Base of the Pyramid Markets in Affluent Countries

Innovation and challenges to sustainability

Stefan Gold, Marlen Gabriele Arnold, Judy N. Muthuri, Ximena Rueda, Stefan Gold, Marlen Gabriele Arnold, Judy N. Muthuri, Ximena Rueda

- 152 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

Base of the Pyramid Markets in Affluent Countries

Innovation and challenges to sustainability

Stefan Gold, Marlen Gabriele Arnold, Judy N. Muthuri, Ximena Rueda, Stefan Gold, Marlen Gabriele Arnold, Judy N. Muthuri, Ximena Rueda

Über dieses Buch

The Frugal Innovation and Bottom of the Pyramid Markets series comprises four volumes, covering theoretical perspectives, themes and various aspects of interest across four key geographical regions where BOP markets are located - South America, Asia, Africa and more engineered countries. BOP always addresses the poorest people or socioeconomic order or groups within a country, society, region or continent, t hus, this series contributes a profound understanding of BOP markets across the most important geographical areas around the world and presents valuable insights on how the private sector can work together with other stakeholders to develop and operationalize economically viable business models in BOP markets, all the while contributing to sustainable development. Private actors such as multinationals, SMEs and entrepreneurs have a critical role to play in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals agenda as laid down by United Nations in September 2015. Yet, BOP markets face unique challenges and the private sector alone cannot orchestrate sustainable value creation activities.

Each volume presents several theoretical strands that highlight the diverse approaches and solutions to developing BOP markets further. Frugal, reverse and inclusive innovations can foster (sustainable) development and provide new business models and value streams that other countries can also benefit from. A variety of stylistic elements, such as research work, interviews and roundtable discussions, offer a wide and vivid impression of ongoing challenges and fruitful solutions.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Information

Part I

1 The Base of the Pyramid markets in affluent countries

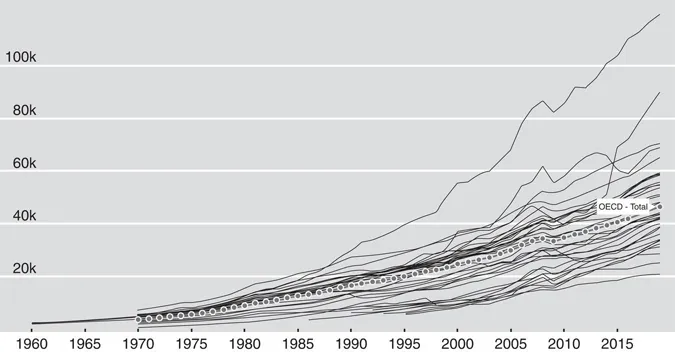

Introduction: Economic development in affluent countries and BOP

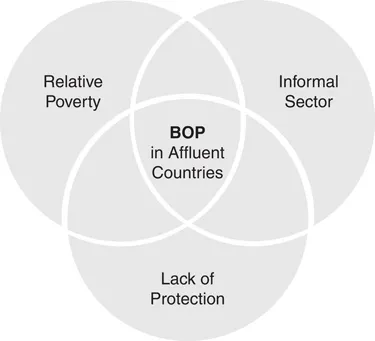

BOP markets (BOPMs)

| BOPM principle | Definition (London, 2008) | Developing countries | Affluent countries | Example affluent countries: The Big Issue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

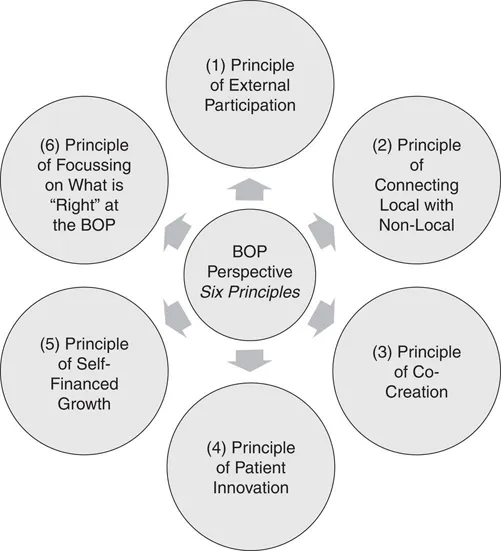

External Participation | ‘Requires the entry of an exogenous, or external, venture or entrepreneur into the informal economy’ | multinational corporations, domestic firms, NGOs, non-native individuals, … | Mostly NGOs and ecclesiastical organisations as well as former BOP-firms | The Big Issue Foundation cooperates with homeless people, allowing them to sell their paper for a profit |

