eBook - ePub

A Concise History of Mining

Cedric.E. Gregory

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 216 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

A Concise History of Mining

Cedric.E. Gregory

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

A history of mining. This revised edition in a way describes the history of civilization and the early development of nations. Where minerals and mining existed, they provided ingredients for weapons, wealth and world power. The text should be useful in today's period of developing countries.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist A Concise History of Mining als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu A Concise History of Mining von Cedric.E. Gregory im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Technology & Engineering & Civil Engineering. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Part I

The Eight Ages of Man

Archaeological anthropology is the science of the evolutionary development of mankind. The first evidences of human existence have been found in recent years by the celebrated archaeologist, the late Dr. Louis B. Leakey, and his wife and son, in east Africa. Nevertheless, the earlier discoveries in Africa were made by Dr. R.A. Dart, Professor of Anatomy in the University of the Witwatersrand.

The fossil remains of man are evident only in the bony structures because the softer parts soon become decomposed and disintegrate. The gradual development of man is therefore more closely followed by studies of the artefacts associated with his manner of living. These artefacts include tools, weapons, implements, utensils and ornaments made from various materials throughout the evolutionary period of mankind. The age of the artefacts fashioned and used by primitive man can now be more precisely determined by the radiocarbon dating process.

It has become convenient to designate various periods of man’s evolutionary development as the Ages of Man, as represented by his use of various minerals and metals. These include the Stone Age, the Copper Age, the Bronze Age, the Iron Age and so on (see Table 1).

Part I covers these developments in a general way. More detailed aspects of improvements in mineral technology over the centuries are covered in Part II.

Table 1. The Eight Ages of Man.

400,000 BC | Palaeolithic (Old Stone) Age begins (using eoliths until about 40,000 BC when first reports of actual mining were noted). |

10,000 BC | Neolithic (New Stone) Age begins. |

8000 BC | Copper Age begins. |

3500 BC | Bronze Age begins. |

1400 BC | Iron Age begins. |

AD 1600 | Coal Age begins. |

AD 1850 | Petroleum Age begins. |

AD 1950 | Uranium Age begins. |

Note. The above dates are, of course, rough approximations, especially in a geographic sense.

1

Palaeolithic (Old Stone) Age (from c. 400,000 BC)

The early ape-like creatures believed to be the ancestors of true man have been found mainly in Africa, dating back more than three or four million years. They are now known as Zinjanthropus, the forebears of the Australopithecus race. Successive waves of these primitive races existed in the interglacial periods between various ice ages. These were the forerunners of modern man. They were flesh-eaters (carnivores) and therefore they depended upon wild animals for their food and, in later periods, for their clothing. They were essentially nomads, moving from place to place seeking fresh supplies of game for their existence. But they had one special need: a source of good material for fashioning weapons and hunting tools. Those who lived in western Europe were fortunate, because they found excellent deposits of flintstones occurring in layered strata in formations of limestone and chalk throughout France, Belgium, Germany and England. In this region, Palaeolithic (Old Stone) Age man displayed high levels of achievement in developing stone artefacts.

Flint is one of the many members of the silica family. Nearly all are exceedingly hard and durable, but flintstones possess a special quality in that they break into sharp-edged conchoidal flakes when subjected to pressure. These shell-like flakes can be readily adapted to form cutters, scrapers, arrow-heads, hammers and axes. Another rock, obsidian, also exhibits conchoidal fracture, but it is found only in areas of volcanic activity. In other areas, outside western Europe, these Old Stone Age people had to use other rocks, such as granite, diorite, andesite and quartzite, if flint was unavailable. Although these rocks were hard, they did not exhibit conchoidal fracture and were therefore more difficult to fashion and less reliable in use.

During one of the interglacial stages (about four million years ago), there developed a new race of hominids from the earlier genus called Australopiithecines. This has been designated as the genus Homo, with a larger brain capacity. This genus was categorised by a new species as Homo habilis and later (about 1.9 million years ago) as Homo erectus, because they walked on their hind legs. These were rough small-brained types who had discovered that sharp-edged stones were more useful in tearing apart animal flesh than were their hands and teeth. Later, Homo neanderthalensis appeared. This species produced very crude hand axes from flints. They later learned that freshly excavated flints were easier to work than the tough-skinned nodules found among the stream gravels. This is where actual mining for flints first began in earnest (see National Geographic, February 1997). These people lived in caves and wore warm clothing as the climate grew more severe. They further developed the use of stone implements as their lifestyle improved. Their life range was generally agreed to cover 50,000 years, from 80,000 to 30,000 years ago, but a recent article (see National Geographic, January 1996) accords them a life span of 200,000 years, extending the inception of this race back to 230,000 years ago.

