eBook - ePub

Design Thinking for Every Classroom

A Practical Guide for Educators

Shelley Goldman, Molly B. Zielezinski

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 156 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Design Thinking for Every Classroom

A Practical Guide for Educators

Shelley Goldman, Molly B. Zielezinski

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Designed to apply across grade levels, Design Thinking for Every Classroom is the definitive teacher's guide to learning about and working with design thinking. Addressing the common hurdles and pain points, this guide illustrates how to bring collaborative, equitable, and empathetic practices into your teaching. Learn about the innovative processes and mindsets of design thinking, how it differs from what you already do in your classroom, and steps for integrating design thinking into your own curriculum. Featuring vignettes from design thinking classrooms alongside sample lessons, assessments and starter activities, this practical resource is essential reading as you introduce design thinking into your classroom, program, or community.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Design Thinking for Every Classroom als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Design Thinking for Every Classroom von Shelley Goldman, Molly B. Zielezinski im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Éducation & Enseignement des sciences et technologies. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

PART I

The Four Stages of the Design Thinking Process

1

Exploring the Problem Space

DOI: 10.4324/9780429273421-2

Figure 1.1

(Credit: Saya Iwasaki)

In 2013, Shelley and I stood before a group of 40 students, teachers, parents, and school leaders just outside of Salt Lake City, Utah. We were leading a design thinking professional development (PD) to support this diverse group of stakeholders in jump starting the process of bringing design thinking to life at their school. Other than the principal, who had invited us, this group had no background in design thinking.

We created mixed design teams of five individuals, making sure each team included at least one teacher, student, parent, and school leader. This workshop would engage our learners through participation in a start-to-finish design challenge with their teams.

