![]()

1

SYMMETRY

Why your left is like your right (and why it’s different)

What is a pattern, anyway? We usually think of it as something that repeats again and again. The math of symmetry can describe what this repetition may look like, as well as why some shapes seem more orderly and organized than others. That’s why symmetry is the fundamental scientific “language” of pattern and form. Symmetry describes how things may look unchanged when they are reflected in a mirror, or rotated, or moved. But our intuitions about symmetry can be deceptive. In general, shape and form in nature arise not from the “building up” of symmetry, but from the breaking of perfect symmetry—that is, from the disintegration of complete, boring uniformity, where everything looks the same, everywhere. The key question is therefore: why isn’t everything uniform? How and why does symmetry break?

People dreamed of an ordered universe even in ancient times—perhaps especially then, when they were more vulnerable to the random whims of nature. “God, wishing that all things should be good, and so far as possible nothing be imperfect,” wrote the Greek philosopher Plato in the fourth century BCE, “reduced the visible universe from disorder to order, as he judged that order was in every way better.” Plato imagined a universe created using geometric principles, based on ideas about harmony, proportion, and symmetry. It is a vision that has resonated strongly ever since. Symmetry is one of the key concepts that modern physicists use to understand the world, and they believe its deepest laws will show this feature.

What exactly are these properties of symmetry and pattern that we find in nature, and where do they come from? The best way to understand symmetry is as a property of an object or structure that allows us to change it in some way while leaving it looking just the same as it was before. Think of a sphere: you can rotate it any way you like, and you’d never know: it appears unchanged. Or think of the grid of lines on a piece of graph paper. If you move the paper exactly one grid square’s width in a direction parallel to the lines, the grid is superimposed on how it looked at the outset.

These are both symmetries, but of different kinds. The sphere has so-called rotational symmetry, meaning that its appearance is unchanged by rotation. The graph paper has (ignoring the edges) translational symmetry: a “translation” here means a movement in a particular direction. The sphere in fact has perfect rotational symmetry, meaning that it is symmetrical for any angle of rotation. Imagine instead a soccer ball made from hexagonal and pentagonal patches sewn together: only certain rotation angles will superimpose the hexagons and pentagons exactly on their initial positions.

1 SUBTLE SYMMETRY

The sand dollar, a kind of sea urchin, seems to pretend that it has fivefold symmetry, like a pentagon—but the oval slots undermine it.

2 ARE ALL PEBBLES ALIKE?

Even pebbles have, on average, a characteristic shape that can be written in mathematical terms, which describes the range of different amounts of curvature they have over their surfaces.

Another kind of symmetry is reflection, which is really just what it sounds like. If you put a mirror upright on the graph paper, the reflection in the mirror looks just like the piece of the sheet that lies behind it. This is exactly true only if the plane of the mirror is placed in just the right position: it has to run either along one of the grid lines or exactly at the halfway point of a square, so that the half-squares you can see and the other halves in the mirror reflection look like a full square. There’s another place you can put the mirror, too: exactly along the diagonals of the squares, at an angle of 45° to the grid lines. So this is another of the pattern’s “planes of symmetry.” If the angle is any different from 45°, the reflection doesn’t superimpose exactly on the original grid that it hides: that isn’t a true plane of symmetry.

“Symmetry is one of the main concepts that modern physicists use to understand the world.”

Mathematicians call these rotations, reflections, and translations “symmetry operations”—movements that don’t alter the appearance of the object. A plus sign and a square have the same symmetry: they have an identical set of operations that leaves them looking unchanged. A square grid, meanwhile, has a different set of operations from a hexagonal grid such as a bee’s honeycomb or chicken wire.

Bodies

One of the most common kinds of symmetry that we see in the natural world is called bilateral symmetry. An object with this symmetry looks unchanged if a mirror passes cleanly through its middle. To put it another way, the object has a left side and a right side that are mirror images of each other. This, of course, is a characteristic of the human body, although little random quirks and accidents of our life history make the symmetry imperfect. There’s some evidence that people whose faces are more symmetrical are deemed more attractive on average, and it has also been claimed that other animals with bilaterally symmetrical bodies have more mates the more symmetrical they are.

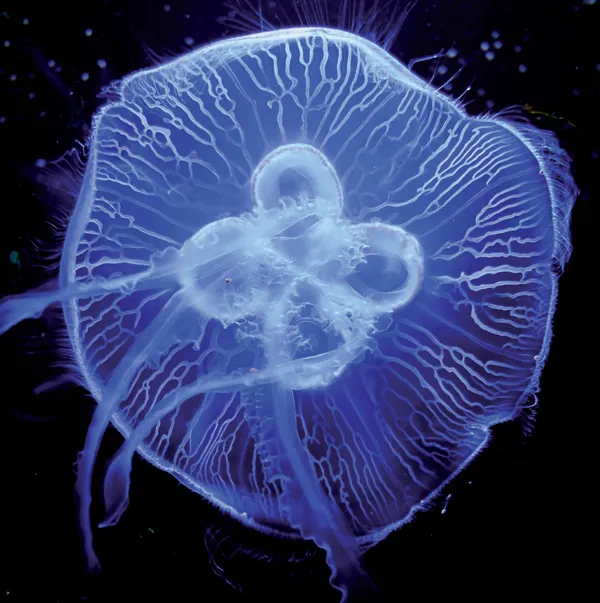

1 JELLYFISH

“Endless forms most beautiful”: this is how Charles Darwin described the shapes made by evolution.

2 LOW TIDE

Patterns in sand appear spontaneously, engraved by nature’s forces.

3 BILATERALISM

A tale of ...