![]()

Chapter 1

The Daguerreotype

Dickens’s Counterfeit Presentment

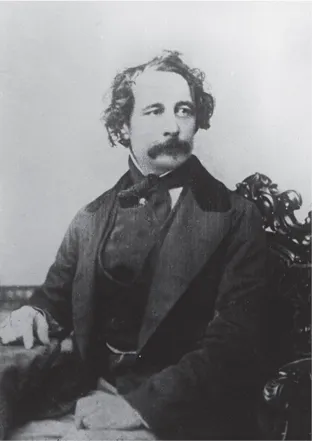

Charles Dickens was, as Joss Marsh puts it, “the most photographically famous person in Britain outside the royal family” in the nineteenth century (“Rise of Celebrity Culture” 104). He was photographed at least 120 times—an impressive number in an era when sitting for a photographic likeness was an expensive and arduous experience (Wilkins and Matz). Dickens’s photographic excess took on a notoriety of its own: for instance, an editorial in the New York Herald hyperbolically claims that by 1867 the author had posed for 500 distinct images (Kappel 170). Just as famously, Dickens was ambivalent about having his photograph taken. He first sat for a photographer in 1841, a scant two years after the public announcement of the daguerreotype and calotype processes. Sitting for a daguerreotype in Richard Beard’s studio, the first of its kind in England, Dickens found the lengthy process unpleasant and advised Miss Burdett Coutts in 1841, “If anybody should entreat you to go to the Polytechnic Institution and have a Photographic likeness done—don’t be prevailed upon, on any terms. The Sun is a great fellow in his way, but portrait painting is not his line. I speak from experience, having suffered dreadfully” (Letters 2:284). Some years later, he was asked by Herbert Fry to sit for the series Photographic Portraits of Living Celebrities, but he declined: “Nor can I have the pleasure of complying with your request. I have but just now finished sitting to a distinguished French painter, and have thoroughly made up my mind to sit no more” (Letters 8:72–73). Nevertheless, he did sit again—and again (see figure 1.1). Perhaps the next one would be more accurate, less of a counterfeit presence.

Figure 1.1. John Edwin Mayall, “Charles Dickens,” daguerreotype (c. 1855). Reproduced by permission of The Charles Dickens Museum, London.

Dickens’s response to the photographer Mayall, discussed in the introduction, illuminates several reasons for the author’s distaste of photographic portraiture: the Inimitable was concerned that these images were giving viewers a “counterfeit presentment,” or false sense of his presence, and he expressed anxiety over the idea of multiplication—the idea that his image could be reproduced again and again beyond his control. Yet he goes on to write in his letter to Mayall in October 1856, “I am not the less sensible of your valuable offer” (Letters 8:199). Indeed, photographic portraiture was quite valuable as a means of “shaping the authorial persona,” as Leon Litvack notes in his essay on the relationship between Dickens and photographer Herbert Watkins (97). Litvack describes this positive relationship with Watkins, for whom Dickens sat on several occasions and who “took the first mass-produced photographs of the novelist, thus facilitating the ownership and consumption of ‘authentic’ Dickens images by a multitude of readers and admirers, and in the process enhancing his reputation” (100). Thus Dickens’s reaction to his own portrait was complex: while on some occasions he expressed his discomfort with sitting for multiple reproducible portraits, on others he acknowledged the value of those portraits due to the increasing power of the celebrity photographic market in the mid-nineteenth century.

It is part of the coy logic of celebrity that Dickens was at times famously recalcitrant about his photographic image, while at others invested in the creation of his own celebrity. A celebrity is someone you know about but about whom you want to know more—a person in some respects available to you, yet withheld. Dickens’s resistance to his numerous photographic images cultivates just such a sense of mystery. Yet celebrity’s logic of exposure and withholding, of the abundance of the celebrity image and the elusiveness of the celebrity, does not account for the entirety of his reaction to his photographic image. As this chapter shows, Dickens’s anxiety about and interest in photography is made manifest not only in his reaction to his celebrity but in his fiction. Moreover, the figure of the negative illuminates Dickens’s particular concerns. The material photographic negative, that inverse image used to multiply photographic prints beyond the celebrity author’s control, challenges the stability of light and dark: to create a positive print using negative-based photographic technology, one must first create a negative image. An image’s inverse is thus an essential element in the reproduction of an image. This purely technical observation can be destabilizing to the idea of photographic verisimilitude. The idea that a photographic reproduction requires an inversion of light and dark challenges a centuries-old metaphoric system and calls the very nature of realistic representation into question by showing things not as they appear but as their tonal opposites.