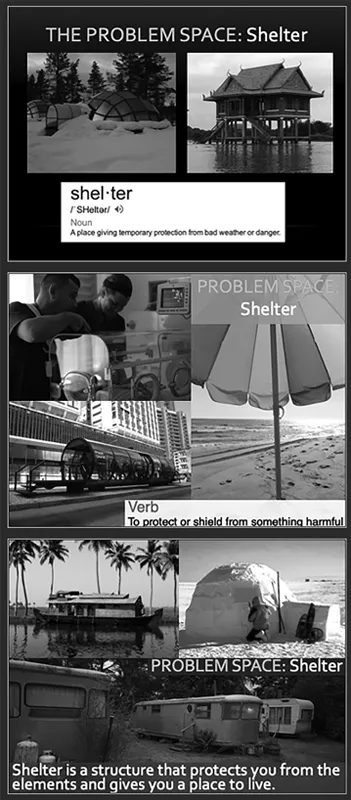

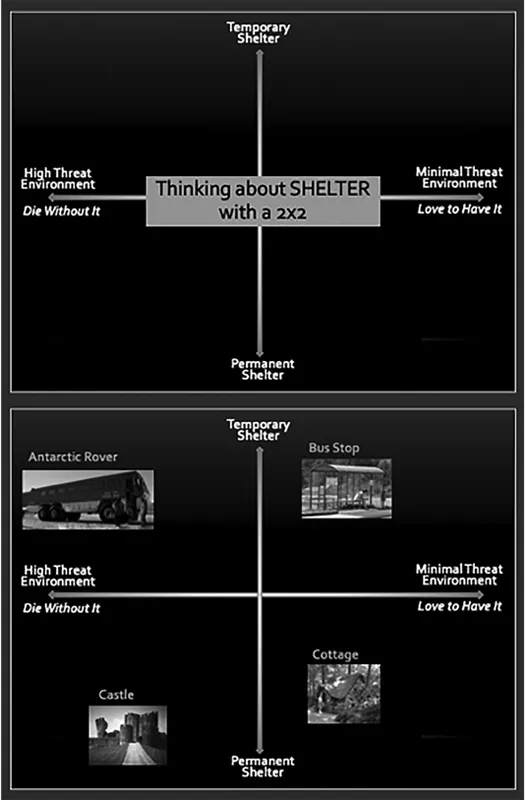

We started with some team building activities and then hit the ground running by introducing the problem space . A problem space is the broad area of focus in a design challenge. In this workshop, the problem space was shelter. We advanced rapidly through a slide deck that walked teams through definitions, purposes, and unique examples of shelters (see Figure 1.2 for excerpt from Shelter Slide Deck). We presented the teams with shelter-related questions that were meant to spark their interest. For example, we showed them pictures of igloos, caves, and houseboats. Then we engaged the team members in a think-pair-share activity in order to place some examples of shelters on a 2 × 2 matrix, deciding the extent to which shelters were either temporary or permanent and necessary or desired (see Figure 1.3 for visualization of this 2 × 2 matrix).

Figure 1.2 Background building excerpt from Shelter Challenge Slide Deck

(By: Molly B. Zielezinski)

Figure 1.3 Background building exercise featuring 2 × 2 matrix

(Credit: Molly B. Zielezinski)

We immersed the teams in the problem space before we posed the specific details about the upcoming design challenge. The idea was to hook them with varied visual examples, engaged discussion, and by tapping into their prior knowledge. This initial process was the first step in building background. Building background is the first phase of the design thinking process in K-12 classrooms. In the rest of this chapter, you will learn more about why it is important to build background, how to do this work as a teacher, and specifically how the standards for learning can be inspirational and utilized as you engage in design thinking with your students.

What Is Background Building?

We always start classroom design thinking challenges with background building. We believe it is essential for K-12 learners. We both are “learning researchers”, and the work in the field tells us that preexisting knowledge is variably present and can be fashioned quite successfully into new learnings. Students come into the classroom with preexisting knowledge, experiences, skills, and beliefs about the world and how it works. They may have particular ways in which they interpret information or events depending on their prior knowledge. When we take time to build on prior knowledge or establish a baseline of working knowledge, we will be doing the students a service by helping to set the stage for deeper understanding, complex thinking, or even innovative problem-solving. When we begin a design thinking challenge, we cannot assume that students have the necessary background knowledge on a problem space topic, so it's best if we give them the opportunity to establish some basics. In design thinking, we often talk about working in collaborative groups where students can bring various skills and prior experiences. We are also keenly aware that in classrooms, we need to open opportunities for all the students to achieve goals and meet and go beyond standards. In our shelter design thinking challenge, we built background knowledge for the students even though we knew they were working with teachers in small groups. This was meant for all—the students got to define what shelters were and understand some of their requirements and features, and the teachers on the teams had their knowledge refreshed and were able to be reminded that there are as many types of shelters as there are people and situations.

Establishing background knowledge in the design thinking problem space particular to the challenge also provides students with opportunities to experience research and develop important research and communication skills. If background research is done as an expectation at the start of design thinking challenges, students will surely develop the skills to delve in and find new and interesting ways to do the research and share their results. As you will see later in this chapter, there are unlimited ways to build background knowledge with students, depending on their age and skills. In the early grades it might mean looking through picture books or hearing a story being read; in the later grades it might involve independent research with reports to the larger classroom or interviews with experts in the field.

Building background knowledge can also be an opportunity to make connections among the subjects and content areas. It is a perfect opportunity for reading and literacy work in the content areas. We have built background by bringing the students in contact with literature, social studies, science, and math. In the shelter focused challenges, we have integrated engineering information about the features of shelters, such as which shapes are efficient in certain circumstances, and why triangles are important for strength. We've done experiments about climate and insulation, and read about shelters in different cultures and for different populations.

Like other stepping stones in the design thinking process, research and activities for background building can take place at the beginning of a challenge and also be woven through the projects. One of our favorite models is to start off, then intersperse background building activities as the challenge is developing.

