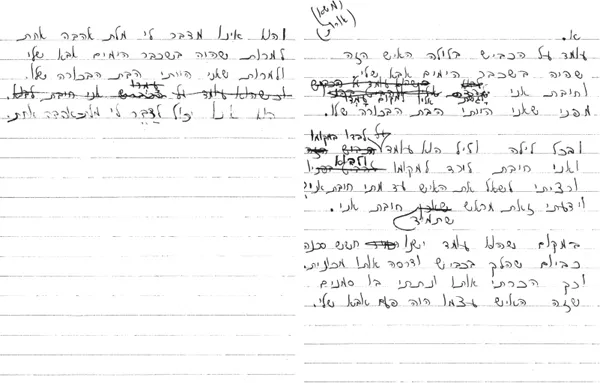

Manuscript of “On the road at night,” reproduced from Ravikovitch’s unpublished bequest by kind permission of Ido Kalir.

What stands at the center of the poem is not orphanhood per se, but the speaker’s psychosis, which she inherits from her dead father. If orphanhood plays a role here, it is in the etiological connection the speaker makes between her orphanhood and the risk of psychosis that lies constantly in wait for her. In this way, the poem is not “fantastic,” as it might appear at first glance. Rather, it is a poem of insight and self-analysis whose central image of standing in the road at night allows the speaker to investigate the origin of the power that repeatedly forces her to take a variety of psychotic risks.

Poetics of Trauma Symbolic Order and Repetition

One of the most notable elements of Ravikovitch’s “On the road at night” poem is its structure. On the surface, it seems to adhere to a strict (symbolic) order: it has four stanzas of four lines each, and it is syntactically conventional. The poem also suggests a standard causality: “And I must come to the place where he stands/because I was his eldest daughter…. And even though I was his eldest daughter/he cannot tell me one word of love.” At the same time, however, these features are entwined with a wild fantasy, one based on the irrational compulsion to visit the dead father “night after night.”

According to Jacques Lacan, the symbolic order is a structure encompassing human existence, the sociocultural world of language and signifiers. Entering into language and accepting the rules and dictates of society is a fundamental part of humanity’s social construction. Thus, the symbolic order is entwined with an acceptance of the Name-of-the-Father and its laws and restrictions, which contribute to the formation of both individuals and cultures.6 In other words, the symbolic order is the law (the father’s law), the hegemonic discourse, and everything within the confines of social censure. A movement of repetition and fixation, by contrast, arises from repressed desires, articulated in a metaphoric and metonymic language that does not yield to the rules of hegemonic censure. Accordingly, the repetition, fixation, and obsession expressed in Ravikovitch’s poem are traumatic features that disconnect the poem from the language of logic and its rules, even as the compulsive repetition is articulated by using the very conventions of the hegemonic discourse. The poem thus maintains the symbolic order in its structure and language, but its fixation on the dead father actually deviates from both social and psychological norms, thus undermining the symbolic order’s foundations.

A similar device is used in the poem “Clockwork Doll” (Bubah memukenet) to describe psychological collapse, a lack of control, and an attempt to escape estrangement:

CLOCKWORK DOLL

That night, I was a clockwork doll

and I whirled around, this way and that,

and I fell on my face and shattered to bits

and they tried to fix me with all their skill.

Then I was a proper doll once again

and I did what they told me, poised and polite.

But I was a doll of a different sort,

an injured twig that dangles from a stem.

And then I went to dance at the ball,

but they left me alone with the dogs and cats

though my steps were measured and rhythmical.

And I had blue eyes and golden hair

and a dress all the colors of garden flowers,

and a trimming of cherries on my straw hat.

