![]()

Part I

ECONOMIC EFFICIENCY AND THE ROLE OF GOVERNMENT

![]()

1.

INCOME EQUALITY:

THE EARLIEST STANDARD OF EFFICIENCY

The search for a definition of economic efficiency began with the emergence of democracy. With democracy came, for the first time in history, the need to ask explicitly whom government should serve. Kings were never bothered by this question. “L’état, c’est moi,” Louis XIV of France declared in the early eighteenth century. But who should a government “of the people” and “for the people” serve, when some of the people are rich and some are poor?

In 1793 the French “people” executed Louis XVI and proceeded to ratify in a referendum a constitution that guaranteed income redistribution in the form of public relief and public schooling. (“People” is in quotation marks because not all the French wanted the king executed, nor did all of them vote for the constitution.) But how much should be redistributed? The constitution of 1793 did not say, and the political process that would have determined it was thwarted before it started. A group of citizens, “The Conspiracy of Equals,” demanded that the constitution be implemented, but the group was disbanded when its leader, François Noël Babeuf, was sent to the guillotine. The question was addressed theoretically, however, by a contemporary of Babeuf, the wealthy British philosopher Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832).

Bentham based his theory of the efficient degree of redistribution on three building blocks: (i) the happiness of a society consists of the sum of the happiness of each of its members, (ii) an efficient allocation of resources is one that maximizes the happiness of society, and (iii) the happiness that a person gets from an additional dollar (English pound) decreases as the number of dollars that person has increases. In the language of economics, “happiness” has long since been replaced by “utility,” and Bentham’s theory is known, therefore, as Utilitarianism.

Utility, U, is made of tiny units called “utils.” Utils are derived from money. Each additional dollar buys additional utils, and the number of utils that each additional dollar buys is called “the marginal utility of money.” The relationship between U and a person’s income, I, is shown in figure 1.1. The marginal utility of money is denoted in the figure by ∆U. More income yields more utility, but the relationship is not linear: while an extra dollar always brings additional utility, this additional utility gets smaller as a person’s income increases. In other words, the marginal utility of money, ∆U, decreases with the amount of money a person has.

FIGURE 1.1: THE UTILITY FUNCTION

A rich person is higher on the utility function than a poor person. Therefore, as figure 1.1 shows, if a dollar is transferred from the rich to the poor, the loss of utility to the rich will be less than the gain in utility to the poor. The transfer of a dollar from the rich person to the poor person will therefore increase the sum of utilities of these two individuals. Where should the process of redistribution stop? When each person has the same amount of money, because this will maximize the sum of their utilities. The pie of happiness is biggest—and therefore Utilitarian Efficiency is achieved—when the pie is divided exactly equally.

Definition: Utilitarian-Efficient Policy. A policy is Utilitarian efficient if it maximizes the sum of utilities in society.

Bentham was an effective agitator for equality. At the time, admission to Cambridge and Oxford was limited to students who belonged to the Church of England. When University College London opened in 1826, it was open to all. Bentham was considered the spiritual father of University College and his embalmed body is to this day displayed as a public sculpture there. (The head is now wax because pranksters stole the real head several times.)

But Utilitarianism as a yardstick for economic efficiency did not survive the century in which it was developed. It was supplanted wholly and with complete success by another definition of efficiency, one invented by an Italian economist, Vilfredo Pareto (1848–1923). If Utilitarianism is still mentioned in economics textbooks at all, it is summarily dismissed as a historical curiosity on the way to the truth: Pareto efficiency. How and why did Pareto dismiss Utilitarianism?

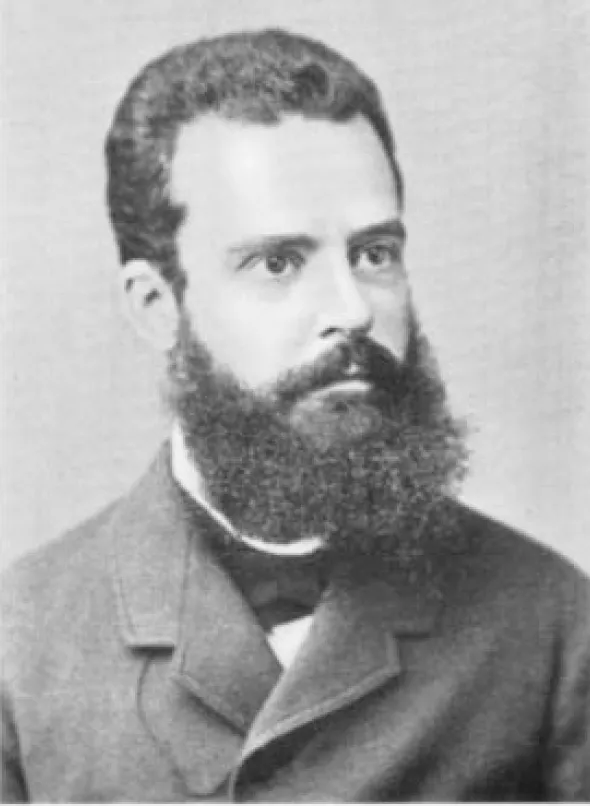

FIGURE 1.2: JEREMY BENTHAM, 1748–1832

“The more nearly the actual proportion approaches to equality, the greater will be the mass of happiness.” Credit: Michael Reeve

