![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Background, the Evolution of Today's Cleveland

How, then, did Cleveland's Hungarian community become what it is today? How does one measure an ethnic community when "being Hungarian" has different meanings for different people?

Mythology

Let us begin by dispelling a common myth about the "American Debrecen," i.e., that it was once the second largest Hungarian city, second only to Budapest. This statistic entered the popular mythology sometime early in the twentieth century and has been falsely perpetuated ever since. The facts do not quite justify the myth. According to the 1910 edition of the Révai Encyclopedia, the order of Hungarian cities by population was Budapest (881,604), Szeged (118,328), Debrecen (92,729), Pozsony (78,038, today known as Bratislava, Slovakia), Temesvár (72,555, Timisoara, Romania), Nagyvárad (64,169, Oradea, Romania), and Kolozsvár (60,808, Cluj, Romania). Steven Béla Várdy's research shows that at the same time Cleveland had a gross population of 364,463, with a little over 60,000 of the population being Hungarian. Thus Cleveland should be seventh or eighth on the list, or if one discounts Pozsony, Temesvár, Nagyvárad, and Kolozsvár as having other nationalities reflected in the population figures in addition to Hungarians, Cleveland still ranks only fourth on the list in 1910. However, 60,000 is still a significant number, and the myth did not evolve accidentally. But the facts show that Cleveland was never the second largest Hungarian city outside Budapest, despite common lore.

The Context of Cleveland

Cleveland is a rustbelt city, once known for its heavy industry, that in the late twentieth century saw economic decline and loss of population. Divided in two by the Cuyahoga river, its East Side tends to be slightly hilly, with the foothills of the Appalachian mountains not too far to the east, while the western side tends to be more flat, with the Great Plains stretching westward all the way to the Rocky Mountains. Its downtown, like many similar industrial northern cities, is mainly skyscrapers, office buildings, and stadiums, surrounded by a ring of working class neighborhoods and desolate ghettos, albeit with pockets of recent regentrification, and with mostly middle class suburbs in the outer rings. Places of significance to Hungarians are scattered throughout its downtown, inner city, and suburbs, reflecting the history and migration of its Hungarian population.

Like the Hungarians, other ethnic groups living in Cleveland also maintain their own traditions and culture. As a city of heavy industry such as steel and auto production, Cleveland attracted many blue collar workers throughout the years, not only from Eastern Europe but more recently from all over the world. Africans, Chinese, Croatians, Germans, Greeks, Indians, Irish, Italians, Japanese, Jews, Latvians, Lithuanians, Mexicans, Palestinians, Poles, Romanians, Russians, Serbs, Slovaks, and Ukrainians all maintain ethnic communities in and around Cleveland.

Immigrants from Ireland are by far the largest group. Their annual downtown parade on St. Patrick's Day, March 17, draws hundreds of thousands of participants and onlookers. Italians are the next largest in number—a neighborhood called Little Italy near University Circle has quaint cafes, restaurants, art galleries, bakeries, and an annual Columbus Day parade. For most members of these two groups, identity is mainly symbolic, as defined by sociologist Herbert Gans. The Germans have at least three cultural centers, with the Deutsche Zentrale park in the suburb of Parma, the Donauschwaben Kulturverein in Lenau Park in suburban Olmsted Falls, and the Sachsenheim in Cleveland proper. Another of the neighborhoods of Cleveland is known as Slavic Village and is home to numerous Polish, Slovak, and Czech churches, businesses and residents.

Most of Cleveland's ethnic groups, among them the Hungarians, no longer live in distinctly ethnic neighborhoods, but in the suburbs. Although some suburbs tend to contain higher concentrations of ethnic populations than others, such as Ukrainians in Seven Hills, Poles in Parma, Russians and Italians in Mayfield Heights, and Palestinians on the West Side, most nationalities are dispersed around the greater Cleveland area. Like the Hungarians, their churches also function as repositories of social traditions, and many of them house ethnic dance groups or weekend language schools, such as in the Greek, Serbian, Romanian and Ukrainian orthodox churches, or in Indian temples and Jewish synagogues.5

Recent collaboration among Cleveland's ethnic groups is also occurring, including www.ClevelandPeople.com, a website dedicated to the customs, cultural events, and various nationalities of Cleveland and northeast Ohio. This website lists recent events, with over 80 local ethnicities represented. On the business side, Global Cleveland is an initiative with the goal of regional economic development through actively attracting talented immigrants and other newcomers, hoping to welcome and connect them both professionally as well as socially.

