![]()

Chapter 1

SELBY’S TRADE ON THE YORKSHIRE OUSE

‘Selby is situated on the west bank of the Ouse which glides by in a deep, broad and majestic stream.’

(S.R. Clark’s Gazetteer, 1828)

The River Ouse does indeed glide through Selby in a quiet yet stately way, but its passage is now almost completely ignored by those who live in town and style themselves Selebians. There are periodic concerns about flooding and the occasional inconvenience on the rare occasions that the road or rail bridges have to swing open to allow a pleasure boat to pass, but for long periods of time, the river has become an irrelevance.

This worthlessness is a very recent development. From Viking ships coming upriver for the battles of Fulford and Stamford Bridge in 1066 and Abbot Benedict’s vision of three swans that led to the foundation of Selby Abbey in 1069, until the final decade of the twentieth century, trade and employment in Selby were centred on the riverside. This chapter describes the history and development of commerce on the river, problems that are encountered in its navigation, and first-hand accounts of those who depended on it for their livelihood.

The Ouse at Selby is no ordinary river. Such is the vastness of the Humber’s estuary that the Ouse, one of its two tributaries, experiences tides at Selby, despite being more than sixty miles from the sea. In fact, Selby was not the furthest extent of the tide. Trinity House, the authority on all matters maritime, explained in 1698

‘Popleton ffery wch is about 4 miles above ye Citty of York (and) we could not reach yt except upon extraordinary Tides.’

Poppleton is around eighty miles by river from the North Sea. It was only with the construction of Naburn Lock in 1757 that the effects of the tidal flow to York and further up the river were restricted. To gain a full understanding of Selby’s river, one needs to begin with a consideration of her tides, meanders and mood swings. A tidal river has many more intriguing properties than one which merely flows in a constant direction at a steady pace. A tide is a mighty pulse of water caused by the gravitational effects of the Sun and Moon. This pulsation of water that brings high tide to the north-east coast of the UK is generated in the Atlantic. A mass of water travels around the northern coast of Scotland and down the eastern one of England, before meeting a similar pulse which has moved up the English Channel. This conflict produces the tidal surge seen as the flood tide that produces a flow that makes it seem that the river is moving uphill.

The actual time of high water on the north-east coast changes the further south one travels. If high water at Aberdeen is at midnight, high water at Whitby is around three in the morning and at Spurn Head 4am. This tide then sweeps into the Humber estuary and high water at Hull will be at around five, at Trent Falls, the confluence of the Ouse and Trent, at 5.30 and at Selby at a little after seven. Poppleton would have been reached around 10am. These periodic changes have a serious effect on river navigation, in three ways, and sailors would have to be aware of the effects of each of them: the length of time the tides ‘run’; the change in depth of the river; and the velocity of the current.

This tide does not run for an equal amount of time on all parts of the river. In general, the nearer to the coast, the longer the flood tide holds sway. Because there are two tides every 24½ hours, at the coast, each flood tide runs for just over 6 hours. At Hull the incoming tide runs for about 5½ hours, but at Selby, for only 2½. Like high water, low water occurs at different times on the river. Since the flood tide lasts a shorter time the further you are from the sea, then the duration of the ebb, when water is flowing back towards the sea, must increase to keep the tidal cycle of a high tide every 12¼ hours. So, if the flood at Selby lasts for 2½ hours, after a very short period of slack water the gentler ebb must begin, lasting about 10 hours.

As the tide comes in, water is pushed up the river, so increasing the river’s depth. The difference in height between when the river is at its lowest and that when all the flood tide has passed is the river’s ‘range’. This range depends on the effect of the Moon’s gravity on the Earth. Tides are highest at new or full moon, and gradually fall, then rise, in the fortnight between them. In its extreme at Selby the range is 15ft (4.7m). If you are mooring your boat on the river, you need to know how much rope to allow for the tide!

The velocity at which water travels upstream depends on the depth of the channel it meets. As the river becomes shallower, the velocity of the flow increases. On the Ouse at Selby, the flood tide runs at speeds up to 8 knots, which is much faster than most river craft can travel under their own power. The power of the current is not to be treated lightly. The Gentleman’s Magazine of August 1811 reports that:

‘John Bateman of Selby, master of the brig William, was proceeding up the Humber when she was driven by the strength of tide upon Whitton Sand [bank]. The rapidity of the current … forced her broadside [lying across the current] and the captain’s wife, two of his children and a female passenger, were drowned as the water rushed into the cabin with overwhelming fury.’

