![]()

1

The Eastern Gate of Fort Akita

秋田城東門

The snow is falling steadily around the bleak Eastern Gate of Fort Akita, an isolated outpost of the imperial Japanese government built in 733 in Tōhoku, the extreme northern part of the main island of Honshū. The fort’s walls are made from rammed earth above a shallow foundation of undressed stone. Sandy soil, dug from a depth sufficient to guarantee that no seeds would be present, was mixed with water and carried up ladders to be applied in a series of layers that were firmly rammed down. The final stage was to give the wall a coating of plaster and add a tiled roof to weatherproof it.

The overhanging eaves of the solid wooden gate provide some shelter for the reluctant conscript guards who have been sent to this remote area, although Fort Akita is in fact quite luxurious compared to some of the smaller wooden stockades that it supports out in the forests and mountains. Inside the strong defensive walls is a complex headquarters base from where civilian officials administer these frontier territories. The sentries in the gate house keep a look out for the enemies who are usually referred to as emishi, a name that signifies a belief that they are barbarians. They are fiercely independent, and their raids on the forts unsettle the Chinese-inspired civilisation that the central government in Nara is so eager to promote and extend throughout Japan.

A constant supply of troops is needed to defend these precarious outposts, and it may be a request for more soldiers that the official in the smaller picture is writing on one of the wooden strips that were used instead of paper. The men who will be sent north in response to his request will be unwilling conscripts taken from their fields, given a modicum of training and despatched to wild and snowy Tōhoku for years at a time. There is a saying that a man conscripted for military service will be unlikely to return until his hair has grown white, and this largely infantry army are no match for the men who lurk out there in the vast snowy forests of Tōhoku. In fact the system will eventually collapse, and in the year 792 the conscription of farmers will be replaced by something else: the hiring of the highly skilled elite warriors known as samurai.

![]()

2

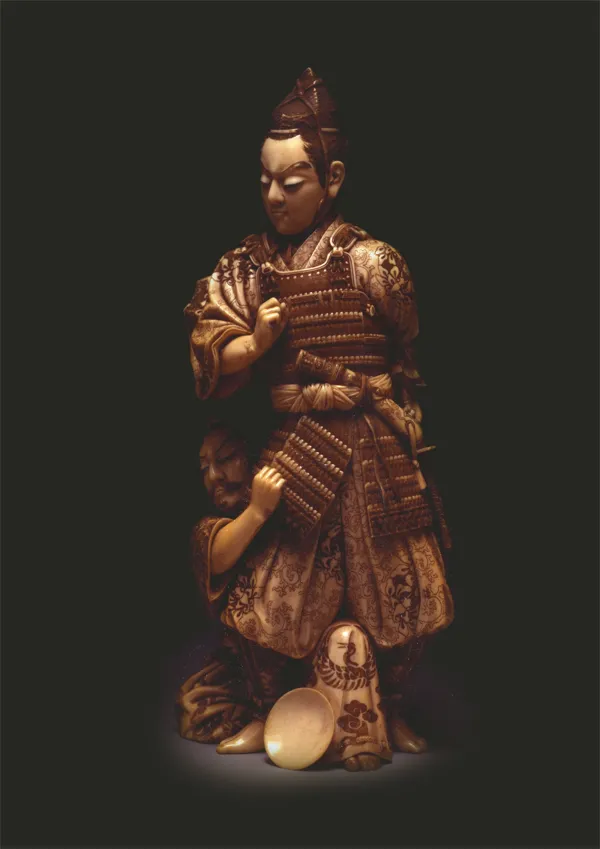

An Ivory Carving of Samurai

武士の象牙の彫刻

In this ivory carving two warriors are shown grappling with each other. They are referred to as samurai (literally ‘those who serve’) and are the followers of powerful local landowners who have been commissioned to fight the emperor’s wars in place of the hopeless conscript armies. By the end of the eighth century these trusted warrior families have grown rich in imperial service. Their samurai are highly valued fighters because they are familiar with the areas they live in and have honed their military skills over many decades. Even though the emishi problem has been curtailed there are still sporadic dangers from rebels, bandits and pirates, and southern Japan occasionally faces threats of invasion from China and Korea. There is also the need to provide a guard for the imperial capital, a duty that places the samurai at the heart of government.

At first the samurai system worked well, and when rebels arose or succession disputes happened the hired warriors were content to do their duty for the imperial court and receive their just rewards, but it was not long before some serious developments occurred. The ninth century was a time of economic decline marked by plagues and episodes of starvation, all factors that led to resentment against the central government. By the end of the century the embattled court was reluctantly forced to grant far-reaching powers to its provincial governors to levy troops and to act on their own initiatives when disorder threatened.

The first major test for the system happened in 935 with the revolt of Taira Masakado. He was the descendant of an imperial prince who had been sent to the Kantō (the area around modern Tokyo) to quell a rebellion and had been granted the surname of ‘Taira’, which may be translated as ‘the pacifier’. The Taira clan grew to be so important that a minor succession dispute within their family quickly developed into a serious armed uprising against imperial authority. At the height of his rebellion Taira Masakado even proclaimed himself as the new emperor, but an army supplied at a provincial level eventually overcame the revolt and Masakado was beheaded in 940.

