![]()

1.SIGNING IN AND SIGNING UP

In Artistic Creation (1901), a man at an easel sketches body parts which he magically assembles into a real woman, before frightening her off by adding a baby. Even without that resonant title, it feels like a perfect start for the story of British animation, bringing together drawing and impossible cartoon logic, topped off with a good gag. But clever though it is, the film stops short of ‘true’ animation. To make it, Walter Booth combined two important early film phenomena. In the ‘lightning sketch’ or ‘chalk talk’ – originally a music hall act – an artist rapidly sketches caricatures or other scenes on paper or blackboard. Film could enhance the ‘lightning’ aspect by cranking the camera at a slower speed during filming, thereby accelerating the drawing process when the film is projected at normal speed. ‘Stop action’ involves pausing the filming process to allow objects or people to be added, removed or replaced before filming recommences, so that when the film is projected they magically appear, disappear or transform.7

Artistic Creation (Walter Booth, 1901).

True animated films are created frame by frame, rather than captured in real time. They require a change to the internal gearing of a motion picture camera so that, at the turn of a handle or press of a button, it can take single, discrete frames rather than the usual machine-gun sequences of multiple frames per second. Where live-action cinema captures real movement in successive still photographic frames so that it can be reproduced on screen, in ‘stop motion’ animation, those fixed frames are artificially created – as drawings or using objects – so that, when run together, they create an illusion of movement that never happened in real life.8

In truth, confidently identifying Britain’s first animated film is difficult, if not impossible. Historians and researchers working on the jigsaw of early film soon discover that not just some but most of the pieces are missing. Films were bankrolled for entertainment, not posterity; there were few incentives for producers to retain film prints beyond their commercial life – if they survived that long. The cellulose nitrate stock in use until 1951 was notoriously unstable and highly flammable, and so a liability to keep around. Some prints were sacrificed for the precious silver they contained (especially during WWI); others were left to rot. By the time Britain’s national film archive arrived in 1935,9 well over half of the films made in the medium’s first 30 years were already lost.10 Catalogues, advertising and trade press can help us fill some gaps in our knowledge, though descriptions of the films may be sketchy at best. And how do we identify actual animation at a time when any kind of film was routinely described as ‘animated pictures’?

Our most reliable guide to what happened in the medium’s earliest years is what survives. For our purposes, that’s chiefly the 20-odd works preserved in the BFI National Archive which are known to have been produced before the outbreak of the First World War and in which we can observe some ‘true’ animation. A later Walter Booth film, Hand of the Artist (1906) is often claimed as Britain’s first animated film, although the surviving footage made available from the National Film and Sound Archive in Australia shows only stop action and visual effects rather than animation. But his 1907 film, The Sorcerer’s Scissors, makes several uses of actual stop motion, with a pair of magical scissors moving independently across the screen, along with a paintbrush and glue. In one scene transition, a new costume is ‘cut and pasted’ onto a character.

Sorcerer’s Scissors (Walter Booth, 1907).

One often-cited claim to what would be not be just Britain’s but the world’s earliest-known animated film can probably be safely dismissed.11 Arthur Melbourne Cooper’s Matches: An Appeal, in which an animated matchstick scrawls a plea for donations to supply matches to British troops was almost certainly not, as the filmmaker claimed in later life, made in 1899 – which would make it the world’s earliest-known animated film.12 In fact, newspaper adverts for the same appeal by the film’s sponsor, match manufacturer Bryant & May, point to a release date of late 1914, as part of a patriotic campaign in the early months of the First World War.

Dreams of Toyland (Arthur Melbourne-Cooper, 1908).

Nevertheless, Melbourne-Cooper, like Walter Booth, would be a key player in the flowering of animation between 1906 and 1908, alongside James Stuart Blackton in the USA and Emile Cohl and Segundo de Chomón in France. His Dreams of Toyland, released in 1908, is a true milestone. The film begins with live-action scenes of a boy visiting a toy shop and then being put to bed, after which the scene transforms to a model town square in which his toys are brought to life through stop-motion. This animated ‘dream sequence’ lasts almost four minutes – and would have involved manoeuvring a large cast of puppets and assorted vehicles over 3500 times around the purpose-built set.

A similar narrative framing of an animated dream sequence is found in the subsequent Tale of the Ark (1909). It’s another stop-motion marvel in which the story of Noah and his animals is ambitiously brought to life – biblical flood and all. A description of Melbourne-Cooper’s lost 1901 film, Dolly’s Toys – ‘A child dreams that toys come to life’13 – has fuelled speculation that it too may be animated film, while even stronger claims have been made for another missing film, The Old Toymaker’s Dream (1904), made by Melbourne-Cooper’s Alpha Trading Company, in which ‘An old man dreams that a toy Noah’s ark and animals grow to full size’.14

But evidence from a slightly later film – which happily survives – suggests that another trick might have been at play. Trade press hailed Walter Booth’s Dreamland Adventures (1907) as ‘a beautiful and unique Magic and Mystery Film which will enthral and captivate every audience, [in which] a party of children are accompanied through Wonders of Ocean Ice and Cloud by a Doll and a Golliwog, filled with life and characteristic animation.’15 But Booth’s toys come to life thanks not to stop motion, but to stop action and double exposure: the two inanimate dolls first appear to grow and are then replaced by actors, with outfits and make-up matching the toys’. Once full-size they can interact with the children and head off on their fantastical adventure, achieved with assorted special effects.

