eBook - ePub

How to Make Trouble and Influence People

Pranks, Protests, Graffiti & Political Mischief-Making from across Australia

Iain McIntyre

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 320 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

How to Make Trouble and Influence People

Pranks, Protests, Graffiti & Political Mischief-Making from across Australia

Iain McIntyre

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

This book reveals Australia's radical past through more than 500 tales of Indigenous resistance, convict revolts and escapes, picket line hijinks, student occupations, creative direct action, street art, media pranks, urban interventions, squatting, blockades, banner drops, guerilla theatre, and billboard liberation. Twelve key Australian activists and pranksters are interviewed regarding their opposition to racism, nuclear power, war, economic exploitation, and religious conservatism via humor and creativity. Featuring more than 300 spectacular images How to Make Trouble and Influence People is an inspiring, and at times hilarious, record of resistance that will appeal to readers everywhere.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist How to Make Trouble and Influence People als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu How to Make Trouble and Influence People von Iain McIntyre im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Política y relaciones internacionales & Defensa política. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Detail from “Smash Uranium Police States” poster created at the height of anti-uranium movement in 1978 by Michael Callaghan. Courtesy of Jura Books collection.

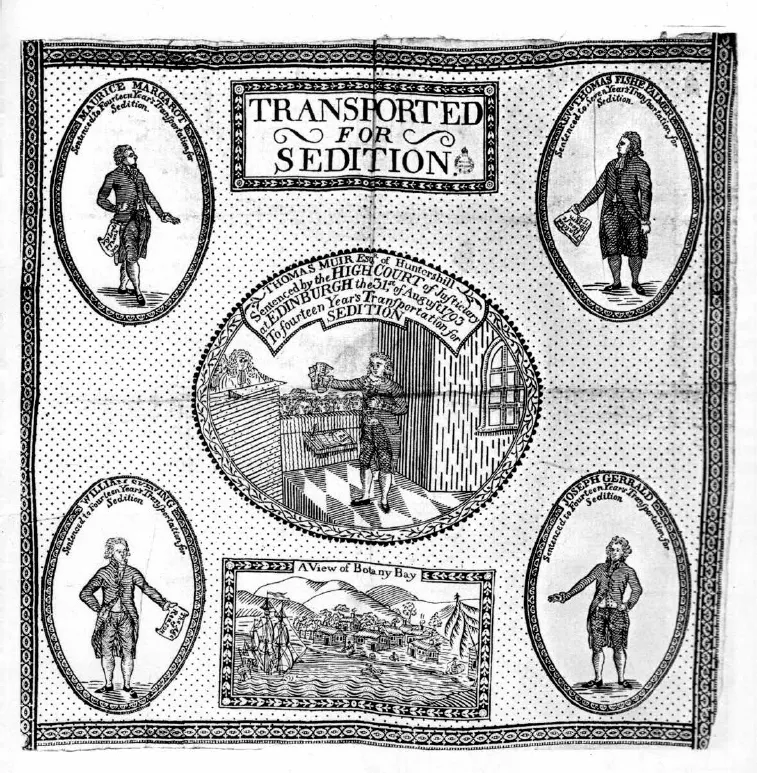

Graphic depicting the Scottish Martyrs who were exiled to Australia for their part in advocating democratic reform. Artist unknown.

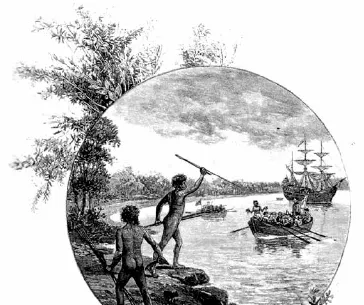

Gweagal people opposing the arrival of Captain James Cook in 1770. Engraving from Australia: The First Hundred Years, by Andrew Garran, 1886

1788-1849

Prior to the British invasion of 1788 the Australian continent had been occupied by Indigenous peoples for at least 42,000, if not 150,000 years. Living a largely nomadic lifestyle, involving gradual modification of their ecosystems through fire and selective hunting and gathering, Indigenous Australians’ cultural forms and customs varied widely. Regardless of this divergence all emphasised a deep connection to the land and the intrinsic place of humans within it.

Outside of the Torres Strait Islands, which are situated between Cape York Peninsula, QLD and Papua New Guinea, most of the hundreds of Indigenous language groups and nations were organised in relatively non-hierarchal ways with power decentralised rather than centred in the hands of a few. Conflict between different communities occurred, but permanent standing armies were unknown and the annihilation of rival populations did not occur.

The first contacts with Europeans occurred from the Seventeenth Century as firstly Dutch, and then French and British, explorers and traders sought new territories to document and conquer. Most of these interactions ended in conflict, or with the local population fleeing their intruders.

Following Captain Cook’s mapping of the Northern and Eastern coastlines in 1770, the British decided to set up a colony at Botany Bay in 1788. This decision was motivated by a number of factors, the most commonly cited of which was the need to establish a new penal colony in the wake of the American Revolution. The increasing urbanisation of the British populace and the impoverishment that followed the enclosure of lands, as society moved from feudalism to industrialisation, had generated major social dislocation. Minor property crimes, let alone political agitation, were dealt with harshly and, with many courts becoming less inclined to dish out the death penalty, Britain’s jails and prison hulks were overflowing.

During the first eight decades of their existence the Australian colonies played host to around 160,000 convicts, 26,500 imported directly from Ireland. The decision to occupy Australia was, however, driven by more than the need to dump excess proletarians. Britain was engaged in fierce competition with the other European powers and felt the need to get in first, not least because a new colony at the bottom of the Pacific would provide a base for trade routes and naval supplies.