(CP, 27; BB, 7; cf. BK 63)

The image of a clockwork doll that is broken and then fixed could refer to an emotional state, a gendered position, or to social estrangement. The poem presents a central tension between uncontrolled movement—“and I whirled around, this way and that” (in Hebrew: vepaniti yeminah usmolah, lekhol haavarim, literally “and I turned right and left, to all sides”)—and reasonable, obedient behavior, “and I did what they told me, poised and polite” (in Hebrew: vekhol minhagi hayah shakul vetzayyetani, literally “and my behavior was levelheaded and obedient”). In the emotional space created within this tension, the speaker expresses her wavering back and forth between different wishes, capacities, and attributes that contribute to her experience.

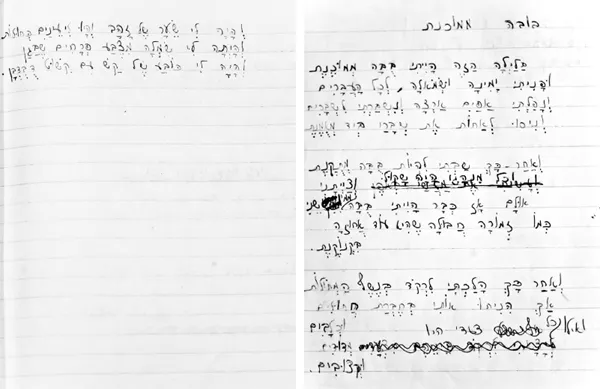

Manuscript of “Clockwork Doll,” reproduced from Ravikovitch’s unpublished bequest by kind permission of Ido Kalir.

The nature of the relationship between the traumatic event and the speaker’s behavior is not clear. Is it a poem about the taming of the shrew—a psychotic breach ultimately brought under control by hegemony—or does it describe a unique event in the speaker’s life, an event that by its very exceptionality in fact emphasizes her normative existence? Does the poem address an inherent gap between the speaker and her surroundings, or does it deal with the speaker’s difficulty in assimilating herself anew into a society to which she believes she belongs?

The sonnet-like form suggests an internalization of the symbolic order as well as the speaker’s consent to law. The poem articulates the heavy price paid by the subject for returning to normative behavior after the psychotic eruption, evident only in the description “and I whirled around, this way and that,/and I fell on my face and shattered to bits.” Silencing the uncontrolled breach—accepting the symbolic order—entails obedience, self-correction, and facing up to the failure of reassimilation. Such a reading of the poem assumes a disparity between the symbolic order, which enforces its norms, and a psychotic or deviant personality, for which whirling around (disrupting the symbolic order) is an “authentic” form of behavior.7

Another reading, however, reveals an alternative interpretation of the relations between self, psychotic breakdown, and symbolic order. The poem opens with the declaration that the events described occurred on a specific night (“that night,” balaylah hazeh, a phrase taken from the Passover Haggadah), when the speaker was a clockwork doll that whirled around until she fell and shattered to pieces. From this, one might infer that the speaker does not ordinarily resemble a clockwork doll, but is a woman fully aware and in control of her actions and their consequences, whose steps are “measured and rhythmical” (as they will be again later in the poem). Perhaps the breach did not stem from within her at all, but was caused by an aggressive and destructive activation of the doll. It is not the symbolic order but the crisis itself that has been forced upon her. She experiences and understands her psychosis not as an immanent part of her personality, but as an external force exerted upon her on a specific night.

There is another translation issue at stake here. Chana and Ariel Bloch render the third line of the second stanza “But I was a doll of a different sort.” In Hebrew, however, Ravikovitch writes: ulam az kevar hayiti bubah misug sheni, literally “But then I was a doll of a second sort,” a vernacular usage referring to something that is reduced, decreased, second-rate; “damaged goods,” to use the Chana Bloch and Chana Kronfeld translation.8 In essence, the doll is the same before and after the psychotic breach; afterwards, however, she is ridiculed and has declined in value. The poem thus traces not an inner transformation but an external crisis, which neither stems from the speaker’s personality nor changes it dramatically.

These two readings do not allow a clear-cut separation between external and internal experience, which are encountered simultaneously and alongside the subject’s awareness of her situation, establ...