THE POPE AND PARETO DON’T LIKE IT

Let’s begin with the why. At the end of the nineteenth century, inequality in Europe was so extreme that a socialist revolution had become a real possibility. Pope Leo XIII was moved enough by the prevailing economic disparity that in 1891 he issued an encyclical letter, Rerum Novarum (Of New Things), which was devoted to “The Condition of the Working Classes,” and in which he wrote:

The whole process of production as well as trade in every kind of goods has been brought almost entirely under the power of a few, so that a very few rich and exceedingly rich men have laid a yoke almost of slavery on the unnumbered masses of non-owning workers.1

This would seem to lay the groundwork for a call to redistribute “the whole process of production.”In fact, though, the pope objected strongly to redistribution through the power of the state. The rich should have no legal obligation to assist the poor, the pope claimed:“These [assisting the poor] are duties not of justice, except in cases of extreme need, but of Christian charity, which obviously cannot be enforced by legal action.” In a book published in 1906, Manual of Political Economy, Pareto elaborated on why assistance to the poor cannot be legally mandated, warning against even a mild redistribution by the state because of the slippery slope:

Those who demanded equality of taxes to aid the poor did not imagine that there would be a progressive tax at the expense of the rich, and a system in which the taxes are voted by those who do not pay them, so that one sometimes hears the following reasoning shamelessly made: “Tax A falls only on wealthy persons and it will be used for expenditures which will be useful only to the less fortunate; thus it will surely be approved by the majority of voters.”2

But why was Pareto opposed to redistribution? Because according to him Bentham was not necessarily right. As figure 1.1 shows, Bentham assumed that the only difference between a rich person and poor person was in how much money they had: given the same amounts of money they would have exactly the same amounts of utility. It is this similarity between the rich and the poor that led Bentham to conclude that transferring a dollar from the rich to the poor would hurt the rich less than it would help the poor. But according to Pareto rich people and poor people may be fundamentally different. In this scenario transferring money from the rich to the poor could actually hurt the rich more than it would help the poor. He used an extreme hypothetical example to illustrate this possibility. What if the rich actually enjoy the poverty of the poor? He asked. Then reducing poverty by redistribution may hurt the rich more than it would help the poor, Pareto argued. “Assume a collectivity made up of a wolf and a sheep,” Pareto explained. “The happiness of the wolf consists in eating the sheep, that of the sheep in not being eaten. How is this collectivity to be made happy?”3

Economists do not usually cite this passage in explaining Pareto’s objection to Utilitarianism. Instead they ask what if the rich and the poor do not have the same utility function, as in figure 1.1, but instead, by chance, the rich happen to derive greater utility from a given quantity of money than the poor do. Figure 1.3 depicts this argument graphically, and it shows that a transfer of a dollar from the rich to the poor in this case may hurt the rich more than it would help the poor. Notice that just like a poor person, a rich person also derives greater utility from her first dollar than from her last one. But a rich person’s utility from her last dollar may exceed the poor person’s utility from her first dollar.

What would happen if all of a sudden the rich and the poor traded places, and the rich became poor and the poor became rich? In this case the curves in figure 1.3 would stay the same, but their labels would change: the lower curve would become the utility function of the rich and the upper curve would become the utility function of the poor. In this case, transferring money from the rich to the poor would increase the sum of utilities and redistribution would be justified.

FIGURE 1.3: UTILITY FUNCTIONS OF THE RICH AND THE POOR

Economists do not claim that the situation as it is described in figure 1.3 actually exists in reality, only that it may exist. Because utility is not measurable, this possibility simply cannot be ruled out. And if this is indeed the situation, then Bentham’s argument does not hold, and redistribution is therefore not justified. Bentham acknowledged this possibility. “Difference of character is inscrutable,” he said.4 But, he argued, a large difference in character between the rich and the poor was so unlikely that the government would make fewer mistakes if it operated under the assumption that the rich and the poor are similar, than if it operated under the assumption that they are fantastically different. The economist Abba Lerner (1903–82) noted that Bentham was just applying the first principle of statistics: when it is not known that things that appear the same are really different, the best we can do is to assume that they are the same.5 This is why we assign the probability of1/6 to each face of a die.

FIGURE 1.4: VILFREDO PARETO, 1848–1923

“Assume a collectivity made up of a wolf and a...