CHAPTER 1

“With Fire and Dynamite”

As the blaring of the Bourbon trumpeters marching down the Gran Vía in Barcelona on September 24, 1893, faded into the shouts and vivas of the throngs of ebullient onlookers, General Arsenio Martínez Campos sat comfortably atop his steed reviewing an oncoming squadron of lancers. From the balconies above, heads tilted to get a glimpse of this unusual spectacle of military grandeur in celebration of the fiestas of the Virgin of Mercy.1 Martínez Campos later recounted, however, that at 12:30 p.m., merely a half hour into the day’s festivities, he was “contemplating with satisfaction the military spirit and good demeanor of our lancers, when at the instant they passed in front of me I was surprised by a very powerful detonation accompanied by a large cloud of smoke, running and shouting.” Since the general was “a little hard of hearing,” he assumed there had been an accidental artillery explosion, but instants later he heard, and felt, another blast that knocked him off his horse.2

Moments earlier, a municipal officer noticed a man push out of the crowd onto the street and advance toward Martínez Campos. While the officer “was asking himself what this subject was up to,” the man hurled two Orsini bombs at Martínez Campos. They exploded at the feet of his horse, mutilating the animal but only slightly injuring the general. Two nearby generals received minor contusions, but a civil guardsman had his leg blown off and died shortly thereafter. The bombing caused one death and sixteen injuries, some quite severe, such as that of a spectator who had her leg amputated.3

The explosions and screams triggered a wave of frenzied panic. “The multitude, crazy, blind, ran in opposite directions knocking over everything, falling here, smashing into benches, trees, clogging up doorways and stores forming legitimate human mountains.”4 “Some of the soldiers remained immobile and stupefied. Others broke formation as if they were ready to run. Others, here and there, as if ripped by panic, pointed their rifles at the people.”5 But rather than take advantage of the chaos to escape, right after the explosion the bomber threw his cap in the air, shouting, “¡Viva la anarquía!” and stood still as the police seized him.6 His name was Paulino Pallás Latorre, and he had just unleashed the first major atentado (attack) in a series of shootings, stabbings, and explosions that would earn Barcelona the reputation of “the city of bombs” over the next decade and a half.

As part I explores, however, bombings did not only occur in Barcelona. Both France and Spain experienced their own wave of assassinations and explosions in the early 1890s. With each new spectacle of dynamite, politicians and journalists across the political spectrum demonized anarchists as subhuman monsters who threatened to turn back the clock on the “progress” of “civilization” in accord with what I call “the ethics of modernity.” Media dehumanization paved the way for physical dehumanization as both states carried out mass arrests and passed harsh anti-anarchist legislation that expanded state repression well beyond anarchism. Such measures provoked little popular outcry. Yet whereas the French state would pull back on escalating repression by mid-decade, its Spanish counterpart would only escalate its brutality over the coming years, thereby provoking a ground-breaking transnational campaign against the “revival of the Inquisition.”

Not long after his arrest, the police, who previously knew nothing of Pallás, paid a visit to his cramped apartment in the working-class neighborhood of Sans outside of Barcelona. There they found his pregnant wife Àngela, their three young children, his widowed mother, and his fifteen-year-old brother living together in a “modest room.”7 His wife claimed that she knew nothing of the bombing; earlier that morning Pallás had left home simply telling her he would return later in the evening. According to his later testimony, Pallás went into Barcelona and ate a meal at a taverna near the Mercado de San Antonio before continuing up Montjuich mountain to a cave, where he dug up two bombs he had previously buried wrapped in cotton to protect them from the humidity. He claimed to have acquired the bombs from an Italian anarchist named Francesco Momo (a convenient story since Momo had accidentally blown himself up the previous March). After unearthing the small spherical explosives, Pallás wrapped them in handkerchiefs, rested them in his sash, and set off for the military parade.8

