eBook - ePub

Food and Climate Change without the hot air

Change your diet: the easiest way to help save the planet

S L Bridle

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 256 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Food and Climate Change without the hot air

Change your diet: the easiest way to help save the planet

S L Bridle

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

"• 25% of greenhouse gas emissions come from food – how can we reduce this?

• What effect does the food we eat have on the environment?

• How will climate change affect the food we will eat in the future?

• Can the choices we make as consumers reduce carbon emissions dramatically?

Inspired by the author's former mentor David MacKay (Sustainable Energy without the Hot Air), Food and Climate Change is a rigorously researched discussion of how food and climate change are intimately connected. In this ground-breaking and accessible work, Prof Sarah Bridle focuses on facts rather than emotive descriptions. Highly illustrated in full colour throughout, the book explains how anyone can reduce the climate impact of their food."

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Food and Climate Change without the hot air als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Food and Climate Change without the hot air von S L Bridle im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Ciencias biológicas & Ciencia medioambiental. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

1

Chapter 1 Introduction

How much do you think the last meal you ate contributed to climate change? And which bits of it were the biggest culprits? Diets aimed at reducing environmental impact are becoming more popular, for example vegans avoid all animal products including meat, fish, cheese, milk and eggs. But does this really help, and anyway how much of a big deal is food compared to all the other contributions to climate change?

When I first learned about the impact of food on climate change I went vegan for a while. I put my jacket potato into the oven for two hours and waited around smugly with my can of beans, unpacking my suitcase after a transatlantic flight. I drove to the shop 3 km (1.86 miles) down the road just to buy some plant milk, and also probably picked up a pack of green beans flown in from another continent.

My efforts to help reduce climate change were based on little more than a gut feeling. What I really needed was detailed figures, so I could make informed decisions that would make a big difference, and that’s why I wrote this book – to get clear numbers that I could use, and share with everyone else.

Climate change

The overwhelming scientific consensus is that climate change is real, it is happening, and it needs to be addressed. There is a wealth of information available about climate change, so this book doesn’t repeat all that. There is just a short appendix at the end, summarizing the main facts (appendix “Climate change”).

However, we will address one issue that often confuses people: what’s the difference between climate change and global warming? Yes, greenhouse gases in the Earth’s atmosphere are trapping heat and cause the planet to warm up. (There’s more detail on greenhouse gases in the next section.) However, some parts of the globe are warming up faster than others. For example the continents warm up faster than the oceans. 2However, the world isn’t just getting warmer – the changing climate causes extreme weather events such as droughts, floods, and storms, sometimes affecting multiple continents (appendix “Climate change”).

So the “global” in “global warming” refers to the temperature change averaged across the whole the surface of the Earth. While it’s nice to focus on a single number, this hides a complexity that has serious consequences. Cloud, wind and rainfall patterns have an intricate dependence on variations in temperature from one geographical location to another.

This changing climate also affects food production (appendix “Impacts of climate change on food”); some farmers have already had to change what they grow. Looking ahead, crop yields and the numbers of fish caught at sea are expected to go down.

“The main way that most people will experience climate change is through the impact on food: the food they eat, the price they pay for it, and the availability and choice that they have”

– Tim Gore, Head of Policy, Advocacy and Research of Oxfam’s GROW Campaign

Greenhouse gases

We humans release a range of gases into the atmosphere. The most important of these that contribute to global warming are carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide.1 The best known of these is carbon dioxide (CO2), which is released by burning fossil fuels – in cars, aeroplanes, heating and to generate electricity.

When plants rot in a damp place they turn into methane, which is how natural gas (which is a “fossil fuel”) was made in the first place (appendix “Climate change”). In addition, about one twentieth of all the calories eaten by a cow are burped out again as methane (chapter 4). Because of the amount of food we’re producing to feed the world, and because we’re producing fossil fuels, the amount of methane in the atmosphere is increasing. When it first enters the atmosphere, 1 gram of methane causes more warming than 80 grams of carbon dioxide, but it only lasts for about 10 years before turning into carbon dioxide, so the total heat-trapping effect is equivalent to about 28 grams of carbon dioxide over a 100-year period. Have you ever inhaled laughing gas (another name for nitrous oxide)? I had nitrous oxide as a painkiller when I was giving birth – it made the pain seem less important, but I don’t remember laughing! One gram of nitrous oxide causes a similar global warming effect to about 270 grams of carbon dioxide.

The amount of nitrous oxide in the atmosphere is increasing 3because we’re feeding our crops with nitrogen fertilizers (box 2.1), and because nitrous oxide is released from animal manure (chapter 4).

