![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction The Promise of Green Building

Sustainability at its heart addresses the challenge of balancing the needs of people with the needs of nature. In many fields—from fisheries management to green business practice, for example—applying sustainable thinking has helped us to understand the limitations of natural systems and the dangerous demands that human systems are imposing on natural resources.

The lens of sustainability presents sobering news, telling us we must find alternatives to our Western, resource-gobbling ways. It would require six planets’ worth of resources to sustain the U.S. lifestyle at a global scale.

The media tend to focus on doom-and-gloom news, such as species loss, decreasing biological productivity of oceans, global climate change, and increasing pollution levels. While we cannot turn our back on negative trending of environmental indicators, what is needed is a more positive approach to the possibility of solving our ecological mess. As a society, we need a sense of hope and empowerment to energize people toward actions that make a difference. Sustainable building offers that hope—for design professionals, building officials, and the myriad of human beings that live and work inside buildings.

CLIMATE CHANGE AND GREEN BUILDING

On the global scale, green building has been identified as a key strategy for addressing climate change. As written in the U.S. Conference of Mayors Climate Protection Agreement, the goal of the agreement is to “meet or beat the target of reducing global warming pollution levels to 7 percent below 1990 levels by 2012.”1 One of the twelve key strategies in the statement says that these cities will “practice and promote sustainable building practices using the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED program or a similar system.”2

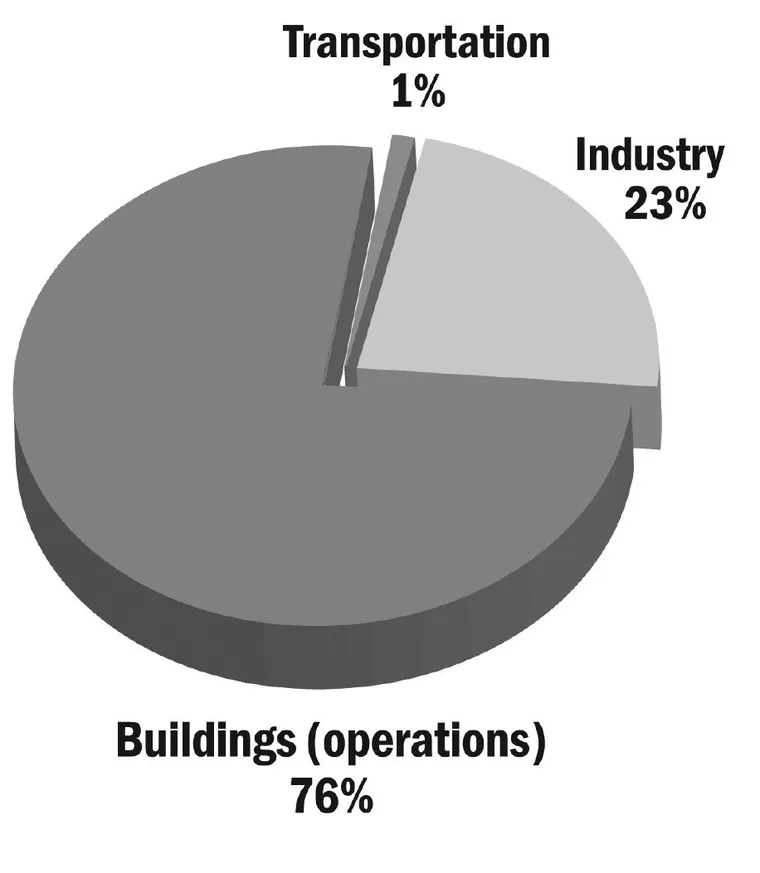

This latter statement acknowledges the significant portion of greenhouse gas emissions represented by the building sector. Using U.S. Energy Information Administration statistics, architect Ed Mazria has calculated that buildings account for a whopping 76 percent of the total U.S. electricity consumption. Mazria has thrown down the gauntlet by creating the 2030 Challenge, which sets a goal for all buildings to be greenhouse gas–neutral by the year 2030 (see figure 1.1). The U.S. Conference of Mayors unanimously adopted a 2030 Challenge resolution in 2006. In addition, as of mid-2009, more than 944 cities had signed on to the U.S. Mayors Climate Protection Agreement, representing over 83 million citizens.3 Such public declarations by elected officials provide a clear mandate for support of green building programs. When discussing with your elected officials why they should support green building, be sure to refer to such policy agreements.