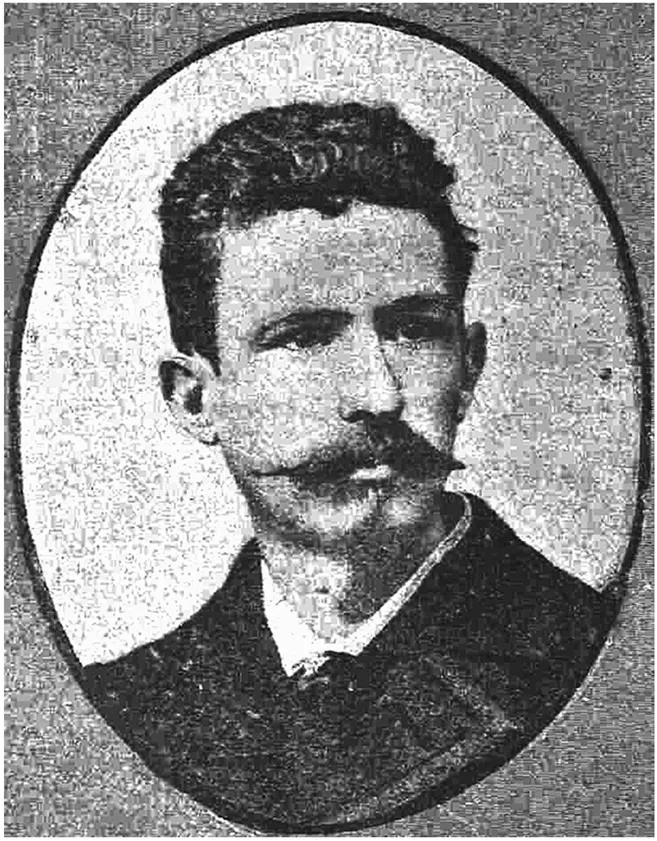

FIGURE 3. Paulino Pallás. La Campana de Gracia, September 30, 1893.

In the Pallás home, the police found a laminated lithograph portrait of the Haymarket martyrs, anarchist pamphlets and periodicals, and a copy of Kropotkin’s The Conquest of Bread.9 Pallás had wholeheartedly embraced anarchism, but he had only done so a few years earlier. The son of a stonecutter, Pallás was born in 1862 in Cambrils, a small coastal village outside of Tarragona. In his youth, he learned to be a typographer and lithographer, but he had trouble finding consistent work. To supplement his income, he sometimes sang in the choir that performed Els hugonots at the Liceo Theater on La Rambla in Barcelona. Considered to be generous and altruistic by those who knew him, Pallás was said to have adopted “authoritarian socialism” in the late 1880s before moving his family to Argentina to find employment.10 The Pallás family were among the nearly 1.5 million people who journeyed from Spain to the former colony of Argentina between 1871 and 1914.11

In Buenos Aires, and then Rosario de Santa Fe, Pallás immersed himself in the diverse, multilingual world of Argentine revolutionary politics, regularly attending discussion groups and increasingly making a name for himself as an orator at public events such as International Workers’ Day on May 1, 1890. He met the famed Italian anarchist Errico Malatesta, then living in Argentina, who influenced Pallás’s shift toward anarchist communism. Continually in search of work, the penniless Pallás traveled to São Paulo, an important hub for the nearly 200,000 Spaniards who migrated to Brazil from 1887 to 1903. There he sought work at a local Italian café frequented by Spaniards and Catalans, though to no avail. The following year the family relocated to Rio de Janeiro.12

Eventually Àngela had to return to Barcelona after receiving word of the passing of her father. Paulino followed her in the spring of 1892. With the inheritance from her deceased father, they opened a cloth shop before Pallás left the enterprise for more stable employment at a printing workshop, but he was fired for his political activities. He is then said to have spent some time in Paris, where he would have been influenced by the frenzy whipped up by the soon-to-be-legendary French anarchist bomber Ravachol (the subject of chapter 3), since, on his return in the fall of 1892, Pallás helped publish an anarchist periodical in Sabadell bearing his name (Ravachol).13 In the months leading up to the bombing, Paulino and Àngela seem to have spent most of their time working from home on their Singer sewing machines. Neighbors also explained to reporters that Pallás rarely spoke of politics and that his poor wife did not know he was an anarchist, something she even affirmed herself. However, she did in fact identify with anarchist ideas but most likely denied it out of fear.14

The day after the bombing, before there was time to clean up the hats, canes, umbrellas, and shredded fabric that still littered the intersection of Gran Vía and Muntaner, the journalistic panic and politicking had already begun.15 Politicians and commentators from across the political spectrum demanded that the government mete out harsh repression on the anarchists whose crimes were commonly described in the press as an affront to humanity that turned back the clock on civilization. The conservative La Época of Madrid wrote that anarchist violence “fills the country with great fear. . . that makes social life impossible, hoping to drag us back to a state of barbarism unimaginable even in primitive times.”16 In the Madrid liberal daily El Imparcial it was the “barbarous anarchists that are the shame of humanity.”17