Booth was a former painter and amateur magician, who came to specialise in ‘trick’ films initially for Robert Paul from 1899, then on his own. Britain’s closest rival to France’s early genius of film fantasy, Georges Méliès, Booth clearly had stop-motion in his tool kit from around 1906, but used it sporadically when it suited his needs, and seems to have spared himself the effort when he could.

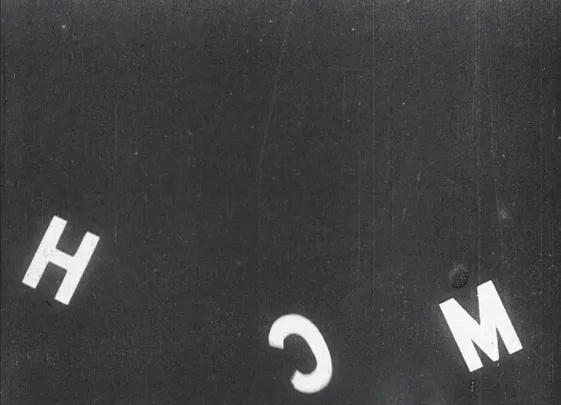

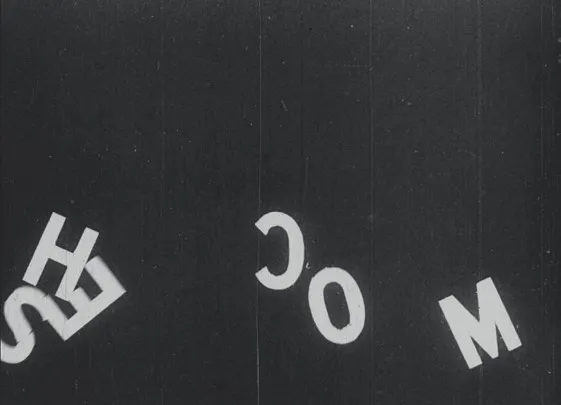

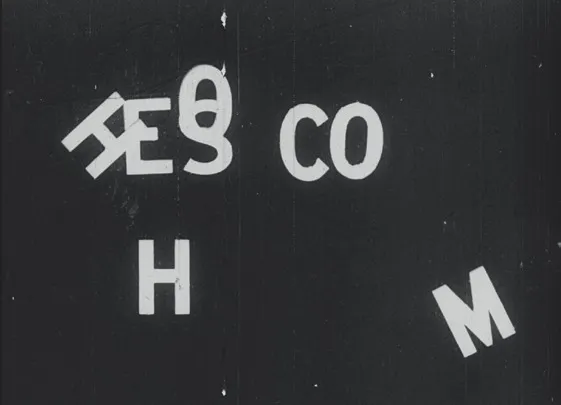

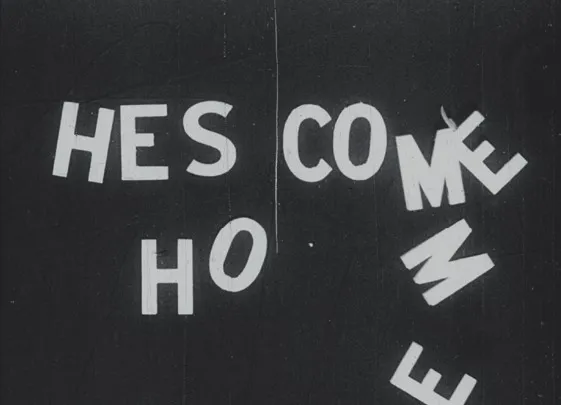

In fact, the earliest verifiable use of stop motion I have found in a British film is a sequence of animated lettering in the intertitles of a 1904 film called The Latest News – more an attractive visual flourish than a Eureka moment. The moment of discovery of animation techniques was less important than the realisation that films which found innovative uses for them could be popular. Entirely new kinds of stories and effects could be achieved by those artists prepared to invest the time and effort to work one frame at a time.

While filmmakers became more skilled in its techniques, animation had a haphazard advance in the years leading up to the First World War. Melbourne-Cooper would further his experiments with the likes of Road Hogs in Toyland (1911), a no-holds-barred, drunken, car chase thriller ‘enacted entirely by mechanical toys,’ as the main title billed it. But he continued to work in live-action filmmaking and was also a pioneer in exhibition before his career stalled around the mid-1910s.

The Latest News (Warwick Trading Company, 1904).

New players were entering the field. Charles Armstrong animated shadow puppets frame-by-frame in films like A Clown and his Donkey (1910), pioneering silhouette animation techniques later perfected by Lotte Reiniger. Nature photographer F. Percy Smith used stop motion to recreate the then-unfilmable actions of arachnids in To Demonstrate How Spiders Fly (1909). This scientific use of animation blazed new trails for the form, but Smith also appeared in trick films like Walter Booth’s Animated Cotton (1909), and is credited with the early Claymation film ...