Twice every day, mariners on the Ouse had to get used to these variations in the direction, depth and speed of flow of the river.

A further effect of the tidal flow is a river wave. Under certain conditions, normally around full or new moon, and around the equinoxes in September and March, the incoming rush meets the natural downward flow of the river with such a force that a wave is produced. This effect has long been experienced, and names for it around Yorkshire reflect the language of the Viking invaders of a millennium ago with Norse-based names such as eagre, aegre or aegir.

The wave is more commonly known as a river bore, which is also derived from an Old Norse word, bara, meaning a wave. Whilst the Rivers Severn and Trent are famous for their inland waves, that on the Ouse can be equally spectacular. The bore marks the leading edge of the tide, and once passed, the pulse of water surges upriver at high speed, carrying all manner of flotsam, making an impressive sight for onlookers, and one has to be wary of if it on the river.

The phenomenon moved Elizabethan poet Michael Drayton to write:

‘When flood comes to the deep,

The Humber is heard most horribly to roar,

When my aegir comes I make either shore,

Tremble with the sound that I afar do send.’

Francis Drake, historian of York, described the bore in 1736 as ‘a strange, back current of water … [it] makes a mighty noise at its approach’. More than a century later, Bulmer’s Gazetteer of the Rivers of the East Riding in 1892 provides more detail:

‘When the tide begins to flow in the [Humber] estuary the waters of the Ouse rise with startling suddenness, and occasionally with considerable violence. This peculiar rising or water-rush is locally known as the “Ager”, a name of doubtful origin, but supposed by many writers to have been derived from Oegir, the terrible water-god of our Teutonic ancestors.’

This wave can dislodge vessels at their moorings. A sudden snapping and loosing of the craft into the river results if the bore and its flood tide are not heeded. River workers were aware of its threat and working keel men in Selby would cry ‘Wild [or “wor”] aegir’ on sighting the crest of the wave.

Construction of river walls at the confluence of Trent and Ouse around 1930 to increase the navigable depth of the river to Goole has reduced the bore’s force, but it is still worth looking out for.

Since this flood tide is so powerful, it might be thought that navigation up river would be simple – wait at Hull or Goole until the tide is due, and just surf up on the inrushing ‘first of the flood’. Sadly, life isn’t that easy. It is certainly the case that ships try to leave their moorings to catch the flood, but the tidal flow actually outruns anything carried on it.

When craft were powered by the wind, the best that could be done was to go with the flood until slack water arrived. Judicious use of sails and tacking across the river could carry a ship a little further upstream, but eventually it would be necessary to drop anchor. Out would come the pack of cards whilst the mariners waited for the tide to turn. Many tides could be needed to bring a sailing ship up from Hull to Selby or York. Instead of lying becalmed, it was possible to tow ships along socalled haling or towing paths. However, like the roads, they could often be so poorly made that they were impossible for horses to use.

The advent of motorised craft in the early part of the nineteenth century overcame these problems to an extent. It was now more possible to keep up with the flow, and a good trip from Hull to Selby could be achieved in six hours.

Working with the tides is not the only problem. The navigable channel of the river constantly varies. Since this channel in the Ouse depends on how the flow of water scours it out, the correct course to follow depends on the time of year and the state of tide. Firstly, particles of mud caught up in the current are responsible for changes in the depth of the navigation channel. The major source of this silt in the river bed derives from the flood tide’s work of carrying up mud from the soft cliffs of Holderness. During summer and autumn, the fast-moving flood tide carries material for a considerable distance up-river, but the ebb lacks the power under normal conditions to remove it. On each tide, the bed of the river therefore rises a little. It is only with the torrents of fresh water caused by winter rain and melting snow that the deposits are washed back out to sea.