Dickens’s desired elusiveness and the abundance of his images is mirrored through the style of realism he adopts: the profusion of detail and the concurrent elusiveness of complete verisimilitude within that detail. Developing his realist style during the time when photography began to dominate the discursive landscape, he encodes a photographic sensibility into his fictions. In this way, his fictions participate in what Christopher Rovee has described as “a different kind of photographic history from the ones we are used to reading”—a history of photography that is less about chemistry or industry, and more “a desire spelled out in words and lines that summon into presence a dead man’s touch” (388, emphasis in original). Dickens’s fictions, in other words, express a more abstract, more affective engagement with photography. Yet just as the author was uneasy with the role of photography in the construction of his celebrity image, so did the photographic qualities of his fiction demonstrate an unease with reproducibility.

Dickens’s 1859 novel, A Tale of Two Cities, is a historical novel set before the advent of photography, and as such does not directly reference any photographic technique. The novel does, however, reflect a figurative investment in photography as a means of meditating on individuality, duplication, and the past versus the present—ideas invoked through Dickens’s discussions of his celebrity photographs. In this chapter I read Tale through the lens of the daguerreotype specifically, to illustrate how this novel not only expresses a photographic sensibility but also demonstrates a working through of concerns around image multiplication made possible with negative-based photographic technologies. As discussed in the introduction, daguerreotypes have no negatives and are thus generally permanent, singular, and not reproduced. While the novel also features motifs of duplication that would align it with a more negative-based photographic logic, the logic of the daguerreotype ultimately dominates. The typical daguerreotype portrait was, as Peppino Ortoleva writes, “perceived as a portrait and at the same time as a direct projection of the person,” thought of “in terms of a presence more than a representation” (156). Daguerreotypes are also highly reflective and rely on specific lighting conditions to be viewed. Thus, the experience of viewing a daguerreotype is the experience of seeing light in two temporalities: the light of the past represented in the image and the light of the present of its viewing. This temporal duality is particularly evocative when read metaphorically alongside Dickens’s novel. The author’s critique of the past, his use of dark and light imagery, and Sydney Carton’s concluding “I see” contribute to a unified figurative system—what I read here as a photographic imagination. Yet light and dark remain unsettled and the figuration of duplication featured through Darnay and Carton is short-circuited by Carton’s death. Read in this way, the novel is photographic, but its photographic sensibility is distinctly Daguerrean.

Reading Dickens’s responses to his own celebrity image alongside Tale reinforces this logic of daguerreotypy. Both demonstrate a preference for control over the image, a resistance to the multiplication of that image, and an interest in the duality of past and present. Every daguerreotype is at once highly original, but linked to each moment it is viewed—a way out of the endless proliferation of the image made possible through negative-based technologies and yet itself a technology that emphasizes temporal duality. Dickens’s critique of the French Revolution, as we see from the novel’s opening page with its list of oppositions—best and worst, light and darkness, past and present—suggests that just as this novel will be about the past, it will also be about the present of its composition. Coupling dark and light inversion together with time, in his pithy figuration “it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness,” Dickens establishes a connection between the Enlightenment past and his own era. As Roland Barthes notes, photography can be “reality in a past state: at once the past and the real” (82). Dickens likewise thematizes the reality of the past in his historical novel, his fiction obliquely reenacting his own preoccupation with self-image and originality in the present.

Photography and the Celebrity Author

Whereas Dickens’s thematic evocation of photography in A Tale of Two Cities is anachronistic, photography was very much a present reality for him, affecting his celebrity image and thus contributing to the success of his literary works. Moreover, his concern over the circulation and control of his celebrity images parallels his more infamous preoccupation with the circulation of his literary works. Dickens was outspoken about the absence of international copyright laws and made this cause a focus of his first visit to the United States in 1842, publishing the following upon his return: “You may perhaps be aware that during my stay in America I lost no opportunity of endeavouring to awaken the public mind to a sense of the unjust and iniquitous state of the law in that country, in reference to the wholesale piracy of British works” (“International Copyright” 97). Copyright concerned Dickens, for his works were often pirated in the US press. Playing up the piracy metaphor, Dickens announced in a letter in 1842, “As to the Pirates, let them wave their black flag, and rob under it, and stab into the bargain, until the crack of doom. I should hardly be comfortable if they bought the right of blackguarding me in the Model Republic; but while they steal it, I am happy” (Letters 3:256–59, emphasis in original). In his comments about copyright, Dickens characterizes himself as a victim of relentless, unlawful trade. Aside from financial loss, the copyright issue troubles him because it means a loss of control over his work. As Tara Moore writes, “Dickens grieved over his loss of control of the physical quality of his books” in their pirated forms: “American reprints appeared with tiny type and narrow margins. For an author who carefully planned the paper quality, illustrations, and covers of his books whenever possible, as with the Christmas books, such cheap, uncontrollable printing caused pain” (280).

