![]()

PART ONE

![]()

CHAPTER 1

I’M LYING ON the floor watching, against my will, a bad actress in a drug commercial tell me about her fake pain.

“Just because my pain is invisible,” she pleads to the camera, “doesn’t mean it isn’t real.” And then she attempts a face of what I presume to be her invisible suffering. Her brow furrows as though she’s about to take a difficult shit or else have a furious but forgettable orgasm. Her mouth is a thin grimace. Her dim eyes attempt to accuse something vague in the distance, a god perhaps. Her bloodless complexion is convincing, though they probably achieved this with makeup and lighting. You can do a lot with makeup and lighting, I have learned.

Now I watch her rub her shoulder where this invisible pain supposedly lives. Her face says that clearly her rubbing has done nothing. Her pain is still there, of course, deep, deep inside her. And then I am shown how deep, I am shown her supposed insides. A see-through human body appears on my laptop screen showcasing a central nervous system that looks like a network of angry red webs. The webs blink on and off like Christmas lights because the nerves are overactive, apparently. This is why she suffers so. Now the camera cuts back to the woman. Gray-faced. Hunched in the front yard of her suburban home. Her blond children clamber around her like little jumping demons. They are oblivious to her suffering, to the red webs inside of her. She looks imploringly at the camera, at me really, for this is a targeted ad based on all of my web searches, based on my keywords, the ones I typed into Google in the days when I was still diagnosing myself. She looks withered but desperate, pleading. She wants something from me. She is asking me to believe her about her pain.

I don’t, of course.

I lie here on my back on the roughly carpeted floor with my legs in the air at a right angle from my body. My calves rest on my office chair seat, feet dangling over the edge. One hand on my heart, the other on my diaphragm. Cigarette in my mouth. Snow blows onto my face from an open window above me that I’m unable to close. Lying like this will supposedly help decompress my spine and let the muscles in my right leg unclench. Help the fist behind my knee to go slack so that when I stand up I’ll be able to straighten my leg and not hobble around like Richard III. This is a position that, according to Mark, I can supposedly go into for relief, self-care, a time-out from life. I think of Mark. Mark of the dry needles, Mark of the scraping silver tools, his handsome bro face a wall of certainty framed by a crew cut. Ever nodding at my various complaints as though they are all part of a grand upward journey that we are taking together, Mark and I.

I lie like this, and I do not feel relief. Left hip down to the knee still on vague fire. A fist in my mid-back that won’t unclench. Right leg is concrete all the way to my foot, which, even though it’s in the air, is still screaming as if crushed by some terrible weight. I picture the leg of a chair pressing onto my foot. A chair being sat on by a very fat man. The fat man is a sadist. He is smiling at me. His smile says, I shall sit here forever. Here with you on the third floor of this dubious college where you are dubiously employed. Theater Studies, aka one of two sad concrete rooms in the English department. Your “office,” I presume? Rather shabby.

Downstairs, in the sorry excuse for a theater, they’re waiting for me.

Where is Ms. Fitch already?

She should be here by now, shouldn’t she?

Rehearsals begin, well, now.

Maybe she’s sick or something.

Maybe she’s drunk or on drugs or something.

Maybe she went insane.

I picture them, my students, sitting on the stage. Swinging long, pliant legs over the edge. Young faces glowing with health as though they were spawned by the sun itself. Waiting for my misshapen body to hobble through the double doors. Quietly cursing my name as we speak. About to declare mutiny, any minute now. But not so long as I lie here, staring at this drug-commercial woman’s believe-me-about-my-pain face. A face I myself have made before a number of people. Men in white lab coats with fat, dead-eyed nurses hovering silently behind them. Men in blue polo shirts who are ever ready to play me the cartoon again about pain being in the brain. Men in blue scrubs who have injected shots into my spine and who have access to Valium. Bambi-ish medical assistants who have diligently taken my case history with ballpoint pens but then eventually dropped their pens as I kept talking and talking, their big eyes going blank as they got lost in the dark woods of my story.

“For a long time, I had no hope,” the woman in the drug commercial says now. “But then my doctor prescribed me Eradica.”

And then on the screen, there appears a cylindrical pill backlit by a wondrous white light. The pill is half the yellow of fast-food America, half the institutional blue of a physical therapist’s polo shirt. I believe it would help you, my physiatrist once said of this very drug, his student/scribe typing our conversation into a laptop in a corner, looking up at me now and then with fear. I was standing up because I couldn’t physically sit at the time, hovering over both of them like a wind-warped tree. I still have a sample pack of the drug somewhere in my underwear drawer amid the thongs and lacy tights I don’t wear anymore because I am dead on the inside.

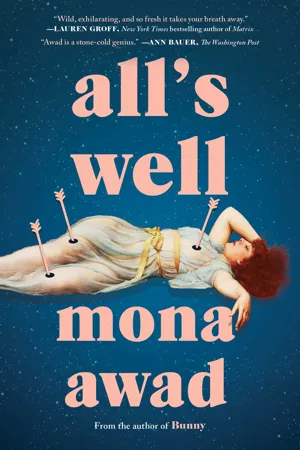

Now I attempt to hit the play button in the bottom left corner of the YouTube screen, to skip past this hideous ad to the video I actually want to watch. Act One, Scene One of All’s Well That Ends Well, the play we are staging this term. Helen’s crucial soliloquy.

Nothing. Still the image of the blue-and-yellow pill suspended in midair, spinning.

