![]()

1

Food System Concentration: A Political Economy Perspective

Power is not a means, it’s an end.

—O’BRIEN (NINETEEN EIGHTY-FOUR)

If you go into a typical grocery store in the United States and make your way to the margarine case, you will probably see approximately a dozen different brands. If you look very closely at the packaging, however, you may find a small seal, which signifies the majority of these are owned by either Upfield or ConAgra (Table 1.1). Although these two firms dominate the margarine market—they combine for approximately two-thirds of US sales, and Upfield controls 27 percent of sales globally (Grocery Headquarters 2013; Adbrands 2018)—their power is hidden from us through an illusion of numerous competing brands. Margarine is not a unique case, and while the number of options offered may differ, similar patterns can be found in almost every food or beverage category. The bread shelves, for example, may provide slightly more choices, but this conceals the fact that Grupo Bimbo and Flowers Foods each own more than two-dozen leading brands, and together control approximately half of the US market (Howard 2016). The wine aisle may contain literally hundreds of brands, but it is very difficult to discern that scores of these, as well as more than half of US sales, are controlled by only three companies: Gallo, The Wine Group, and Constellation (Howard et al. 2012). In nearly every other stage of the food system, including retailing, distribution, farming, and farm inputs (e.g., seeds, fertilizers, pesticides), a limited number of firms or operations tend to make up the vast majority of sales.

TABLE 1.1 Ownership of margarine brands

| Upfield | ConAgra |

| Becel | Blue Bonnet |

| Brummel & Brown | Fleischmann’s |

| I Can’t Believe It’s Not Butter | Move Over Butter |

| Imperial | Parkay |

| Promise | Smart Balance/Earth Balance |

| Shedd’s Spread Country Crock | |

Is this a problem? An increasing number of people argue that indeed it is: the firms that dominate these industries are criticized for a long list of purported negative impacts on society and the environment. Just a few examples include:

• Walmart, which controls approximately one quarter of US grocery retailing, is challenged for exploiting its suppliers, taking advantage of taxpayer subsidies, and paying extremely low worker wages.

• McDonald’s, which controls 17 percent of US fast food sales, is also critiqued for extremely low wages, as well as the negative health consequences and environmental impacts of its products.

• Tyson, which controls 20 percent of US chicken, pork, and beef processing is reproached for its pollution, poor treatment of farmers, and contributions to the decline of rural communities.

• Monsanto, which controlled over 26 percent of the global commercial seed market before its acquisition by Bayer, was denounced for its influence on government policies, spying on farmers it suspected of saving and replanting seeds, and the environmental impacts of herbicides tied these seeds.

These impacts tend to disproportionately affect the disadvantaged—such as women, young children, recent immigrants, members of minority ethnic groups, and those of lower socioeconomic status—and as a result, reinforce existing inequalities (Allen and Wilson 2008). Like ownership relations, the full extent of these consequences may be hidden from the public view.

This book seeks to illuminate which firms have become the most dominant, and more importantly, how they shape and reshape society in their efforts to increase their control. These dynamics have received insufficient attention from academics, and even critics of the current food system. The power of dominant firms extends far beyond narrow economic boundaries, for example, providing them with the ability to damage numerous communities and ecosystems in their pursuit of higher than average profits. The social resistance provoked by these negative consequences is another area that is less visible to the majority of the population. When such resistance is evident at all, it frequently appears insignificant, failing to challenge the direction of current trends. Even very small movements, however, may influence which firms end up winners or losers, or close off particular avenues for growth. These accomplishments also suggest potential limits, and therefore the possibility that dominant firms may experience much greater threats to their power in the future.

