Article 27

1. States Parties recognize the right of every child to a standard of living adequate for the child’s physical, mental, spiritual, moral and social development.

2. The parent(s) or others responsible for the child have the primary responsibility to secure, within their abilities and financial capacities, the conditions of living necessary for the child’s development.

3. States Parties, in accordance with national conditions and within their means, shall take appropriate measures to assist parents and others responsible for the child to implement this right and shall in case of need provide material assistance and support programmes, particularly with regard to nutrition, clothing and housing.

4.1 Introduction

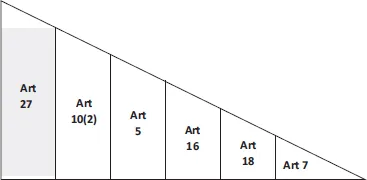

Article 27 is the first CRC article identified in the normative and conceptual framework outlined in Part A. Its immediate relevance to TLM is twofold. First, it protects children’s right to a standard of living that is adequate not only for their physical development, but also for their mental, spiritual, moral and social development.1 (For the purposes of brevity, these non-physical aspects will be referred to hereafter as a child’s psychosocial development.) Second, it entitles parents to appropriate measures of assistance from States to meet their primary responsibility to secure the necessary living conditions to fulfil this right of children.2 This chapter examines these separate but connected prongs of Art 27 in light of both labour-sending and labour-receiving States encouraging parental migration as a measure to enable parents to provide for their children’s development needs.

The chapter argues that the promotion of parental migration for employment by States has two consequences. The first is that it inappropriately shifts the entire burden of providing for children’s material needs to parents who have limited alternatives to migration in the face of poverty and un- or under-employment. This is despite the duty of labour-sending States to assist parents in need (subject to available national means) to provide for children’s basic material requirements.3 The second is that TLM completely ignores the potential impact of prolonged parental absence on children’s psychosocial development and well-being. This is despite labour-sending States having the duty to assist parents to secure the living conditions necessary for their children’s psychosocial development needs as well as their material needs; and labour-receiving States having a duty to not cause harm to children outside their jurisdiction in line with the principle of international cooperation.4 These arguments comprise the first two parts of this chapter. Together, they demonstrate that it is misleading to conceive of TLM in its current forms as an ‘appropriate’ measure of assistance to parents by States in fulfilment of their obligations under Art 27(3). The notion of ‘appropriate’ assistance is defined in Section 4.2.1.

On the contrary, while TLM may create an opportunity for parents to provide for their children economically, this chapter demonstrates that the provision of parental assistance is by no means an intended purpose of TLM. Rather, is shows that findings as to whether TLM improves children’s education, health and material outcomes are mixed and there are considerable concerns about the impact of TLM on children’s psychosocial development and well-being. The latter is largely attributed to the disruption that TLM causes to the child-parent relationship. It highlights the heightened risks to children when their relationship with their primary caregiver is disrupted at the time of migration, which is increasingly so with the feminisation of migration for care and domestic work.5 The chapter argues that such disruption to the child-parent relationship, which is protected in the CRC, reflects the inappropriateness of TLM as a measure of assistance to parents to provide for their children.

The final part of this chapter considers the significance of a child’s age and capacity in relation to understanding their development needs and how they may be impacted by parental migration. It argues that appropriate measures of assistance to parents cannot be determined without due consideration of the age of their children at the time of separation. It emphasises that if TLM is to genuinely assist parents to provide for their children’s development needs, then it must incorporate measures that actively support children and parents to sustain their relationship in the event of migration. To be effective, these measures must be age-appropriate and respond to children’s changing development needs. Moreover, their implementation must be supported by both labour-sending and labour-receiving countries. This is because children’s capacity to enjoy and benefit from their relationship with their parents in the context of TLM is determined by transnational arrangements between States.

1 CRC art 27(1).

2 CRC art 27(3).

3 CRC art 27(3).

4 The principle of international cooperation is discussed in Chapter 3 (see Section 3.3).

5 The feminisation of migration is discussed in Section 4.3.2(i) below.