The politician Dennis Kucinich, former mayor of Cleveland, former Congressional Representative, and a candidate for governor of Ohio in 2018, saw Cleveland's Hungarian population as one of the best organized, with its strengths being the number of organizations and its programs for children. He observed that Hungarians had a great influence on local politics up until the 1960s and 1970s, serving as a strong influence in local elections.

Geographically close to Cleveland lie several other communities with larger concentrations of Hungarians, including Fairport Harbor to the east, Lorain and Elyria to the west, Akron to the south, and Youngstown to the southeast. By and large these communities are self-sufficient, having mostly their own local traditions and events, though their members occasionally go to Cleveland to take part in social events. And while only a small minority of the population of these neighboring Hungarian communities understands and speaks the Hungarian language, they are nevertheless fiercely proud of their heritage. For them, Hungarian identity provides a sense of belonging to a local community that shares its Hungarian traditions worldwide.

The city of Cleveland, with a population of almost 400,000,6 is located in Cuyahoga County, named after the Cuyahoga River that flows into Lake Erie and divides the city east to west. Cuyahoga County also includes all the contiguous suburbs of Cleveland. Surrounding Cuyahoga County are five additional counties: Lorain County to the west, Lake County to the east, Medina County to the southwest, and Summit and Geauga counties to the southeast.7 Due to urban sprawl, these adjacent counties also include residents who identify with Cleveland (fans of Cleveland professional sports teams, workplaces downtown, etc.). Thus the entire Cleveland metropolitan area encompasses over 2 million residents, with approximately 1.2 million in Cuyahoga County (Cleveland and its adjacent suburbs).

Other Hungarian-American Cities

To a certain extent, Cleveland's Hungarian community bears resemblance to communities of Hungarians all across North America. Furthermore, its community shares characteristics of other émigré Hungarian communities worldwide. Visitors to established Hungarian communities most anywhere in the diaspora will find many parallels: in the midst of various other local foreign (Anglo-Saxon, or Latin American, or German) cultures and environments, language is maintained, culture is propagated through literature, lectures, music, folk dance, and often scouting, and culinary and holiday traditions are preserved and passed along to successive generations. These communities must work hard at promoting active participation and make an effort to maintain their ethnic origins, and their members spend countless volunteer hours, donating their time, labor, and money to ensure the success of their community institutions.

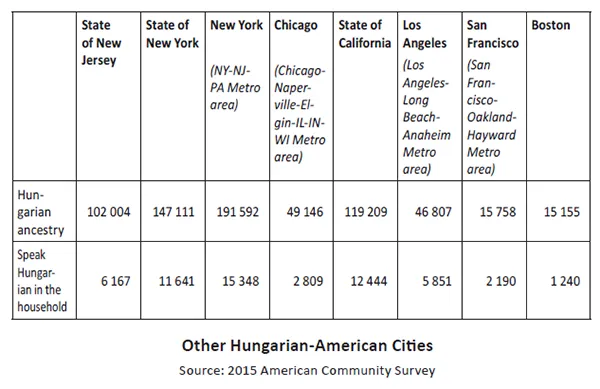

As an example, the city of New Brunswick, New Jersey, is the home of the corporate headquarters of Johnson & Johnson, the healthcare giant. Early in the twentieth century, New Brunswick's Hungarian population constituted two-thirds of the employees of Johnson & Johnson, and one third of all city residents. Today, a walkable neighborhood encompassing several city blocks is home to Catholic and Protestant Hungarian churches, a Hungarian Athletic Club, a scout center, and the American Hungarian Foundation, all of which own buildings and organize cultural activities for New Brunswick's Hungarian community. New Jersey had a total of 102,004 persons listing Hungarian ancestry and 6,167 persons speaking Hungarian in the home in the 2015 American Community Survey.

In New York City, Manhattan has a Hungarian church and a cultural center, the Magyar Ház on East 82nd Street. New York State had a total of 147,111 persons listing Hungarian ancestry and 11,641 persons speaking Hungarian at home in the 2015 American Community Survey. Chicago also has several Hungarian churches, a Hungarian scout troop, a weekend Hungarian school taught by volunteers, and numerous cultural activities held on an ongoing basis. Going further westward, California had a total of 119,209 persons listing Hungarian ancestry and 12,444 speaking Hungarian at home in the 2015 American Community Survey.

