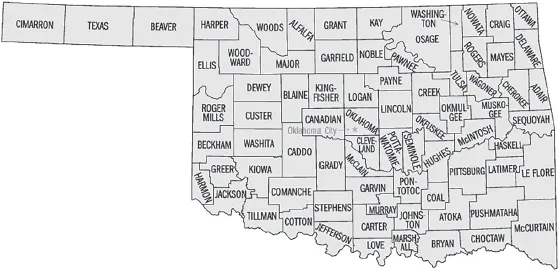

![]()

Chapter One: Wonders of the West

“While waiting for a Moses to lead us into the Promised Land, we have forgotten how to walk.”

—Wendell Johnson

From: United States Census 1900, https://familysearch.org/learn/wiki/en/United_States_Census_1900

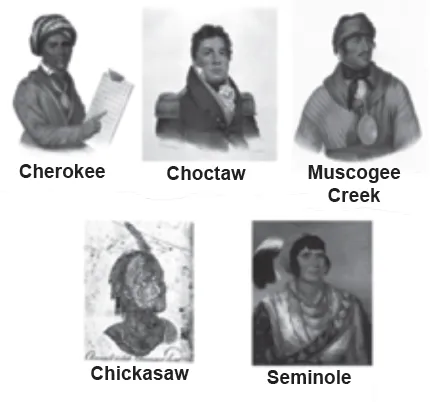

Oklahoma once ranked as a wonder of the West, a destination discovery romanticized in rhetoric resonant with black audiences. Persons of African ancestry first traversed modern-day Oklahoma with Spanish explorers in the 1500s. They later accompanied the Five Civilized Tribesxxiii (the Choctaw, Seminole, Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), and Chickasaw), forcibly resettled from the Southeastern United States in the 1830s and 1840s.xxiv Still later, propaganda propelled the great black migration that came as part of the post-Reconstruction black diaspora from the South in the 1880s and 1890s.xxv At each turn in the unfolding saga of this once-remote refuge, race remained relevant.

Oklahoma’s congenital struggles with race formed the backdrop for the Sawners’ remarkable lives. The Sawners were who they were because they were where they were.

On November 16, 1907, Oklahoma and Indian Territories merged into the present-day State of Oklahoma. Prior to that time, Oklahoma Territory, the western half of this land of the red people,xxvi captured the imaginations of restive Americans, both black and white.

Oklahoma Territoryxxvii first opened for general settlement on April 22, 1889. Like predators in the wild, Oklahoma Territory newcomers foraged for new beginnings and, more specifically, economic opportunities, in these “Unassigned Lands.”xxviii Corporate interests like the railroads saw Oklahoma Territory as fertile field for market expansion and revenue-generation and as a new profit center.xxix

With increasing frequency, African American migrants from the Deep South escaped the straightjacket of Southern political, economic, and social domination. Oklahoma Territory, once home to several Indian tribes,xxx ranked among the most desirable of destinations.xxxi The fascination with Oklahoma Territory was more than mere wanderlust. Widely perceived by non-Indians to be undiscovered, uninhabited, and unspoiled, this wonder of the West held virtually unlimited promise. For forlorn African Americans, tall tales about this faraway Eden grew to utopian proportions. Imaginations ran wild.

Imagine an all-black state in the land of the red people.

A place of possibility and promise:

Civil rights,

Economic opportunity,

Social equality—

Right here in Oklahoma.

A place with black leadership:

A governor,

An entrepreneur,

A booster—

Right here in Oklahoma.

A place of relative peace:

A safe place,

A just place,

A more perfect place—

Right here in Oklahoma.

Imagine.

Imagine.

Imagine.

Imagine an all-black state in the land of the red people.xxxii

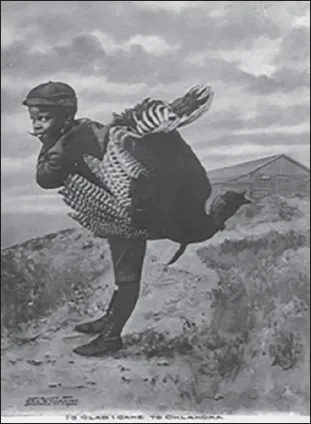

“I’s glad I came to Oklahoma”—postcard, circa 1907, touting the Oklahoma Promised Land.xxxiii

John Booker, African American pioneer and participant in the 1891 land run.xxxiv

The Booker brothers, sons of John and Mary Booker, 1918; left to right: Andersen Booker, Thomas Booker, Mercer Booker, Frank Booker, and John Booker.xxxv