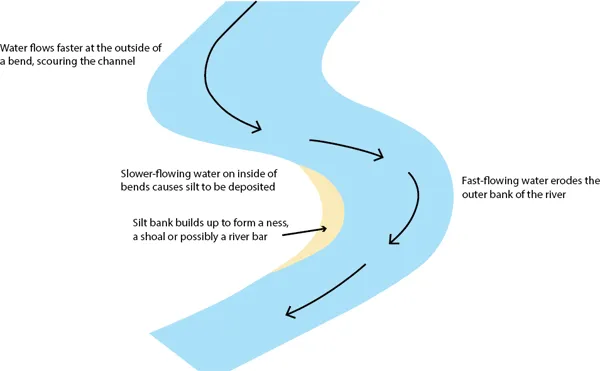

The shifting river channel at a meander

A diagram showing how the movement of the river current in a meander affects the navigation channel. (Author)

A second point to consider is the twistiness of the Ouse’s course. Its many hoops and bights, bends and meanders, require careful piloting to keep to the navigable channel, since the depth of water varies across the width of a river bend. Currents in a river tend to flow towards the outside of a bend. Without vigilant steering, craft would go with the flow, giving rise to some problems.

A combination of flow patterns and bends leads to potential problems with grounding. The silt tends to build up in the slacker sections of the river, such as the insides of bends, where nesses form. If your boat was caught on a ness, at the very best, there was a wait of twelve hours for the next high tide. If particularly unfortunate and the level of the tides was dropping from day to day, you might have to wait for a fortnight until the gravity of the moon was at its maximum effect, and the tides were sufficiently high to refloat the vessel. In the meantime, the possibility of the vessel breaking its back by being only partially supported by water was an ever-present problem.

In the slacker water of summer, nesses extend further and further into the river course, leading to shoals of shallow water. If such a shoal develops, in extreme cases river islands can be created, with ebb and flood tides running in different channels around this temporary feature. In the quieter conditions of summer, shoals can stretch across the entire width of the river, creating a bar. These features tend to be washed away when winter rains increase a river’s natural flow. Laurie’s tales describe how a mariner had to face and surmount these challenges raised by Mother Nature.

A river pilot was skilled indeed to be able to understand and counter all these natural nuances and any craft hoping to voyage successfully to and from Selby and the coast would need to be crewed by seamen astute and experienced enough to deal with such problems. At the very least, boats carried long poles to push the boat away from any shallows and doughty ropes that could be attached to riverside trees to allow muscle power to shift the boat if grounded.

An example of these navigation problems is acutely described by well-known nineteenth century traveller, George Head. He describes the pitfalls involved during his voyage from Selby to Hull that began after breakfast one morning:

‘The navigation of the Ouse and Humber, owing to shoals and shifting sands, is as bad as can be, at all times. This morning the tide was fast ebbing, and though starting one minute sooner might possibly have operated in our favour, in point of fact, the chances were about ten to one that we would be stuck in the mud.

‘Doubts were soon expressed by those partially acquainted with the river as to whether the ebb was not too far advanced. Before we had been a couple of hours on the way, indications appeared sufficient to set speculation at rest, for the water became as thick as a puddle, so that it actually retarded the rate of the steamer; and two men, one on each side, each with a checkered pole in his hands, continually announced the soundings.

‘We were tantalized for some time by hearing “six foot, five foot, five and a half foot, five foot” and so on, till at last came “four and a half foot” and then she stuck.

‘As it turned out, this not happening to be the spot whereon the captain had made up his mind to repose, he was active and anxious to get the vessel afloat, and in this object received able support from all his passengers, who, about forty in number, condescendingly acted in concert under his directions, and shuffled across from one side to another so as to keep her going, and prevent her from lying quietly down on the mud.

‘Whenever, in a coarse gruff voice, he gave the emphatic word of command “Rowl her,” the crowd, like sheep at the bark of a dog, trotted across the deck, treading on one another’s heels, and suffering much personal inconvenience. At the same time they hauled upon a rope, previously sent on shore, and made fast to a purchase, till the vessel was disengaged from her soft bed, and again afloat in a channel nearer the shore.

‘We proceeded now about two miles farther, when the men with the checkered sounding poles were at work again for a few minutes, and then came an end of all uncertainty, for we touched the ground again, and in a few seconds were laid up in right earnest.

‘The captain now was ...