New Brunswick, New York City (191,592 of Hungarian ancestry and 15,348 speaking Hungarian in the household), Chicago (49,146 ancestry and 2,809 speakers), Los Angeles (46,807 ancestry and 5,851 speakers), and San Francisco (15,758 ancestry and 2,190 speakers), as well as older or smaller Hungarian communities such as in Buffalo, Detroit, Sarasota, Passaic (NJ), Portland, Seattle, or Washington, DC, and countless other North American cities, all have significant Hungarian communities, sharing similar characteristics, often with a Hungarian church in a crumbling neighborhood, and dinners and picnics and dances and language instruction. A newly vibrant community is in Boston, which in the last 15 years has seen a blossoming and expansion of its volunteer Hungarian cultural institutions that include a weekend language school, scout troop, lecture club, and other social events and groups. Indeed, its Metropolitan Statistical Area shows 15,155 people reporting Hungarian ancestry, with 1,240 speaking Hungarian in the house hold. But whether in Boston or Los Angeles, San Francisco or Chicago, New York, New Brunswick or Cleveland, for that matter, North American diaspora Hungarian communities have greater similarities than differences.

![]()

Waves of Hungarian Immigration

There have been six major waves of Hungarian immigration to Cleveland. The first arrived in the mid-1800s but did not have significant impact on the city. A much larger second wave, the óamerikás [old-timer] generation, built most of the physical landmarks of Hungarian Cleveland today, including establishing and actually building most of the Hungarian churches. The third wave arrived shortly after the Second World War and brought an intellectual bent to the cultural life. Émigrés of the 1956 Revolution comprised the fourth wave; their descendants either assimilated into American life or eased into existing Hungarian institutions. The fifth wave was comprised of economic refugees of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, and the final wave of Hungarian immigrants to Cleveland was part of the so-called brain drain: professionals arriving in the late 1990s through the present day. But how did it all start?

The first wave of Hungarian immigrants to Cleveland started even before the visit on January 31, 1852, of the great nineteenth century Hungarian statesman Lajos Kossuth. Two organizations requested his visit, the Hungarian Society of Cleveland and the Ladies Hungarian Society of Cleveland, and this relatively small wave of immigrants consisted mostly of freedom fighters from the 1848 Revolution. Thereafter came the first businessmen and entrepreneurs. Not many traces of these earliest Hungarian immigrants can now be seen in Cleveland, although their accomplishments and businesses were famous in their time. One of the most notable was Theodor Kundtz, born in 1852 in Metzenseifen (then in Hungary but due to shifting borders is now in Slovakia, and is called Medzev), who came to Cleveland as a penniless immigrant in 1873. He started his own manufacturing businesses specializing in wood products and by 1915 owned five large factories. In his hometown a descriptive phrase even originated because of Theodor Kundtz, known to his family as Tori: "Er hat es so gut wie Tori in Amerika [It's going well for him, just like for Tori in America].

The next wave of immigrants, coming in the latter part of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, built most of the Hungarian churches still standing today. They came primarily for economic reasons to escape the grinding poverty of the landless social strata of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Julianna Puskás estimated one half million emigrants from Hungary to the United States before the First World War; according to one estimate, 23 percent of those were people who had been to the United States before, staying for several years, earning money and then going back to Hungary. They found hardship in America as well, living in boarding houses and sharing a bed by sleeping in alternating shifts, but over half ended up staying and bettering their lives.8 They congregated around churches and built social institutions. Hungarians kept coming to America and to Cleveland up until the First World War. This group and their descendants are often referred to locally as öregamerikások or óamerikások [old timers].

The end of the First World War left Hungary dismembered from the treaty of Trianon, with 71.4 percent of historic Hungary's territory and 63.6 percent of its population suddenly under the jurisdiction of new countries.9 This upheaval in Hungary and its surrounding states caused a shift in attitude of many Hungarian-Americans: instead of viewing their stay in the United States as temporary and economic, many decided not to return home and began a transition to permanent residence, changing their lifestyles, attitudes, and value system. The percentage of Hungarian immigrants who became naturalized citizens virtually doubled from 28 percent in 1920 to 55.7 percent in 1930.10

A small group of political immigrants left Hungary after its short-lived communist dictatorship under Béla Kun in 1919, and a few Hungarian immigrants also arrived in America between 1933–1941. However, the restrictive immigration laws impo...