1

REFLECTIVE ANALYSIS OF THE FAIRY TALE “THE LOVE OF THREE ORANGES”

by Carlo Gozzi

Translated, introduced, and annotated by Maria De Simone

The Love of Three Oranges: A Multilayered Manifesto

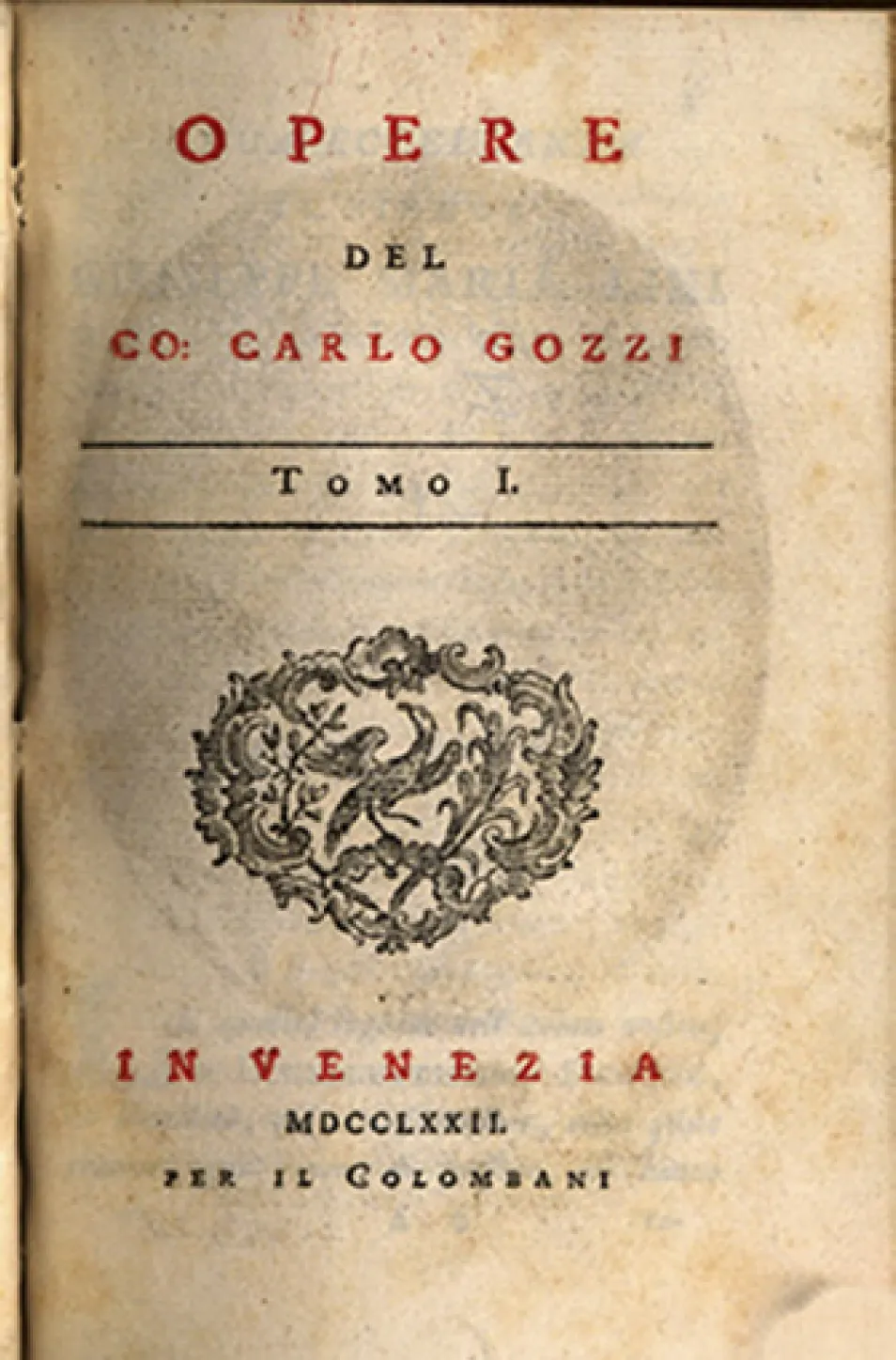

Carlo Gozzi’s theatrical fairy tales, or fiabe, have been translated and adapted into many different languages and national contexts since Venetian editor Paolo Colombani first published them between 1772 and 1774 (fig. 1.1).1 Their appealing combination of familiar fairy-tale plots, commedia dell’arte characters, and opportunities for spectacular production effects firmly grounded their long-term success in Italy and beyond. The Love of Three Oranges, chronologically the first of Gozzi’s ten fiabe, differs substantially from the other nine in the Colombani edition because of its unconventional style. Gozzi’s later fiabe are play scripts in dialogue. In contrast, the Reflective Analysis of the Fairy Tale “The Love of Three Oranges” (Analisi riflessiva della fiaba L’amore delle tre melarance) appears in a memoir format that passes on Gozzi’s recollections of the production as performed by Antonio Sacchi and his company on opening night, January 25, 1761, at the San Samuele Theatre in Venice. Besides reproducing a plot summary with a few scripted sections in Martellian verse, the published version includes Gozzi’s “reflections” on the production’s satirical goals, mise-en-scène, and reception. Gozzi never articulated a full justification of this stylistic choice: perhaps he never kept a copy of the script, or perhaps the play initially existed only as a plot outline.2 In any case, his memoir format is a compelling component of the work’s successful formula—namely, a corpus of references and self-references that explain the production’s staging choices and illuminate the cultural, historical, and polemical context of Three Oranges for later readers.

