![]()

IT is a commonplace that before the Romans conquered Britain, its inhabitants had reached a high level of achievement in decorative art, and that one result of the conquest was the destruction of this art and the imposition of an inartistic though materially comfortable culture. With this view I do not propose to quarrel; but in certain ways I think it may with advantage be qualified. My present concern is with one such qualification.

In the general decay of Celtic art which is supposed to have followed upon the Roman conquest, one exception stands out conspicuous. I do not refer to the objects produced by the Castor and other local potteries of Roman Britain. They include pretty and ingenious things, but it would be pedantic to call them works of art. I refer to the well-known series of brooches to which attention has been repeatedly called in this place and elsewhere. First and foremost there is what so great a virtuoso as Sir Arthur Evans has called the most fantastically beautiful creation that has come down to us from antiquity1—the gilt brooch found in the guard-room at Great Chesters. The Aesica Brooch, as it is generally called, is not an isolated thing. It is, as it were, surrounded by a cloud of witnesses to the artistic competence of the people who produced it. At the moment I need only remind you of two classes of brooch, the so-called trumpet- or harp-brooches, and the S-shaped or dragonesque. The strange beauty which inspired a German archaeologist, when he found a perfectly ordinary specimen of British trumpet-brooch, to call it a product of Africa,2 has never, I think, failed to impress any one who has studied these objects.

Of all these brooches, none, so far as we know, was made before the Roman conquest of Britain. That is universally admitted. But, it is said, they were made in the least Romanized parts of the country, the north, the west, and even in unconquered Caledonia, to which Sir Arthur Evans ascribes the Aesica Brooch. It is implied that they are the lineal successors of the pre-Roman Celtic art of Britain, enjoying a last afterglow in the regions as yet unpenetrated by Roman influence.

This is another of the things which require, not so much to be contradicted, as to be qualified. The Celtic affinities of this art seem to me to have been emphasized at the expense of its Roman affinities, which arc in fact, I contend, no less real.

To begin with the Aesica Brooch (pl. XI). Sir Arthur Evans has called attention to the fact that its ornament is like the ornament on objects found in Scotland, and is derived from the northern British style of pre-Roman art as we see it at Stanwick. But it does not seem to have been pointed out that the brooch itself, apart from its ornament, has nothing British about it whatever. Sir Arthur did certainly, in the original paper on this brooch to which I and every other student of the subject must constantly turn with fresh gratitude and admiration, bring it into relation with the brooch worn by a lady on a Roman tombstone at Mainz. But when he wrote, hardly any brooches closely resembling the Aesica Brooch in shape were known. We now possess quite a large number of them, and, as will be shown below, their distribution does not suggest that the Aesica Brooch was a product of Caledonian art.

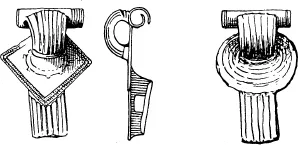

Fig. 1. Thistle-brooches. (1/2)

The Aesica Brooch, as Sir Arthur showed, is derived from the type which German antiquaries call the thistle-brooch (fig. 1). With its humped and reeded bow, its reeded tail like that of a bird, and the disc lying flat on the base of the tail and serving to anchor the foot of the bow to the body of the brooch, this is a remarkably individual and recognizable form; and its dating and distribution are now well established, though the evidence on which the dating is based has mostly come to hand since Sir Arthur’s paper was written. It is very common at Roman sites of the early and middle first century in north-western Europe. At Mont Beuvray it appears with a pre-Roman date; but its associations in the Rhineland are not pre-Roman but definitely Roman, and belong to the first half of the first century. In this country it is rare; but when it does occur it is always at places which felt the influence of the Roman invasion at a very early date. Thus we find it at Canterbury, at Lincoln, at Richborough, at South Ferriby, a site remarkable for its large collection of early objects, at Hod Hill, and even in the native village at Cold Kitchen Hill, where a very curious selection of early Roman things has been found. I need not attempt a complete list, but I think it is beyond doubt that wherever we find thistle-brooches in Britain they represent an intrusion of Continental influence in the first years of the Roman occupation. Not a single example has been found which seems to have been in this country before the Romans came, and not a single example which seems to have been in use as late as the Flavian period.

The thistle-brooch, then, is a type which belongs not to Britain but to the Continent, and had already passed almost out of use by the time of the Roman conquest. From this type the Aesica Brooch is patently derived. When and where did this derivation take place ?

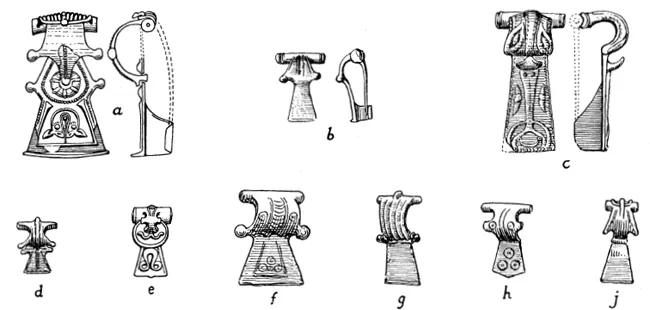

To begin with the when. The Aesica Brooch is not a thistle-brooch, but a fan-tailed type differing from it, though in close relation to it (fig. 2). This fan-tailed type recurs at Hook Norton (P. S. A. xxiii, 407), at Wylye Camp and at Winterbourne Basset (W. A. M. xxxv, 404), at Wroxeter (Wr. 1912, no. 3), at Woodeaton (J. R. S. vii, p. 114, no. 61), at Canterbury (Ant. Journ, iv, 153), at Camerton (V. C. H. Som. i, 293), at Lydney (Bledisloe collection), at Camelon in Scotland (P. S. A. Scot. xxxv, 403), at South Cerney and Grantchester (Evans Collection, Oxford), and at Santon Downham (Camb. Arch. Soc. xiii, 159). Of these examples, only one was found in a deposit of such a kind as to fix the date at which it was in use: namely the Wroxeter example, which dates probably from the early second century. The Canterbury example ought perhaps to be regarded as intermediate between this class and that to which the famous Birdlip brooch belongs.

Fig. 2. Bow and fan-tail brooches (1...