In a design thinking project, it is necessary to build background so that designers can learn about the places where the design space is already saturated and places where there are unsolved issues, problems, or opportunities. Because design thinking strives to bring innovative, new solutions into the world, becoming informed about what already exists is helpful. It makes much more sense to innovate once you know where the thinking or concepts involved in any problem space currently stand. This is true whether you are a newbie or an experienced design thinker.

How to Build Background

As we have discussed, the first stage of the design thinking process is building background. Having all the students building background on the topics related to the challenge is an essential goal. As your students encounter problems in the classroom and problems in the world, they will be tempted to jump right into solutions. We find that adults are like this too. It seems like we are hardwired to confront new problems head on. Sometimes we do jump in and act on the spot, and that can be a healthy and invigorating response. Other times, we need to take time to understand the complexity or history involved in a problem that we are trying to solve. We also want to see the problem space from many angles and vantage points. That is not to say that we should not act in energetic ways in the problem-solving process. In design thinking, we sometimes call on instinctual or quick responses to understand this such as when we are creating energy through improv or creating solutions through brainstorming. Yet in this stage, we begin to develop deep and varied understandings of a topic. In design thinking, we try to gather background context before we begin to resolve problems and continue learning throughout the process. Before digging into solutions, experienced designers linger in the ambiguity of the context.

Here is an example of building background from Molly's classroom when she worked with middle school students in an underserved California community. Molly was working on her very first design challenge (that had been developed by a team Shelley worked with through an NSF middle school math curriculum project and then revised by the REDlab team). The problem space in this challenge was to design a shelter in Antarctica for scientists to do their work over winter. We know that there is a lot of information about the conditions in Antarctica and several shelters for scientists, such as the McMurdo Station that has been operating since 1955. Still, the Antarctic environment is always changing and new kinds of science being done are also placing demands on the shelter design and its impacts on the environment.

For middle school students, building background means setting the stage and becoming acquainted with the problem space. In the case of Antarctica, it means to do it as an explorer who is charting a new territory. Antarctica turns out to be a wonderfully rich topic for middle school students. It is a distant, yet compelling environment. So, when we began the Antarctica project, Molly started by asking her students what they already knew about Antarctica. They charted basic information that they could contribute—cold, snow, penguins, continent, bottom of the earth etc. Most of the students participating were born in warm weather climates and had very little real-life experience relevant to these topics. Of the 60 students across 3 classes, fewer than 10 had first-hand experience with snow.

To build from this baseline, Molly showed the students videos of the conditions of Antarctica and brought in an Antarctic scientist who worked at a NASA research center nearby to speak with them. He offered first-hand accounts of his expeditions, let the students try on his gigantic weatherproof boots, and answered a never-ending stream of middle schooler questions. Molly also created presentations to increase student awareness of the essential contextual factors at play in Antarctica. At the time, Molly was new to design thinking but learning through experimenting with various classroom challenges. This process was enriched by library books, maps, primary sources from digital archives, hand-picked collections of digital resources, and student-curated digital content collections. Molly decided that she would try to find ways to connect students online with other scientists and experts who were willing to outreach to students.

At the end of the background building introduction, Molly's stage was created in the classroom. It had an Antarctica corner displaying the newly expanded knowledge of the context for which students were designing. Students continued to build on this corner throughout the Antarctica challenge, and it served as a visual representation and depository of the class' collective insights about this problem space.

Setting the Classroom Design Set

The Antarctica stage turned out to be an important space for the students during the challenge. The students visited, looked at the materials, and used them to justify or confirm their emerging ideas. Knowledge building spaces are already well known and desired in classrooms, especially when there is a major unit or topic to be studied or project work is about to take place. If you have a school library, the materials there and the librarians can be quite helpful. If your students are mature enough and have web access, the class can be building background and improving their search skills while developing some online space for background materials.

While the background building corner was important, it was one of several staging arrangements needed for accomplishing the design thinking challenge. Whether your design thinking topic is Antarctica, shelter, access to energy, community gatherings, or even improved lunches in the school cafeteria, the design thinking classroom demand...