Your video will play after ad, it reads in a small box in the bottom corner of the screen. No choice. No choice then but to lie here and listen to how there is hope thanks to Eradica. The one pill I didn’t try, because the side effects scared me more than the pain. No choice but to watch the bad actress bicycle in the idyllic afternoon of the drug commercial with a blandly handsome man who I presume is her fake husband. He is dressed in a reassuring plaid. He reminds me of the male torso on the Brawny paper towels I buy out of wilted lust. Also of my ex-husband, Paul. Except that this man is smiling at his fake wife. Not shaking his head. Not saying, Miranda, I’m at a loss.

Knock, knock at my door. “Miranda?”

I take a drag of my cigarette. Date night now, apparently, in the drug commercial. The actress and fake hubby are having dinner at a candlelit restaurant. Oysters on the half shell to celebrate her return from the land of the dead. Toasting her new wellness with flutes of champagne, even though alcohol is absolutely forbidden on this drug. He gets up from the table, holds out his hand, appearing to ask her to dance. She is overcome with emotion. Tears glint in her eyes as she accepts. And then this woman is dancing, actually dancing with her husband at some sort of discotheque that only exists in the world of the drug commercial. We don’t hear the sound of the music at the discotheque. The viewer (me) is invited to insert their own music while “some blood cancers” and “kidney failure” are enumerated as side effects by an invisible, whitewashed voice that is godly, lulling, beyond good and evil, stripped of any moral compunction, that simply is.

“Miranda, are you there? Time for rehearsal.”

Watching the actress’s merriment in the discotheque is embarrassing for me. As a drama teacher, as a director. And yet, watching her rock around with her fake husband, wearing her fake smile, her fake pain supposedly gone now, I ask myself, When was the last time you danced?

Knock, knock. “Miranda, we really should get going downstairs.”

A pause, a huff. And then I hear the footsteps fall mercifully away.

Now it is evening in the world of the drug commercial. Another evening, not date night. Sunday evening, it looks like, a family day. The bad actress is sitting in a nylon tent with the fake children she has somehow been able to bear despite her maligned nervous system, her cobwebby womb. Hubby is there too with his Brawny torso and his Colgate grin. He was always there, his smile says. Waiting for her to come back to life. Waiting for her to resume a more human shape. What a hero of a man, the drug commercial seems to suggest with lighting. And their offspring scamper around them wearing pajamas patterned with little monsters, and there are Christmas lights strung all across the ceiling of the tent like an early-modern idea of heaven. She smiles wanly at the children, at the lights. Her skin is no longer gray and crepey. It is dewy and almost human-colored. Her brow is unfurrowed. She is no longer trying to take a shit, she took it. She wears eye shadow now. There’s a rose gloss on her lips, a glowing peach on her cheeks (bronzer?) that seems to come from the inside. Even her fashion sense has mildly improved. She cares about what she wears now. For she is supposedly pain-free. LESS PAIN is actually written in glowing white script beside her face.

But I don’t believe it. It’s a lie. And I say it to the screen, I say, Liar. And yet I cry a little. Even though I do not believe her joy any more than I believed her pain. A thin, ridiculous tear spills from my eyelid corner down to my ear, where it pools hotly. The wanly smiling woman, the bad actress, has moved me in spite of myself. The fires on the left side of my lower body rage quietly on. The fist in my mid-back clenches. The fat man settles into the chair that crushes my foot. He picks up a newspaper. Checks his stock.

But at least my video, the one I’ve been waiting for—where Helen gives her soliloquy, the one where she says yes, the cosmos appears fixed but she can reverse it—is about to play.

And then just like that, my laptop screen freezes, goes black. Dead. A battery icon appears and then fades.

I picture the power cord, coiled in the black satchel sitting on top of my desk, the cord gray and worn like the snipped hair of a Fury. I contemplate the socket in the wall that is absurdly low to the floor, behind my desk. I picture getting up and hunting for the power cord, then bending down and plugging it into the socket.

I lie there. I stare at the dead laptop screen smudged by my own fingerprints.

Snow from the open window I cannot close because I cannot bend keeps falling on my face. I let it fall. I close my eyes. I smoke. I’ve learned to smoke with my eyes closed, that’s something.

I feel the wind on my face. I think: I’m dying. Death at thirty-seven.

The fat man on the chair whose leg is crushing my foot raises his glass to me. Drinking sherry, it looks like. Cheers, says his face. He is pleased. He settles deeper in. Returns to his newspaper.

I shake my head in protest. No, I whisper to the fat man, to the back of my eyelids. I want my life back. I want my life back.

“Miranda, hello? Miranda?”

A soft knock on the half-open door. And then that voice again from which I instantly recoil. The fires rise, the fists clench, the fat man looks up from his newspaper. I can hear the new age chimes in that voice twinkling. It is the voice of false comfort, affected concern, deep strategy, it is a voice I often hear in my nightmares. It is the voice of Fauve. Self-appointed musical director. Adjunct. Mine enemy.

“Miranda?” says the voice.

I don’t answer.

I feel her consider this. Perhaps she can see my feet poking out from behind the desk.

“Miranda, is that you?” she tries again.

I remain silent. So I am hiding. So what?

At last I hear her retreat. Soft footsteps pattering down the hall, away from my door. I breathe a sigh of relief.

Then another voice follows. Decisive. Brisk. But there is love in there somewhere, or so I tell myself.

“Miranda?”

“Yes?”

Grace. My colleague. My assistant director. M...