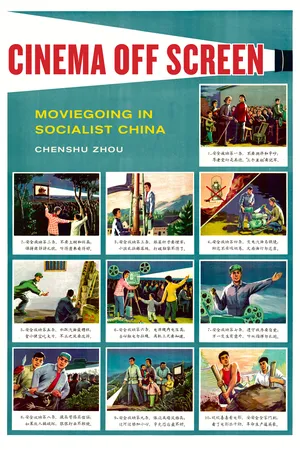

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Space

“Film is the most important of all arts.” Attributed to Lenin, this slogan was reportedly posted in movie theaters across China. It is hard to say if film was in fact more important than literature, theater, and other visual arts to the CCP. But party investment in film production and exhibition began early on. While based in Yan’an, a remote town in Shaanxi Province, during the War of Resistance against Japan (1937–1945), the CCP began its initial foray into cinema with the creation of the Yan’an Film Group (yan’an dianying tuan) in 1938. As part of the General Political Department of the Eighth Route Army, the Yan’an Film Group shot documentary films and managed three projection teams. In 1946, during the Civil War (1945–1949) with the Guomindang, the CCP founded its first film studio, the Northeast Film Studio, which was followed by the establishment of the Beijing Film Studio and Shanghai Film Studio in 1949. The Central Film Bureau came into being under the party’s Central Propaganda Department in February of the same year and then became part of the Ministry of Culture in October. The bureau would remain the official government organ that oversaw the production, distribution, and exhibition of films, around which what Yingjin Zhang calls a “sprawling bureaucracy” took shape.1 Another key player in the system was China Film Corporation (zhongying gongsi). Founded in February 1951, it was the central agency overseeing all film distribution in China. Despite minor institutional changes, the overall distribution mechanism remained largely the same over the next five decades: the China Film Corporation purchased film copies from state-owned film studios for a flat rate, shielding the studios from both market pressure and incentives; it then distributed the films to its regional branches, which rented copies to various exhibition outlets.

As the end point of a film’s life cycle, exhibition was the interface between the nascent socialist film industry and its audience. In the first years of the PRC, there was a consensus among both high-level administrators and exhibitors on the ground that a new nation required not only new films and new aesthetics but also new kinds of spaces to show these films. They treated exhibition space not as a neutral background to other objects of attention, but a semiotic field that actively interpellated viewers—in other words, an interface that carried its own message. This chapter provides a historical overview of the socialist framework of film exhibition by showing how the state and its agents at the grassroots level purposefully tried to find and produce the “right” exhibition space. Two intertwined processes were involved: the expansion of film exhibition from commercial movie theaters in urban centers to communal spaces in work units, rural areas, and military camps, and the active inscription of the exhibition space as a communication interface. Most of the chapter focuses on the early socialist period or the Seventeen Years, during which both processes were guided by the cardinal principle of “serving workers, peasants, and soldiers.” A brief discussion of new developments in the 1980s is also included, showing how ideological shifts at a time of transition were reflected in the spatial configurations of film exhibition.

MOVIEGOING IN “OLD CHINA”

When the CCP seized control of existing film infrastructures from the Guomindang, films had been shown and produced in China for half a century. Although the domestic film industry that grew large during the Republican era (1911–1949) was influenced by diverse interests, practices, and audiences, the dominant post-49 narrative portrayed film culture of the “old society” as commercial, bourgeois, capitalist, and imperialist. In A History of the Development of Chinese Cinema (Zhongguo dianying fazhanshi), a canonical text first published in 1963, Cheng Jihua summarizes that after being introduced to China as “a novel plaything,” cinema has been “a tool used by imperialist countries to achieve both the economic and cultural invasions of China.” Except for a small number of films that reflected the pursuits of capitalist democratic culture, Republican cinema, for Cheng and many others, embodied the “semi-colonial and semi-feudal” nature of Chinese society.2