Taira Masakado’s army consisted of samurai who were elite mounted horsemen supported by foot soldiers. So exclusive did warrior houses like the Taira become that anyone who presumed to wield a bow in the service of the emperor and could not demonstrate that he was of the lineage of a military house stood little chance of promotion or advancement. In 1028, for example, a certain Fujiwara Norimoto who was recognised for his martial accomplishments was sidelined for being ‘not of warrior blood’. By contrast, in 1046 Minamoto Yorinobu could reel off a pedigree that went back twenty-one generations. The social elite of the samurai class was now firmly established.

![]()

3

An ebira or Quiver

箙

Of all the weapons wielded by the first samurai none was more highly regarded than the yumi, the Japanese longbow, for which arrows were stored in an ebira (quiver) like the one shown here. It is covered in bear fur and carries a design of a dragonfly. The sharp arrow heads rested securely in the lower basket which would be tied to the samurai’s belt, and the feathered arrows, made from the straightest possible bamboo, were withdrawn by lifting them clear of the quiver and pulling them downwards. The wooden reel hanging from the quiver holds a spare bowstring coated with wax to give a hard, smooth surface.

Popular culture may laud the famous samurai sword for being the ‘soul of the samurai’, but that concept lay a few centuries into the future, and a passage in the chronicle Konjaku Monogatari provides a surprise for anyone brought up with the tradition of the sword’s priority over the bow. One night some robbers attacked a samurai called Tachibana Norimitsu. He was armed only with a sword, and ‘Norimitsu crouched down and looked around, but as he could not see any sign of a bow, but only a great glittering sword, he thought with relief, “It’s not a bow at any rate”’.

Norimitsu did in fact vanquish the robbers, but his evident relief that he was not up against anyone armed with a bow is very telling. A bow in the hands of a skilled archer, which is what all elite samurai were trained to be, gave him a considerable advantage over a swordsman who could be incapacitated before he came within striking distance. Nevertheless, the Japanese longbow had nothing like the power of the bows wielded by the mounted warriors from the steppes of Central Asia.

The maximum effective range of a Japanese arrow was unlikely to be more than about 20 metres, and the preferred distance for inflicting a wound or killing an opponent through a weak point in his armour was little more than 10 metres. A further limitation on an archer’s skills was that his human target did not usually remain static and was no doubt trying to kill the attacker at the same time. An added complication was provided by the box-like design of the yoroi style of armour, which meant that the angle of fire of a bow was considerably restricted. The mounted archer could only shoot to his left side along an arc of about 45 degrees from about ‘nine o’clock’ to ‘eleven o’clock’ relative to the forward direction of movement; the horse’s neck prevented any closer angle firing.

![]()

4

A Samurai Helmet

兜

The style of armour worn by samurai between the tenth and thirteenth centuries was known as a yoroi, and at first sight a yoroi, as exemplified by the ornate kabuto (helmet) shown here, looks like a very colourful, elaborate and even flimsy version of anything that could be called a suit of armour.

It was put together from several different sections made not from large solid plates or chain mail in the European style but from a number of small scales tied together then lacquered to weatherproof them, a type of armour common throughout much of East Asia. Rows of these scales were combined into strong yet flexible armour plates by binding them together with silk or leather cords. The resulting yoroi provided good protection for the body for an overall weight of about 30 kilograms.

The one exception to the lacquered-scale model was the helmet bowl that provided a solid protection for the head, and this modern reconstruction of a typical twelfth century helmet for a high-ranking and wealthy samurai provides an excellent illustration. Helmet bowls were made from separate iron plates fastened together with large projecting conical rivets. A peak, the mabisashi, was riveted on to the front and covered with patterned leather, while the neck was protected by a wide and heavy five-piece neck guard called a shikoro, which hung from the bowl. The red silk cords that hold the sections of the shikoro together would also be found in the body of the armour, giving it a characteristically colourful appearance. The top four plates of the shikoro were folded back at the front to form the fukigayeshi, which stopped downward sword cuts aimed at the horizontal lacing of the shikoro. Normally an eboshi (cap) was worn under the helmet as padding, but if the samurai’s hair was very long his motodori (pigtail) was allowed to pass through the tehen, the hole in the centre of the helmet’s crown where the plates met. The raised sides of the tehen can just be seen. Two lively additions to the basic helmet shown in this example are the grinning oni (devil) face on the front of the peak and the slender graceful kuwagata (ornamental ‘antlers’).

![]()

5

Picture Scroll of the Later Three Years’ War

後三年の役絵巻

It is difficult not to wince when looking at this contemporary piece of evidence showing the damage a Japanese longbow could do to a human body. The samurai victim, who is displaying immense self-control, has an arrow lodged in his cheek. While one of his comrades holds his head firmly another attempts to extract the broken shaft using a pair of iron pincers. If they are successful he will probably survive.

The samurai’s yoroi armour on the scroll is much simpler than the one exemplified earlier by the elaborate helmet, because these men are not wealthy generals but ordinary warriors. There are no golden ornaments on their armour, their feet are bare and they sport whiskers, yet all are samurai, as shown by the quivers at their sides, their iron shin guards and the heavy iron helmets.

They are combatants in the ‘Later Three Years’ War’ (Gosannen no eki), the curious name given to a fierce war fought between rival samurai clans during the eleventh century. It had its origins in the rivalry between various samurai families who had acquired governorships from the imperial court and then used their positions to enrich themselves. Much political chicanery went into having one’s deadliest enemy declared a rebel against the throne. If the ploy was successful anyone who overcame the rebel would expect a reward, and an earlier conflict known as the Former Nine Years’ War had made Minamoto Yoshiie (1041-11...