One of the earliest clues we have to the mining activities of the ancients is associated with their funerary habits. Primitive man believed in immortality. It was understood that blood was the essence of life, and to restore life after death it was necessary to provide adequate replacement of the bodily blood lost in death. This need was provided by the custom of burying the body in a mass of red ochre powder and with lumps of red stones scattered around the grave.

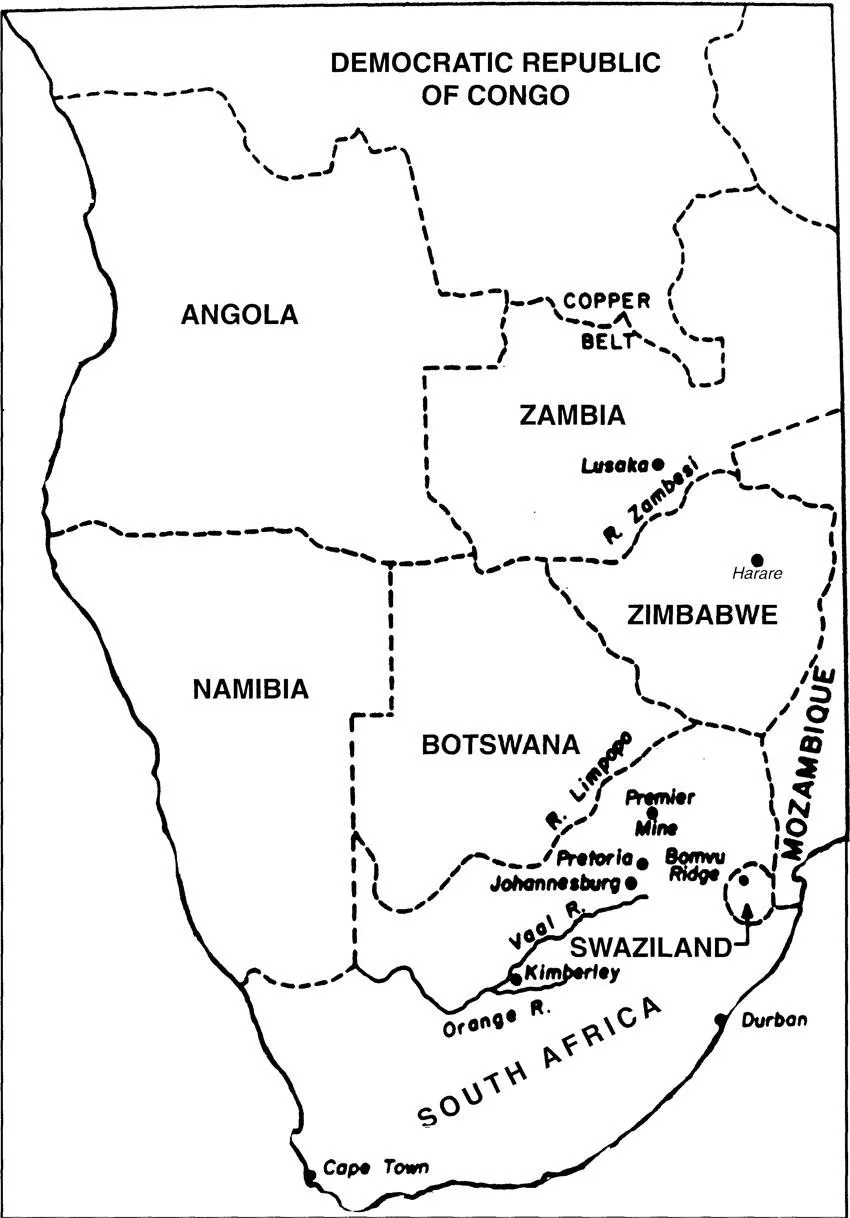

Red ochre is an oxide of iron called “haematite” by the Greeks, a word meaning bloodstone. Haematite was therefore mined in substantial quantities for these funerary and other purposes. When surface deposits had become exhausted, this powdery ore was mined underground, as in Bomvu Ridge in Swaziland (see Figure 1). Bomvu Ridge is therefore the oldest known mine in the world. In 1957–58, the Swaziland Iron Ore Development Company was formed to explore this same deposit. Some 48 million tons of massive haematite ore, averaging 60% iron, were developed. This mine was placed in production in August 1964, some 40,000 years later. It is not clear from present evidence as to the earliest time of original mining activity. Although flintstones had been used many millennia earlier, it can be supposed that these were mainly by selection of stones (eoliths) lying on the surface or in the beds of streams. We do know, however, that in late Acheulian times the practice had developed of excavating flint from beds of limestone exposed in the banks of rivers or in hilly country. This may be assumed to be the earliest form of simple mining activity, about 40,000 years ago. Nevertheless, the mining of ochreous haematitic iron ore at Bomvu Ridge is believed also to have begun up to 40,000 years ago.