Such a characterization of pre-49 Chinese cinema is not entirely without basis. Cinema was indeed imported as a commodity for entertainment. Some of the earliest venues for exhibiting films in China around 1900 were teahouses and amusement gardens, where cinema was shown as a novelty among other attractions such as magic shows, traditional opera performances, fireworks, and displays of antiques and rare flowers.3 In the first decade of the twentieth century, film exhibition began moving into purposely built movie theaters. Cities including Harbin, Jinan, Kunming, Guangzhou, Wuhan, Beijing, Tianjin, and Shanghai all reportedly had their first dedicated movie theaters built by 1910.4 Domestic film production began around the same time, allegedly first in Beijing and then in Shanghai.5 Early short films offered entertainment to a growing urban audience with genres such as slapstick comedies, urban sceneries, and current affairs. As long narrative films became more standard, crime, romance, martial arts (wuxia), and the supernatural (shenguai) emerged as some of the most popular genres until the Guomindang government passed the Film Censorship Law (dianying jiancha fa) in 1930, tightening censorship of content deemed superstitious, immoral, or unpatriotic. Although the 1930s saw the emergence of leftist films, working out of Shanghai—the center of Chinese film industry at the time, socially conscious filmmakers had to negotiate their political vision with commercial demands.6

What Chinese filmmakers also faced was a film culture that remained heavily Westernized. Although domestic films gradually gained more market share in the 1930s and in the few years after the beginning of World War II, foreign imports, especially Hollywood films, dominated the Chinese market for most of the time before 1949. Some first-run theaters exclusively showed foreign films, which were considered superior to domestic productions. Movie theaters were also Westernized places. In Shanghai, most of the movie theaters built between the 1910s and 1949 had Western-sounding names, such as Empire (Enpaiya, opened in 1921), Carlton (Ka’erdeng, 1923), and Odeon (Audi’an, 1924).7 Aspiring to be like movie palaces in Europe and America, many theaters built in the 1920s and ’30s boasted grandiose façades, Western architecture and equipment, large seating capacity, comfortable sofa-chairs, air-conditioning, and luxurious interiors. The famous Grand Theater (Daguangming yingxiyuan)—first opened in 1928 and remodeled in 1933—featured architecture that was so impressive that the Chinese press gave it the title of “the only grand architecture in the Far East.”8 Nanking Theater (Nanjing daxiyuan), which opened on March 25, 1930, reportedly had an interior modeled after the Italian renaissance style with bricks imported from Britain and expensive fabric decorating the whole place.9 Spatial design within the movie theater and services provided to customers also betrayed Western influences. In luxurious first-or-second-run theaters, signage was often in English; it was standard to have smoke rooms for the gentlemen and makeup rooms for the ladies; theaters also employed non-Chinese ushers to further boost their prestige.10

All that was deemed desirable about a movie theater became reasons for denouncing the Republican film culture after 1949. Take the Roxy Theater as an example. When the Roxy Theater opened in Shanghai in December 1939, its opening announcement touted it as the pinnacle of progress: “In Shanghai today, population density has reached the highest level. It has become obvious that the city needs the most scientific, most up-to-date modern movie palace. By rebuilding on the site of the former Olympia Theater, the Roxy stands at the forefront of the new age.”11 With an exclusive contract with the Hollywood studio MGM, the Roxy Theater was seen as the “epitome of the glamour, sophistication, and cosmopolitanism of modern urban life.”12 By 1951, an article in Mass Cinema describes the theater in completely changed terms: “No one in Shanghai did not know about the Roxy Theater. But before ‘liberation,’ very few people had the right to enter the theater. It was because its entry fee was too high, which was also why it was famous. This theater was initially established by a Chinese person with the surname Pan, but . . . it exclusively served imperialists. Hence English was spoken in the theater and English signs were everywhere.”13 Attacking the old Roxy on the grounds of class and foreign connections, this passage exemplifies the dominant CCP criticism of pre-49 Chinese cinema. Such criticism deliberately overlooked the Republican history of education cinema, which actually provided precedents for many of the practices of socialist film exhibition (see chapter 3), so that the stage could be set for the new regime as the harbinger of radical change, a revolutionary that would rid China of “harmful” capitalist culture that dominated the “old society.” But what principles should the “new society” adopt for its cultural production and consumption? In Western discourses, the new socialist logic is often dismissed as “propaganda.” The label is not unjustly applied; in fact, the CCP never shied away from publicly acknowledging cinema as “an instrument of propaganda” (xuanchuan gongju). But merely calling socialist culture “propaganda” does not tell us much about how it worked, what messages it tried to convey, and what forms or mediums it employed to convey those messages. I will instead turn to the notion of “serving workers, peasants, and soldiers,” which was first advanced by Mao Zedong in his 1942 “Talks at the Yan’an Forum of Literature and Arts” (“Talks” hereafter). Following the principle of “serving workers, peasants, soldiers,” film exhibition was reorganized not just as an institution of propaganda, but to serve the goals of both political education and mass entertainment.