British law stipulated that negotiations should be entered into with the Indigenous owners of the lands they planned to annexe, but in the case of Australia the fiction of “terra nullias” was employed to void such obligations. Under this concept it was decreed that Australia was an “empty” land populated by people whose lack of European-style agriculture meant they lived only on the coast and lacked ties to any particular place. This falsehood was adhered to for the following 204 years, even though once invasion had taken place it became rapidly apparent that Indigenous groups lived in every part of the country and exerted strong claims to it. As a result Indigenous sovereignty has never been ceded and Australia remains without a treaty.

Due to the size of the continent, the colonisation of Australia took quite some time with some Indigenous peoples maintaining their traditional lifestyle into the 1960s. The initial invasion of new territories generally began with coastal enclaves. Although friction was evident, these small settlements, such as the first set up at Port Jackson (Botany Bay having proved unsuitable), were generally able to live in peace with Indigenous locals as the colonists engaged in trade and had a limited impact on the ecosystem.

Once these outposts began to expand conflict became inevitable, as Indigenous people were denied access to their lands, and the native plants and animals they relied upon were displaced by farms and stock runs. Many settlers on the frontier, some of which were dubbed “squatters” as they seized land before colonial permission had been granted, also engaged in raids of extermination and the use of poison. The occupation of sacred sites and disruption to traditional travel and customs further strained relations.

The level of Indigenous resistance which met British expansion varied according to factors such as the degree to which resident populations had been decimated by newly introduced diseases, the ability of colonial powers to deploy troopers and police in support of settlers, and the level of unity amongst Indigenous locals. The existing knowledge and capability of groups to engage in warfare and the nature of the country being fought in were also important.

Indigenous opposition creatively adapted customary forms of battle to suit new situations. As semi-nomadic peoples lacking a permanent military caste Indigenous Australians were unable to unite into large scale armies capable of carrying out conventional warfare, as had occurred in other British dominions. As a result resistance took place reactively region by region with guerrilla attacks focused upon individual farms and colonists. These involved the killing of some settlers, but primarily focused on the destruction and capture of tools, crops and stock to sustain Indigenous populations and bankrupt their opponents.

Reprisals by British authorities and settlers were sometimes limited to the warriors involved, but were generally indiscriminate. As Britain had annexed the island, Indigenous Australians were technically British citizens, but legal protections were rarely extended to them. Generally charges brought against those carrying out massacres were dismissed, either for lack of anyone left or willing to provide evidence or because, unable to swear an oath on the Bible, Indigenous people were not allowed to act as witnesses. Following the occasional case where settlers or soldiers were punished their fellow colonists became careful to ensure that no documentation or proof of their actions remained.

As the colonies became more established, and police forces were founded, the use of soldiers was phased out. From the 1840s onwards frontier police were increasingly backed by the use of “Native Troopers”. These Indigenous collaborators were generally recruited from groups who had no connection, or were hostile, to those being suppressed. The use of these people’s knowledge of the bush and language became invaluable with Indigenous police carrying out most of the punitive operations in parts of Queensland.

The ability of Britain to project its military power had seen it defeat Indigenous peoples almost everywhere it had invaded and Australia proved to no exception. In some cases resistance limited expansion for decades and massacres carried out by Europeans continued into the 1920s. However by the 1850s significant coastal areas had already come under colonial control. As military resistance was progressively broken Indigenous opposition took more covert forms, primarily involving a simple willingness to survive physically and culturally.

A second main source of resistance to British authority came from those the colony was ostensibly founded to imprison. The quality of convict life over the decades varied greatly depending on broad factors such as trends in British policy, the attitude of local authorities and the state of the colonial economy. At an individual level, influences included where and to whom a convict was assigned, their possession of marketable skills, and their ability to abide by the law (or bend it successfully). As a result, whilst many transportees were brutally mistreated, particularly in places of secondary punishment such as Moreton Bay, others enjoyed opportunities they could never have dreamed of back in Britain. Once paroled, enterprising ex-convicts set themselves up as merchants or joined free settlers in stealing land from the locals, some founding dynasties that dominated colonial politics for decades.

Such opportunities did not exist for all however, and exploitation and maltreatment inevitably led to conflict. Other than generating resistance by dint of their position as bottom dogs in colonial society, a number of convicts were predisposed to rebellion due to their involvement in Irish uprisings as well as trade union and democratic movements. Most chose to resist furtively by feigning stupidity, pilfering, “losing” tools, and working slowly and inefficiently. Many asserted their humanity by engaging in relationships, same-sex and otherwise, proscribed by law. Occasionally opposition became more overt with strikes, rebellions and escapes. From the 1820s onwards, when Britain instituted a harsher regime for convicts, some also engaged in social banditry as increasing numbers of prisoners “bolted” to become bushranging outlaws.

A boom in the price of wool, tied to the Industrial Revolution, saw a major expansion in the colonies with new settlements founded in the 1820s and 1830s. WA and Queensland began as outposts, Victoria came about through largely unplanned and often illegal land grabs, and SA was set up as a convict-free planned settlement. Van Diemen’s Land, known as Tasmania from the 1850s onwards, had first been invaded in 1803 and became a separate colony in 1825.

As this expansion took place a number of non-convict immigrants, freed convicts and Australian-born colonists involved in “free labour” began to agitate around the issues affecting them. Coming up against draconian laws and exploitation by employers, skilled workers – including shipwrights, cabinet makers, and typographers – combined into small societies from the late 1820s onwards. These attempts at organisation, and the occasional strike action they undertook, were often undermined by the authorities’ use of convicts. When this was coupled with an economic depression during the 1840s, caused by what would become a familiar pattern of a speculat...