Some time after the last Ice Age, about 35,000 years ago, the Cro-Magnons spread westward into Europe, perhaps from Asia, to seek better hunting grounds. These “true men”, Homo sapiens, gradually absorbed or replaced the Neanderthals and flourished in an environment of excellent flint deposits, with an abundance of caves and good hunting potential. They were an advanced race of people. One of their more useful developments was in flintstone technology: they found that stones of flint produced much better and more uniform flakes or shells when pressure was applied than when struck. This was a significant advantage in that very thin sharp flint blades could thereby be produced for tipping spears, darts, javelins and fish hooks. Flint then became a luxury and represented the acme of mineral possession for thousands of years. Later on, these people developed fine tools and needles for stitching garments and for fishing. These were made from the bones of animals. The Cro-Magnons were a talented race; they developed some beautifully decorated art forms on bone and ivory sculptures with ochres and pigments.

The Old Stone Age came to a close about 10,000 BC, after covering nearly half a million years of man’s early existence. During this time range, early man had invented most of the fundamental stone tools that were to serve his descendants for many thousands of years to come. Men of the Old Stone Age had been the first to find and use the earth’s primary mineral resources. At the close of the Palaeolithic era, Cro-Magnon man was being assimilated by newer races invading western Europe from the Baltic region, from the eastern Mediterranean, and also from North Africa.

2

Neolithic (New Stone) Age (from c. 10,000 BC)

The Neolithic Stone Age was also called the Age of Civilisation, because this is when the earliest signs of organised society appeared, with several revolutionary changes in early man’s lifestyle. Among the new arts developed were the polishing of stone tools, the making of pottery, the domestication of wild animals, and the use of seeds and plants leading to the cultivation of land and the growing of crops for food. The nomadic way of life was thenceforth abandoned. A more settled existence brought about the establishment of villages with a consequent increase in the population, which incidentally increased the demand for stone tools.

Flint had become an important and valuable resource. Those tribes possessing good workable deposits of flint experienced an industrial boom. Certain localities became famous for the quality of flint mined and implements produced. In England, Belgium, France and Sweden, shafts were sunk and galleries driven into chalk and limestone deposits to mine the prized flint.

Crude mining tools consisted of rough picks and hammers of flint, and pointed stone with handles of stag horns. Picks of red deer antlers were used to loosen chunks of flint. Shovels were made from the shoulder blades of animals. Fire-setting was used to loosen up a working face of flint.

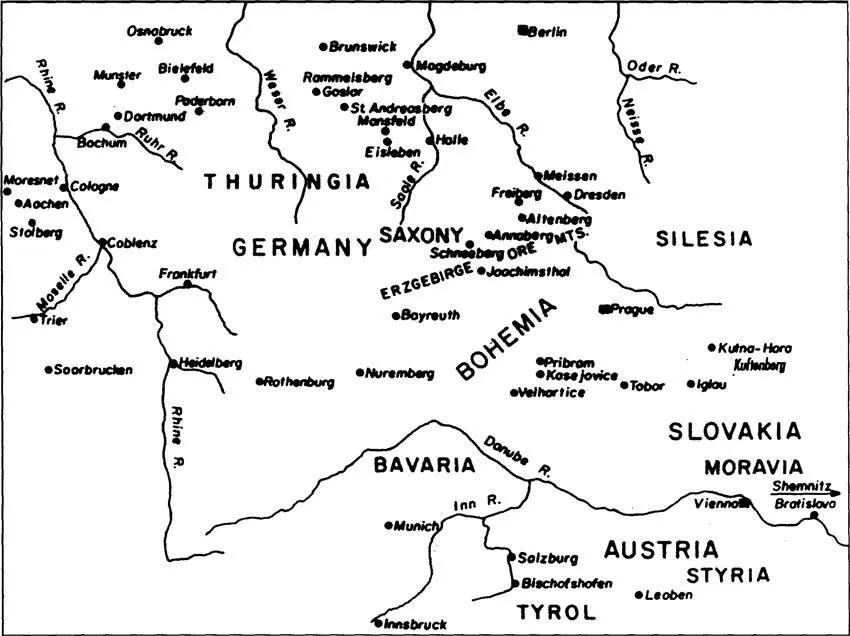

As Neolithic man turned to agriculture, his diet came to include more grains and vegetables and less meat protein. Salt became a necessity of life, both as a food and for religious ceremonies. Cakes of salt were later used as money (currency), hence the term “salary”. Ochres and amber were employed for decorative purposes. In this way, salt, amber, ochres and good quality flints became increasingly important objects of trade. Most of the salt was mined in what is now known as Austria, at Hallstatt, near Salzburg (see Figure 2). Amber was found on the shores of the Baltic Sea.