BETWEEN MASS CULTURE, EDUCATION, AND PROPAGANDA

In May 1942, a forum on literature and arts was held in Yan’an, in which Mao gave speeches at two separate meetings, which became known as “Talks at the Yan’an Forum of Literature and Arts.” At the All-China Congress of Literary and Arts Workers, held in Beijing in July 1949, Zhou Yang (1908–1989), a prominent literary theorist who also held multiple high-level positions within the CCP cultural establishments, declared that the artistic direction laid down by Mao’s “Talks” would be the only correct direction for literature and arts in the new regime, namely, that literature and art should serve the masses, especially workers, peasants, and soldiers.14

Frequently evoked by artists, critics, and party authorities, the mandate of “serving workers, peasants, and soldiers” was not as straightforward as it first seemed. On one hand, the “Talks” demanded that literature and art be subordinate to politics. Against the backdrop of the War of Resistance against Japan, Mao called on writers and artists to be a cultural army in the revolutionary machinery (“we must also have a cultural army, which is absolutely indispensable for uniting our own ranks and defeating the enemy”15). It follows that political criteria should always take priority over artistic criteria in the evaluation of art. In Ban Wang’s view, it was this interpretation of the “Yan’an principle” that led many in the West to dismiss Communist art as mere propaganda lacking aesthetic value.16 On the other hand, the “Talks” has also been seen as the culmination of a trend toward popularization in literature and art since the 1920s. The expectation that Mao had for writers and artists was to produce works welcomed by the worker-peasant-soldier masses. Recent studies of Maoist culture have increasingly called attention to the link between the “Talks” and popular culture. Barbara Mittler sees “serve the people” as an ideology that demands propaganda art to be popular.17 Krista Van Fleit Hang argues that according to “Talks,” providing accessible entertainment to the masses is a task of equal importance to the education of the masses, which Mao describes respectively as “popularization” (puji) and “elevation” (tigao).18

I agree with Van Fleit Hang that the “Talks” advances not one, but two imperatives for writers and artists. But how should mass entertainment and education relate to each other? It is important to note that the “Talks” did not view entertainment and education as separate goals, but as different stages in the same dialectical process known as the “mass line” (qunzhong luxian). The “mass line” policy required leadership to be “from the masses to the masses.” For literary and artistic workers, it meant that they “must serve the people with great enthusiasm and devotion, and they must link themselves with the masses, not divorce themselves from the masses.”19 In David Holm’s words, writers and artists were instructed to “massify” themselves by gaining “a first-hand knowledge and sympathetic understanding of the local worker, peasant and soldier audiences.”20

The purpose of getting to know the masses, however, is not just to create works that appeal to them. After being the pupils, writers and artists are supposed to become the teachers of the masses. The notion of “the people” in Maoist discourse is an ambivalent one. According to Maurice Meisner, Mao identifies “the people” primarily with the peasantry and attributes to them an almost inherent revolutionary spirit.21 In the “Talks,” “the people” are the object of lavish praise. Talking about his own transformation as a youth, Mao opposes workers and peasants against intellectuals. Initially, as a student himself, he thought intellectuals were clean, whereas workers and peasants were filthy. After he joined the revolution, his perception was reversed. Unreformed intellectuals became in his eyes the filthy ones. Despite the dirt and feces on their bodies, workers and peasants were in fact clean. Showing how the young Mao progressed from su...