This well-known instance of Dickens’s response to copyright contextualizes his reaction to the circulation of his celebrity image, a circulation that, like US editions of his fiction, quickly exceeded his control. John Plunkett notes the celebrity photograph was “one of the most notable consequences of the commercialisation of photography,” with celebrity images abounding and proliferating at staggering rates. From 1860 to 1862, Plunkett writes, between three and four million copies of Queen Victoria’s cartes de visite were claimed to have been sold. In 1862 the London wholesale house Marion & Co. sold 50,000 cartes of various celebrities each month (280–81). This proliferation of images soon exceeded the control of photographers or photographic subjects, and “forgeries of the celebrity photographs became commonplace and large profits were made out of an immense number of quasi-illegal pictures” (281). A revised Copyright Bill in 1862 helped control the proliferation, but only to a certain extent.

As we have seen, Dickens was often vocal about his distaste for sitting for photographic portraits, claiming such sittings were uncomfortable, that the resulting image failed to capture his true image, and that his image was thereafter multiplied and implicitly out of his control. Paul Fox and Gil Pasternak have argued that photo portraiture “in general is instrumental in identity work,” but this does not account for how celebrity portraits were reproduced and circulated (140). Dickens was increasingly photographed, particularly after the development of the wet-plate process in 1851 reduced exposure times and made the experience less of an ordeal, and Litvack documents several instances when Dickens adopts a more favorable attitude toward the technology. On one hand, “Dickens’s dislike of the various workings of his face is well documented” (Xavier 88). Baillargeon comments that this more negative attitude “may have been intended by Dickens to reiterate his dislike for the sitting process, but it may also reflect the uneasiness with which he viewed himself in a daguerreotype, the so-called ‘mirror with a memory’ ” (4). However, in declining Mayall’s invitation Dickens uses the term “multiplication,” not just “duplication”—his concern, it seems, is not with a single daguerreotype but the idea that by this point his image was reproduced beyond his control.

This concern with a personal portrait out of control is echoed in Bleak House, which Dickens had finished three years before declining to sit for Mayall. In Bleak House, Lady Dedlock’s dignified oil portrait, part of the family gallery at Chesney Wold, is juxtaposed against the mass-produced Galaxy Gallery of British Beauty copy of this image. Regina B. Oost and Ronald R. Thomas both read Lady Dedlock’s Galaxy portrait as a sign of Dickens’s increasing awareness—and uneasiness—with the potential reproduction of one’s image, as well as a sign of the rising middle class. As Thomas puts it, “it is fitting that the plot of Bleak House should come to focus upon a pair of portraits—one a distinguished oil, the other a mass-produced copy—in recounting the scandalous fall of an old aristocratic family and the solution of a murder mystery” (Detective Fiction 133). Although daguerreotypes are one-of-a-kind photographic images, engraving and increasingly photographic technologies were making image reproduction more ubiquitous by the 1850s. In Bleak House, this reproduction is Lady Dedlock’s potential undoing, for through the circulation of her image, the likes of Guppy and Weevle may ponder her likeness at length. While Guppy may have recognized the similarity between Lady Dedlock and Esther when looking at the Chesney Wold portrait, the circulation of Lady Dedlock’s Galaxy portrait—a kind of celebrity portrait presaging the cartomania of the 1860s—opens this connection to anyone and everyone. Although the mass-produced image reveals a secret in Bleak House, it does not expose all of the novel’s mysteries—it does not explain who shot Tulkinghorn, for instance, or what happened to Krook. It does not resolve Jarndyce v. Jarndyce. It exposes but also misdirects, suggesting revelations that nevertheless do not resolve all of the novel’s major plot points.

Dickens was aware that his photographic celebrity image was in some respects a lie, and his discomfort is specifically with the multiplication of that lie. This may be read as symptomatic of his well-documented oscillation between private person and public persona—a professional writer who, as Grahame Smith notes, had a “general hostility toward public life” (“Life and Times” 12). Indeed, Dickens was not the only Victorian novelist dissatisfied with photography. George Eliot describes the photographs seen before meeting a person as “detestable introductions, only less disadvantageous than a description given by an ardent friend to one who is neither a friend nor ardent” (5:437). Like Dickens, Anthony Trollope admits, “I hate sitting for a photograph” (682). Yet photographic portraiture was part of Victorian celebrity authorship. Celebrity functions theatrically, as Sharon Marcus puts it, because “it combines proximity and distance and links celebrities to their devotees in structurally uneven ways” (1000). Writing about Victorian celebrity and photographic portraiture, Alexis Easley similarly argues that the discourse surrounding celebrity was “premised on what could be seen and known about popular authors” as well as “the mysterious and unknowable aspects of their lives and works” (12). Indeed, the tension between proximity and distance is spatial and temporal: “although celebrity culture was premised on reconstruction of the past, it was also focused on the ephemeral world of the day-to-day literary marketplace” (11). In the Victorian era, the literary marketplace was becoming more dominated by the visual. In a Victorian culture obses...