Increasing Concentration

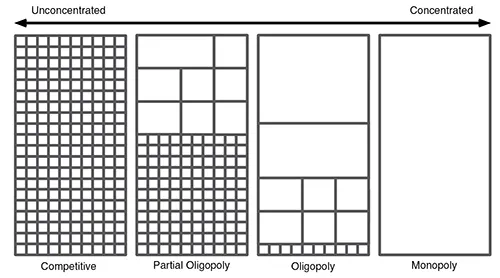

Concentration is a term used to describe the composition of a given market, and especially its potential impacts on competition. At one end of the spectrum are markets that are described as unconcentrated or fragmented, which economists consider to be freely competitive (Figure 1.1). In this type of market, sellers are “price takers,” and lack the ability to raise prices. At the other end of the spectrum are concentrated markets, which in their most extreme form are monopolies controlled by just one firm. In these situations there are no alternatives, and the monopolists have substantial power to raise prices without losing customers. Also at this end of the spectrum are oligopolies, in which markets are dominated by several large firms, but are characterized by very limited forms of competition; these are sometimes described by critics as “shared monopolies” (Bowles, Edwards, and Roosevelt 2005, 265). In the middle are partial oligopolies, in which large firms may have some control over their prices, but lack the power to significantly reduce competition, as is the case with oligopolies. The word monopoly is derived from the Greek words for single (mono) and seller (polein), but concentrated markets may also occur among buyers, as found in a monopsony or oligopsony (derived from the Greek word for buy, opsōnía).

FIGURE 1.1 Levels of market concentration.

Each rectangle represents a single, hypothetical firm, with size proportional to market share.

There has been a strong tendency in more industrialized countries, including the United States, to move away from competitive markets, and toward higher levels of concentration (Heffernan, Hendrickson, and Gronski 1999; Du Boff and Herman 2001). As markets go through this process of consolidation, the average firm size increases, barriers to entry for other firms rise, and the remaining firms have more influence over prices, as well as a greater potential for higher profits. These are some of the widely recognized reasons why markets tend to become less competitive—firms understand the benefits to be gained by expanding their market share, reducing the number of competing firms, and increasing their leverage over the terms of exchange (Foster and McChesney 2012). These trends are most evident in industries such as airlines and telecommunications, in which the US government intervened to encourage greater competition, only for them to eventually return to more oligopolistic structures (Brock 2011).

Potential Negative Impacts

Governments sometimes intervene when industries reach a high level of concentration because such limited competition may lead to numerous negative outcomes. Market consequences could include consumers paying higher prices, suppliers receiving lower prices, or reduced innovation. Oligopolistic firms have disincentives to reduce profits by investing in research and development, particularly when doing so could lead to lower barriers to entry, and increasing competition. In addition, large organizational size can discourage innovation indirectly, via complex bureaucracies that are reluctant to approve new ideas (Brock 2011). Increasing size can be an advantage for reducing prices paid for inputs, however, as smaller suppliers may have fewer alternative buyers for their products, and less organizational capacity to negotiate the best possible terms (Calvin et al. 2001).

In order to raise consumer prices, it is not necessary for executives to gather in one room and conspire to achieve these markups. When just a few firms control a large share of the market they can simply indicate their intention to raise prices, and the others will benefit by following suit, a strategy that is called price signaling (Baran and Sweezy 1966). Oligopolistic firms can more easily pressure each other to avoid price wars that would lower their profits. The result is an unwritten rule that rivalries based on advertising, product differentiation, and reducing labor costs are expected, but competing on price is unacceptable. John Bell, a former CEO of a coffee company that was eventually acquired by Kraft, explained that he was constantly reinforcing this message to rivals through his speeches and media interviews in order to prevent “the natural competitive reaction.” Lowering prices was given the code word “non-strategic” in public communications, and emphasizing his opposition to it was “an indirect means of telling competition to ‘play ball’” (Bell 2012).

Nevertheless, executives in industries controlled by a small number of firms may go beyond signaling, and are occasionally even caught conspiring to fix prices. A few examples include:

• The US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) discovered in the mid-1960s that leading bakeries and retailers in Washington State had met frequently, and agreed to increase the price of bread by 15 to 20 percent (Parker 1976).

• In 2013, Hershey pleaded guilty to working with other large chocolate manufacturers (Mars, Nestlé, and Cadbury) to raise prices in Canada. While the other firms denied the charges, together they paid more than $22 million to settle a resulting class-action lawsuit (Culliney 2013).

• Western European governments have reported numerous schemes to raise food prices in recent years (e.g., beer, flour, bananas, chocolate, and dairy products), which have resulted in fines totaling hundreds of millions of dollars.

• Th...