Figure 1.1. Title page from Opere del Co: Carlo Gozzi. Vol. 1 (Venice: Il Colombani, 1772). 852.1G7491 I, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York. Courtesy of HathiTrust, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nnc1.0038978024.

Gozzi’s metatheatrical glosses fall into three categories.3 First, he includes the inspirations for his allegorical parody: “bourgeois” comedies of character by Carlo Goldoni and pompous tragedies by Pietro Chiari, both his contemporaries and playwrights for competing Venetian theatres. Second, he explains his choice of subject matter and style. Third, he notes audience responses, especially moments that, according to Gozzi, received the most enthusiastic applause. This self-referential frame comprises roughly half of Gozzi’s Reflective Analysis, yet most English translations have cut it, and no modern English adaptations of the fiaba have ever featured it onstage.4

This short introduction underscores both aspects of Gozzi’s first fiaba—its fantastical content and its self-referential frame. As in many fairy tales, Gozzi’s fantastical characters and plot turns entertain those who take pleasure in recognizing their provenance, allegorical meanings, and morals. The self-referential frame in the Reflective Analysis, on the other hand, explicitly directs the readers’ interpretation of both the text and the performance event that the text reconstructs.

The fiaba’s story about an orange-pursuing hypochondriac prince is a mélange of fairy-tale characters and events drawn from eighteenth-century Italian folklore, Venetian culture, and various literary sources. In his review of the premiere in the Gazzetta Veneta (Venetian gazette), Gozzi’s brother Gasparo attributed the play’s source to Giambattista Basile’s Neapolitan “The Three Citrons” (Le tre cetra)—the last tale in The Tale of Tales (Lo cunto de li cunte, 1636), a series of fifty fairy tales framed by the story of a melancholic princess.5 In this framing tale, the princess’s melancholia is cured after laughing at an old woman who slips and falls. The old woman condemns the princess to marry a sleeping prince whom she can awaken only by filling a pitcher with her tears. A Moorish slave steals the filled pitcher and claims the prince in her stead. The new queen demands that her husband entertain her with stories. When the prince hires ten storytellers who each tell five stories over five days, the melancholic princess is among them. The true princess narrates “The Three Citrons,” an allegory aimed at uncovering the imposter. In this tale, a prince seeks a bride of a very particular complexion—the same shade of pink that a drop of his blood produces when mixed with ricotta cheese. Three women give him three citrons—large, sweet lemons—that conceal thirsty maidens; two do not survive, and the third becomes the prince’s bride. A Moorish slave transforms the princess into a dove and takes her place. The imposter’s treachery is disclosed once the dove’s feathers sprout a citron tree with fruit that contains the “reborn” princess.

Recent scholars, including Beniscelli and Baldyga in this volume, are wary of restricting Gozzi’s fantastical inspirations to the single text mentioned in Gasparo’s review, noting that Gozzi’s fiaba shares greater similarities with some northern Italian oral versions of the Oranges tale.6 Basile’s stories themselves were drawn from folklore, which further complicates questions of origin and authorship. Three Oranges and The Tale of Tales do, however, share several of what became Gozzi’s most whimsical plot points and characters: a melancholic prince, a magical old woman who slips and falls, healing laughter, a cursed quest for three fruits that conceal three maidens, and the princess’s transformation into a dove. Gozzi derives additional elements from thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Italian literary sources. For example, Gozzi’s devil, whose bellows send the prince, Tartaglia, and the royal jester, Truffaldino, forward in their journey, recalls Luigi Pulci’s similarly propelling devil in the satirical epic poem Morgante (1478) (fig. 1.2).7 Similarly, Farfarello, the devil who apprises Wizard Celio, Tartaglia’s protector, of the witch Fata Morgana’s evil dealings, echoes Dante Alighieri’s The Divine Comedy (ca. 1304–21).8

These varied references provided an opportunity for all social strata watching Three Oranges to experience the pleasure involved in recognizing sources. Although Morgante and The Divine Comedy were inaccessible to those without relevant education, lower classes were familiar with oral versions of the Three Oranges folk tale told by public storytellers.9 Furthermore, audience members who were frequent theatregoers recognized allegorical references to works by Goldoni and Chiari. For example, spectators familiar with Pietro Chiari’s play Ezelino, Tyrant of Padua (Ezzelino, il tiranno di Padova, ca. 1760) could compare Gozzi’s bellows-wielding devil not only with Pulci but also with the exceptionally fast horse Chiari used to speed the journey of one of his characters.10 As Ted Emery’s essay in this volume argues, the staged version of Three Oranges took into account two kinds of spectators: “a ‘naïve’ viewer who is unaware of the author’s polemic with Goldoni and Chiari but has excellent knowledge of the play’s source” and one who is “able to decode the play’s allegory.”11 Gozzi captured both interpretative frameworks in his Reflective Analysis, but he makes the latter explicit through the self-referential clarifications that he interjects into his recollections of the premiere.

Cultural references to contemporary Venice also entertained a variety of spectators. In the fiaba, Gozzi’s villains scheme to serve Tartaglia “panatella,” a dish made from broth and grated bread that was popular with dyspeptic Venetians. They planned to lace it with paper charms (brevi) written in Martellian verse, however, so the soup would upset rather than calm the Prince’s stomach. Like Chiari’s and Goldoni’s plays, which, as Gozzi described, “were written in Martellian verse and bored the audience to death with the monotony of the rhyme,” these paper charms would “slowly kill [Tartaglia] with their hypochondriacal effects.”12 Similarly, the King of Cups and the Knight of Cups—Tartaglia’s father and enemy Leandro, respectively—recall Venice’s eighteenth-century gambling culture, as they are costumed as playing cards. Some audience members may also have decoded a reference to Maria Boiardo’s fifteenth-century epic poem Orlando in Love (Orlando innamor...