A special July 1, 1907, census captured the demographic impact of the Oklahoma allure. On that date, the population of Oklahoma Territory stood at 733,062; that of Indian Territory, 681,115. Those numbers reflected a dramatic seven-year increase in population of 334,731 (84 percent) for Oklahoma Territory and 289,055 (78.9 percent) for Indian Territory. The population of Indian Territory more than doubled from 1890 to 1900; that of Oklahoma Territory in the same period more than quadrupled. Oklahoma Territory boasted the largest, and Indian Territory the second largest, population increase between 1890 and 1900 of any state or territory in the United States.xxxvii

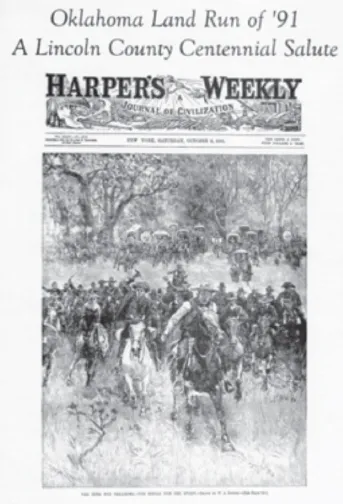

Reproduction of the October 3, 1891, Harper’s Weekly depicting the Land Run of 1891 through the eyes of artist W.A. Rogers.xxxvi

The demographic stew that fed Oklahoma’s rapid expansion often simmered and occasionally boiled over. African American aspirations clashed with entrenched notions of white supremacy in a land once reserved for the American originals.

Like just the right blend of salt and pepper added to this ingredient-rich mix, George and Lena Sawner lent a sense of balance, earning the trust and respect of all whom they met. The Sawners played a pivotal role in the business, education, and political spheres in nascent, racially-challenged, Oklahoma. They walked the racial tightrope that spanned the yawning chasm of difference and distrust between, primarily, black and white Oklahomans. Largely on their account, Chandler remained calm amidst the storms of racial tumult that battered Oklahoma and the nation. The Sawners’ lives and the unusual town that hosted them offer lessons for the ages.

Who were the Sawners’ contemporaries? What was the state of race relations in American during the Sawner era? How and why did race relations in Chandler differ from those in other Oklahoma communities? The answers to these questions lie, at least in part, in post-Civil War developments and migrations.

Swept up in the winds of social change after the collapse of Reconstruction, African Americans blew into the Oklahoma Territory with gale-force energy. This alien acreage beckoned like a sultry siren. And she would prove just as beguiling.

African Americans, dreamers who fantasized about an all-black state within the Oklahoma Territory, faced a rude awakening. Deferred and ultimately discarded, this longing for a cocooned, all-black existence grew out of a yearning for black self-actualization. African Americans simply wanted a place where they, too, could live out, unmolested, the promise of this “sweet land of liberty.”xxxviii Some saw it, or at least romanticized about it, in the lands of the untested Oklahoma Territory.

Even as this ultimate reverie faded, another vision, almost as intriguing and even more enduring, took shape. This latter dream morphed into reality. A number of new, all-black towns and settlements sprang up all across Oklahoma Territory and Indian Territory.

The founding of these all-black towns and the imaginings of an all-black state helped lay the foundation for African American progress during the twentieth century.xxxiv The epic tale of Oklahoma’s all-black town movement is a quintessentially American narrative.

Gallery of the Five Civilized Tribes; portraits drawn/painted between 1775 and 1850.xl

Five Civilized Tribes Museum in Muskogee, Oklahoma.xli

Picture it: An all-black state founded by nineteenth century “Negroes” pining for social, political, and economic rights denied them in a schizophrenic America. The Constitutional idealism embodied in words like “freedom,” “justice,” and “equality” simply did not square with the realities on the ground. Escape to an all-black state seemed a palatable—even desirable—solution. As envisioned, an all-black state would be a gap-filler between American aspirations and African American actuality.

The prospect of an all-black state captured the attention of the nation. In 1890, amidst a groundswell of support among African Americans, United States President Benjamin Harrison took note of ascending ambitions among African Americans in Oklahoma Territory.

While efforts to establish an all-black state in Oklahoma Territory fell short, all-black towns like Boley, Clearview, Langston, Red Bird, Rentiesville, and Taft emerged on both sides of the territorial dividing line. So, too, did centers of music, culture, and commerce in segregated urban communities like “Deep Deuce” in Oklahom...