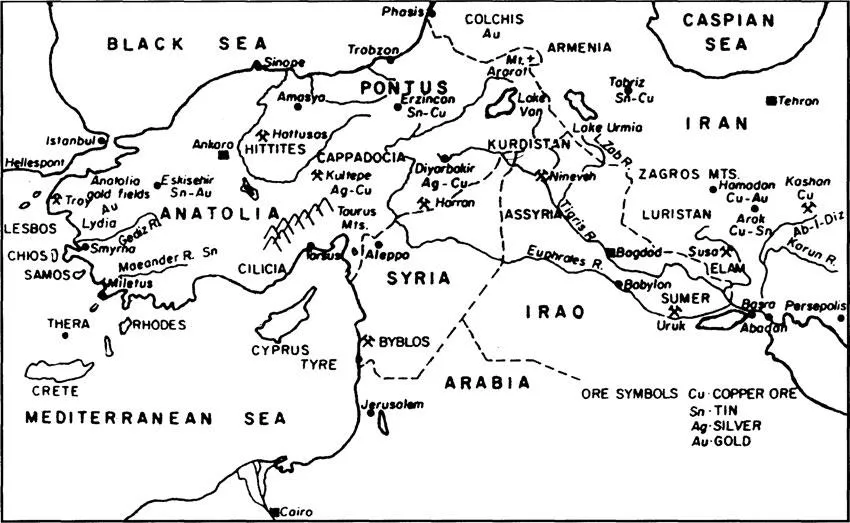

Meanwhile, the Middle East had become the known world’s bread basket in those days. The extremely fertile land of Mesopotamia (in the river valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates) produced most of the food, where there was a warmer climate with longer growing seasons. This was probably the biblical “Garden of Eden”. Farming became highly advanced in this area.

It was natural that great trade routes should become established between western Europe and the Middle East and beyond during this period. These trade routes passed through Mesopotamia. Trade was effected with flint, salt, amber, bitumen, pottery and agricultural products; and much later with ivory, spices, gold and other metals. Even though France had the best deposits of flint, the greatest developments in civilised advancement during this Neolithic period occurred in the Middle East: in Mesopotamia, Persia (Iran), Media (Iraq) and Arabia (Saudi Arabia, Syria and Jordan) (see Figure 3).

Although flint and other stones had become the raw materials for fashioning tools, implements and weapons, and haematitic ochres had been used in the powder form for decorative and funerary purposes, the use of metals was to follow later. The first metal to attract man’s attention (before 6000 BC) was gold. Gold was first found glittering in streambeds or water holes as placer (alluvial) gold, and sometimes as free native gold in shallow rock outcrops. Gold naturally collects in stream deposits because when pure it is 19.3 times heavier than water. But gold was found to be too soft for use as a tool or implement. Instead, it was valued for its great charm, its enduring untarnishable yellow glitter and its great malleability and ductility.

The purity, or fineness, of gold is expressed as the number of parts per thousand of pure gold in an alloy, or in terms of carats. Pure gold is 1,000 fine or of 24-carat value. When pure and uncontaminated with silver and other metals, it can be hammered into very thin sheets (gold leaf) in an art known to the ancients as “gold beating”. Gold can be beaten to a thickness of 0.00001 mm when pure, or drawn from a single gram to a length of about 3 km. When beaten to about 0.00025 mm, it is used to cover the domes of public buildings, such as the Albert Memorial (London), many state capitols in the United States, and in the Grand Place of Brussels. It is highly regarded for this purpose, not only for its excellent decorative effect, but for its great resistance to atmospheric weathering. As an internal decoration, countless works of art have been gilded with gold leaf, as in many of the cathedrals, museums and palaces of Europe and South America. From earliest times, gold was highly prized by monarchs, and any gold found became the property of the kingdom.

One of the most fabulous collections of gold ornaments is now held by the famous Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. This particular collection represents some of the finest works of the goldsmith’s art ever created. The little-known race of marauding warriors, the Scythians, had apparently commissioned artisans from other lands to craft these objects. This work was done between 800 and 400 BC with gold won from the Altai Mountains in Siberia.

Because of its high ductility, gold wire can be used for making gold lace. It can also be woven with silk threads into a cloth known as “cloth of gold”, which is highly prized for ceremonial trappings a...