![]()

Gardening & Melancholy

It is crucial to note the subtitle of 18th-century Europe’s most famous novel, written in three inspired days in 1759: Candide, or Optimism. If there was one central target that its author wanted satirically to destroy, it was the hope of his age, a hope that centred around science, love, technical progress and reason. Voltaire was enraged. Of course science wasn’t going to improve the world; it would merely give new power to tyrants. Of course philosophy would not be able to explain away the problem of evil; it would only show up our vanity. Of course love was an illusion, power a chimera, humans irredeemably wicked and the future absurd. Of all this, his readers were to be left in no doubt. Hope was a disease and it was Voltaire’s generous goal to try to cure us of it.

Nevertheless, Voltaire’s novel is not simply a tragic tale, nor is his own philosophy mordantly nihilistic. The book ends on a memorably tender and stoic note; the tone is elegiac; we encounter one of the finest expressions of the melancholic viewpoint ever written. Candide and his companions have travelled the world and suffered immensely: they have known persecution, shipwrecks, rapes, earthquakes, smallpox, starvation and torture. They have – more or less – survived and, in the final pages, find themselves in Turkey (a country Voltaire especially admired), living on a small farm in a suburb of Istanbul. One day they learn of trouble at the Ottoman court: two viziers and the mufti have been strangled and several of their associates impaled. The news causes upset and fear in many. Near their farm, Candide, walking with his friends Martin and Pangloss, passes an old man who is peacefully and indifferently sitting under an orange bower next to his house:

Pangloss, who was as inquisitive as he was argumentative, asked the old man what the name of the strangled Mufti was. ‘I don’t know,’ answered the worthy man, ‘and I have never known the name of any Mufti, nor of any Vizier. I have no idea what you’re talking about; my general view is that people who meddle with politics usually meet a miserable end, and indeed they deserve to. I never bother with what is going on in Constantinople; I only worry about sending the fruits of the garden which I cultivate off to be sold there.’ Having said these words, he invited the strangers into his house; his two sons and two daughters presented them with several sorts of sherbet, which they had made themselves, with kaimak enriched with the candied-peel of citrons, with oranges, lemons, pine-apples, pistachio-nuts, and Mocha coffee … after which the two daughters of the honest Muslim perfumed the strangers’ beards. ‘You must have a vast and magnificent estate,’ said Candide to the Turk. ‘I have only twenty acres,’ replied the old man; ‘I and my children cultivate them; and our labour preserves us from three great evils: weariness, vice, and want.’ Candide, on his way home, reflected deeply on what the old man had said. ‘This honest Turk,’ he said to Pangloss and Martin, ‘seems to be in a far better place than kings … I also know,’ said Candide, ‘that we must cultivate our garden.’

Voltaire, who liked to stir the prejudices of his largely Christian readers, especially enjoyed giving the idea for the most important line in his book – and arguably the most important adage in modern thought – to a Muslim, the true philosopher of the book known only as ‘the Turk’: Il faut cultiver notre jardin. ‘We must cultivate our garden’, or, as it has variously been translated, ‘we must grow our vegetables’, ‘we must tend to our lands’ or ‘we need to work our fields’.

What did Voltaire mean by his gardening advice? That we must keep a good distance between ourselves and the world, because taking too close an interest in politics or public opinion is a fast route to aggravation and danger. We should know well enough at this point that humans are troublesome and will never achieve – at a state level – anything like the degree of logic and goodness we would wish for. We should never tie our personal moods to the condition of a whole nation or people in general, or we would need to weep continuously. We need to live in our own small plots, not the heads of strangers. At the same time, because our minds are haunted and prey to anxiety and despair, we need to keep ourselves busy. We need a project. It shouldn’t be too large or dependent on many other people. The project should send us to sleep every night weary but satisfied. It could be bringing up a child, writing a book, looking after a house, running a small shop or managing a little business. Or, of course, tending to a few acres. Note Voltaire’s geographical modesty. We should give up on trying to cultivate the whole of humanity; we should give up on things at a national or international scale. Take just a few acres and make those your focus. Take a small orchard and grow lemons and apricots. Take some beds and grow asparagus and carrots. Stop worrying yourself with humanity if you ever want peace of mind again. Who cares what’s happening in Constantinople or what’s up with the grand mufti? Live quietly like the old Turk, enjoying the sunshine in the orange bower next to your house. This is Voltaire’s stirring, ever-relevant form of horticultural quietism. We have been warned – and guided.