The Liberal and Conservative Parties dominated Restoration Spain after the destruction of the short-lived First Republic in 1874. Though differences existed between the two parties, they prioritized the stability of the liberal monarchy against the ultramontane Carlists on the right and republicans and the workers’ movements on the left. Together they established the turno pacífico, a system to alternate in power every two years through electoral fraud perpetrated by local bosses called caciques who adjusted vote totals in exchange for political favors. This system would start to falter over the coming years as differences between the two parties expanded, but in 1893 Conservatives, Liberals, and even republicans called for the harsh repression of anarchists—though their arguments entailed very different political conclusions. The Conservative press argued that repression must target what they saw as the root of the threat: the uncontested spread of anarchist ideas and associations. The editors of La Época argued that there have always been those born with the criminal germ, but in the past they were “without mutual solidarity,” so their crimes were “hidden in shadow. . . . It was reserved for our century, this new. . . progress of criminality, as much in its methods as in its systematic organization.” The solution, therefore, was to crush the ability of those predisposed to crime to associate or propagate their ideas, but according to the editors:

Modern Governments have remained apathetic, conceding to theoretical anarchism the same prerogatives and liberties that the most noble and holy ideas deserve to enjoy. The result of this weak tolerance has been all of these horrors. . .. In the Spanish Parliament there has been no shortage of orators who have declared the legitimacy of anarchist ideas, as long as they remain purely in the realm of theory. “Liberty—they said—has a correction for its deviations in liberty itself ”; and armed with the phrase. . . they thought they had resolved the dreadful problem [of the anarchists]. The recent events of Paris, Madrid, and Barcelona have been necessary to prove the ridiculous nature of such garrulous language. . .. Today all tolerance of the anarchists should be gravely censured. . .. It is necessary, in addition, to persecute without rest and without compassion those who espouse anarchist ideas. Their secret sessions, their meetings, their periodicals, their libels are outside of the law.18

Conservative critics considered the Gran Vía bombing to be definitive proof that Liberal tolerance for free speech inevitably ended with carnage. Like the anarchists themselves, ironically enough, Conservatives argued that even theoretical anarchist ideas would over time catalyze social upheaval. Social defense, they claimed, required the government to jettison its liberal commitment to civil liberties and distinguish between constructive and destructive ideas. The Liberal Party mouthpiece, El Imparcial, cautioned against repressive laws: “If there are police deficiencies in Barcelona then this is something that should be disclosed to the ministro de la Gobernación with the governor of Barcelona, but to hope to charge liberal methods with the blame for these crimes which are committed under all governments, and one could even add with more frequency when the means of command are tighter, is to hope for the impossible, because it would be the same as hoping that a few coercive laws would cure what an absolutist government and a real police army in Russia haven’t been able to cure.” If the methods of czarism, the most repressive government on the continent, actually augmented bombings and assassinations, the Liberals argued, then abandoning civil liberties and shutting down newspapers would risk exacerbating the problem. Simply enhancing repression at the expense of liberties would not work, but, as El Imparcial was quick to point out, neither would turning in the other direction toward a republic since anarchist violence was “a social form from which neither monarchies nor republics are exempt.”19 In response, the republican El País claimed that anarchist violence would disappear under a republic: “The republicans would make the ferocious intransigence of anarchism useless from the moment they facilitate a legal path for the rational just demands of the working classes. If the Republic translated into laws all or the greater part of the aspirations of the workers. . . what purpose would dynamite bombs have anymore? The Republic isn’t only law and justice. The Republic is peace.”20 The only way to stop more bombs from exploding, the republicans argued, was to resolve the social issues that turned poor people into enemies of the state. They promised that a future republic would be up to the task. Conveniently, they ignored the prickly problem of explaining why the French Third Republic was struggling through its own wave of propaganda by the deed.

Regardless of public debate over the proper response to the bombing, the police wasted no time in rounding up between eleven and twenty suspected accomplices the next day, before reaching sixty arrests shortly thereafter.21 Inspector Tressols and his agents targeted labor leaders, “s...