For the rest of this book we will talk about “greenhouse-gas emissions” to refer to the combined effect of all the greenhouse gases. We will describe emissions in grams of carbon dioxide equivalent (written as “gCO2e” in the scientific literature) which means the amount of carbon dioxide that would cause the same energy input as all the greenhouse gases combined together, averaged over a one hundred year period. Therefore

- 100 grams of carbon dioxide corresponds to 100 grams of greenhouse-gas emissions

- 4 grams of methane corresponds to 100 grams of greenhouse-gas emissions, and

- 0.4 grams of nitrous oxide corresponds to 100 grams of greenhouse-gas emissions.

Box 1.1: Grams, kilos and precise numbers

Throughout this book we will talk about the number of grams of food consumed, as well as the number of grams of emissions. This can be written out the long way e.g. “20 grams” or in a more compact way e.g. “20 g”. When the numbers get big we sometimes switch to using kilograms (or “kilos”, for short), where one kilogram (1 kg) is the same as 1000 grams (1000 g).

To make this book easier to use and more readable, it has to be specific about the amount of greenhouse-gas emissions from different types of food. To make it easier to use the numbers we have highlighted them throughout, like this:

1 g milk = 2 g emissions

However, the actual values will depend on the specific production systems used. For example, in the case of cows’ milk it will depend on what the cow is eating and how much milk it produces. In the case of plants it will depend on the soil type (which affects the amount of fertilizer needed) and weather (which affects yield for a given amount of fertilizer).

So there is no single number, only a range of numbers for different suppliers. But we have to start somewhere. My hope is that you will start to demand the exact information from your food suppliers, so that you can make informed choices and buy from the producers who are making advances in reducing their impact on the climate. 4

How much emissions?

So where are all these greenhouse gases coming from? Fig. 1.1 shows a map of the world showing total greenhouse-gas emissions (not just food-related) for each country. On average, each world citizen causes about 24 kilos of emissions per day, but this varies greatly from one country (and person) to the next. For example, an average US citizen causes over 50 kilos of emissions per day, whereas an average citizen of most African countries causes less than 2 kilos of emission per day.

Fig. 1.1: A map of the world showing the total greenhouse-gas emissions for each country, per person per day. We are extremely grateful to the Our World In Data project for making this figure. You can find the data for this plot on their website. (URL 2)

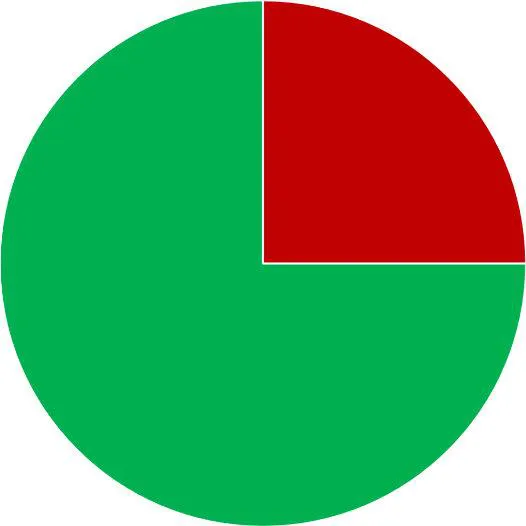

How much do you think food contributes to the total emissions? To work this out we need to add up all the greenhouse-gas emissions from all parts of the food chain. We have to include growing, clearing land, processing, manufacturing, packaging and transportation, as well as cooking the food at home and disposing of any waste. Overall, about a quarter of all global greenhouse-gas emissions come from food (Fig. 1.2). The amount of emissions from food varies from one country to the next, as does the total emissions. Food typically causes about a quarter to one third of the emissions.

Fig. 1.2: A quarter of all greenhouse-gas emissions come from food.

The amount of emissions varies greatly depending on which food is being eaten, and on the production method. For example, a steak causes more than 10 times the emissions of a portion of beans. Furthermore, the steak itself can cause 10 times the emissions again if the cow lives for 20 years instead of just 1 year (chapter 24). Fig. 1.3 shows the amount of greenhouse-gas emissions for different food categories, for the amounts of each type of food consumed in the UK. In the rest of this book we 5consider the emissions from producing each of these foods, and investigate some alternatives. But first we need to get a sense of scale.

Box 1.2: Giga/billions tons/tonnes

When we discuss large amounts of CO2 we use metric tonnes. A metric tonne is 1,000 kg by definition, and an imperial ton is 1,016 kg, so you hardly ever have to worry about the difference – it’s less than 2%). One gigatonne (1 Gt) equals one billion tonnes (giga = billion, or one thousand million).

Food emissions in perspective

On average, each person in the world ...