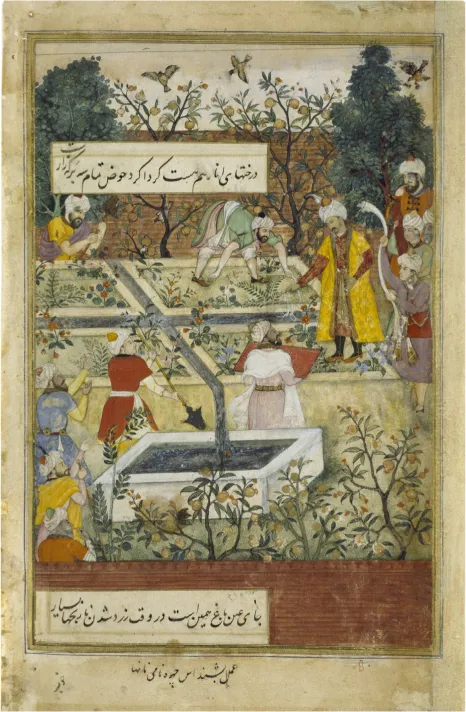

It is no coincidence that Voltaire put his lines about the cultivation of the garden into the mouth of a Muslim. He had done a lot of reading about Islam for his Essay on Universal History, published three years before, and properly understood the role of gardens in its theology. For Muslims, because the world at large can never be rendered perfect, it is the task of the pious to try to give a foretaste of what should ideally be by creating a well-tended garden (and where that is not possible, a depiction of a garden in a rug). There should be four canals that allude to the four rivers of paradise in which are said to flow water, milk, wine and honey, and where they intersect represents the umbilicus mundi, the navel of the world, where the gift of life emerged. Gardening is no trivial pastime. It’s a central way of shielding ourselves from the influence of the chaotic, dangerous world beyond, while focusing our energies on something that can reflect the goodness and grace we long for.

Melancholics know that humans – ourselves foremost among them – are beyond redemption. We melancholics have given up on dreams of complete purity and unblemished happiness. We know that this world is, for the most part, hellish and heartbreakingly vicious. We know that our minds are full of demons that will not leave us alone for long. Nevertheless, we are committed to not slipping into despondency. We remain deeply interested in kindness, in friendship, in art, in family life – and in spending some very quiet local afternoons gardening. The melancholic position is ultimately the only sensible one for a broken human. It’s where one gets to after one has been hopeful, after one has tried love, after one has been tempted by fame, after one has despaired, after one has gone mad, after one has considered ending it – and after one has decided conclusively to keep going. It captures the best possible attitude to pain, and the wisest orientation of a weary mind towards what remains hopeful and good.

Bishndas, illustration from the Baburnama showing the Mughal emperor Babur supervising the laying out of a Kabul garden, c. 1590

![]()

Image credits

p. 10t Nicholas Hilliard, Young Man Among Roses, c. 1585–1595. Vellum and watercolour, 13 cm × 3 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, England / Wikimedia Commons

p. 10b Isaac Oliver, Edward Herbert, 1st Baron Herbert of Cherbury, 1613–1614. Watercolour on vellum, 18.1 cm × 22.9 cm. Powis Castle, Welshpool, Wales. National Trust / Wikimedia Commons

p. 13 Albrecht Dürer, Melencolia I, 1514. Engraving, 24.5 cm × 19.2 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., USA. Gift of R. Horace Gallatin. Image courtesy National Gallery of Art.

p. 17 Zacharias Dolendo, Saturn as Melancholy, 1595.Rijksmuseum.

p. 36t Workshop of Giovanni Bellini, Madonna and Child, c. 1510. Oil on wood, 34.3 cm × 27.6 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA. The Jules Bache Collection, 1949. Image courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

p. 36b Sandro Botticelli, Madonna and Child, c. 1470. Tempera on panel, 74 cm × 54 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., USA. Andrew W. Mellon Collection. Image courtesy National Gallery of Art.

p. 40 NASA / JHUAPL / SWRI

p. 91 Rainer Ebert / Wikimedia Commons

p. 92 Paul Kozlowski + © F.L.C. / ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2021

p. 93 Luis García / Wikimedia Commons

p. 112 Agnes Martin, Morning, 1965. Acrylic paint and graphite on canvas. 182.6 cm × 181.9 cm. Tate Museum, London, England. © Photo: Tate © Agnes Martin Foundation, New York / DACS 2021

p. 115 Agnes Martin Gallery, Harwood Museum of Art, Taos, NM. © Agnes Martin Foundation, New York / DACS 2021. Photo: Courtesy Rick Romancito / The Taos News

p. 117 Agnes Martin, I love the Whole World, 1993. Acrylic paint and graphite on canvas, 152.4 cm × 152.4 cm. Private Collectio...