Connecting Local with Non-Local | ‘Either bringing non-locally produced products to BOP markets [BOP as consumer], or by taking BOP-produced goods or services to non-local markets [BOP as producer]’ | BOP as consumer: providing goods and services not currently offered in local markets; BOP as producer: taking locally produced goods and selling them in other (e.g. affluent country); marketsCombination: take a locally produced good and sell this product to BOP markets in other (non-local) regions or countries | Local problem (e.g. supermarkets buying more food than they can sell resulting in food waste) connected to non-local problem (e.g. low retirement funds of elderly people resulting in hunger) trying to solve both | Unemployed people reliant on welfare or NGOs (i.e. non-local problem) combined with ‘The Big Issue was launched in 1991 […] in response to the growing number of rough sleepers in the streets of London’ (i.e. local problem) to solve issues of homelessness and creating (social) jobs |

Co-Creation | ‘Allows these ventures to combine knowledge developed at the top of the pyramid with the wisdom and expertise found at the bottom’ | Rather than relying on imported solutions from the developed world, the business model of the BOP venture and any associated technological solution is co-created among a diversity of partners, with local ownership and involvement | Not an application of pre-existing business solutions, but a collaboration top-down and bottom-up | Originally: People can buy Big Issue from their own money and re-sell it, making a profit. Nowadays: Additional, educational programmes (if wished for), trying to balance selling of magazines and providing income opportunity (bottom-up creation) with personal development through training (top-down) |

Patient Innovation | ‘Firms attempting to enter these markets must develop new problem-solving approaches, rely on different evaluation metrics, and find a structure that provides some level of isolation from the influence of existing organisational routines[, which takes time]’ | Patient Innovation: Innovation just as important as in mainstream business research, but due to lower funds more patiently. No real try-and-error possible. Patient Capital: investments start small and are then potentially scalable | BOP individuals facing handicaps (e.g. illiteracy, addictions, etc.) are reliant on knowledgeable organisations further developing individual capabilities towards a suitable(!) ideal | The Big Issue Foundation reinvests funds into workshops for their sales personnel tackling (1) personal sale goals, (2) financial handlings, (3) housing, (4) obtaining ID, (5) health and well-being, (6) addiction treatment, (7) employment, (8) education, (9) personal aspirations -> innovation through education |

Self-Financed Growth | ‘Competitive advantage and the associated long term sustainability of the venture will most likely emerge from establishing a set of mutually beneficial partnerships with local organisations and entrepreneurs currently operating at the BOP’ | Meeting the needs of the poor creates competitive advantage, that does not raise the overall playing field within the sector. Maximising the benefit of the poor = competitive advantage, that allows for slow, but self-financed growth | Organisations aiming to support BOP individuals grow through increased capabilities of its members and resulting profit; only exceptions are donations from outside that are reinvested into the cause | The Big Issue itself grows through increased sales of BOP individuals, which is achieved through learning processes and teachings (self induced growth). The Big Issue Foundation is open for external donations and reinvests its income into educational programmes for its employees, not market share growth |

Focussing on What Is ‘Right’ at the BOP | ‘This means that the BOP venture, be it a for-profit business or a non-profit initiative, ought to focus on leveraging what is “right” in BOP markets’ | The BOP perspective enhances what already exists and builds from the bottom-up. This distinguishes it from poverty alleviation approaches emphasising the development of an enabling environment. These latter efforts are more policy oriented and stres... |