FIGURE 1.1 U.S. Electricity Consumption

When the full impacts of buildings are included, they account for 76 percent of U.S. electricity use.

Credit: Image courtesy of http://www.architecture2030.org

A MOVEMENT WHOSE TIME HAS COME

The world of sustainable, or green, building is rapidly evolving. Until fairly recently, the modern-day built environment provided us with just a handful of grassroots examples of environmentally friendly buildings, and some of these may have been considered anomalies or, at the least, rather odd looking. Today, hundreds of more mainstream examples exist, ranging from college facilities to corporate headquarters to affordable housing. Just ten years ago, few firms, products, and sources of information were available. Today, the availability of information is expanding rapidly. In 2005, a Google search for “green building” resulted in more than six hundred thousand hits. In 2008, the same search results expanded to more than 5 million hits, and in 2009, to 7.3 million hits. Needless to say, there is a lot of information out there, but how do we make sense of it all to create green buildings that are both relevant and successful?

One goal of this book is to provide a mentoring tool for those endeavoring to create green building projects or programs in the public sector or within their organizations. While my experience is largely from ten years as the director of the Seattle green building program and from early work with the Austin green building program (see box 1.1), the tips and lessons provided in this book can be applied to other public jurisdictional authorities, such as at the county, state, or regional government level. In addition, some of the targeting strategies could be utilized by large corporations that develop, own, or manage a sizable building portfolio.

It is my hope that this book will provide valuable lessons and insights regarding the process of moving toward more sustainable buildings, cities, and organizations, with a particular focus on the public sector but with insights that can benefit many types of organizations. It should be instructive to the corporate sustainability officer, public policy maker, public or private building owner, project manager, architect, and student of green architecture.

BOX 1.1 THE VERY FIRST GREEN BUILDING PROGRAM

Doug Seiter, codeveloper of the City of Austin Green Building Program, former state coordinator for Built Green Colorado

In the mid-1980s, the City of Austin was engaged in building an aggressive energy-efficiency portfolio that included financial incentives (rebates), low-income residential assistance, and low-interest loans for energy retrofits. One entrée on that menu of programs was the New Residential Construction Program, which developed a nonregulatory relationship with Austin home builders. Austin Energy Star encouraged voluntary energy improvements with a three-star rating system and local promotion. This market-based approach became a vehicle for continual energy improvement through educating builders and consumers and stimulating competition within the industry. It also became a core strategy for introducing a broader approach to environmental building a few years later.

In 1989, I had reconnected with a nationally known local sustainability think tank, the Center for Maximum Potential Building Systems, codirected by Pliny Fisk III and Gail Vittori. Coincidentally, I was asked by my division manager, Mike Myers, to come up with ideas for a potential grant opportunity from the Energy Task Force of Public Technology Incorporated (PTI). I called the Center to bounce around some ideas, and it was during that exchange that Gail proposed to expand Austin’s successful Energy Star program to include other resource areas: water, materials, and waste. This built on a systems-based resource flow model that the Center had evolved over the prior decade. This more comprehensive method essentially laid the groundwork for a transformational approach to buildings and the environment, since energy was the principal focus of most building-related environmental initiatives at the time. With Austin Energy Star as a springboard for changing standard practices of mainstream builders and developers, Gail, Pliny, and I took this kernel of an idea and expanded it into a grant proposal to PTI. With a public-private partnership (the City of Austin and the Center for Maximum Potential Building Systems) as the driver, the proposal was accepted. We were off and running.

The Center was contracted to develop a framework for an environmentally based rating system with an initial focus on single-family residential construction. The resulting icon-based rating system, while comprehensive and based on the Center’s extensive systems and life cycle–oriented research, was ultimately replaced by a more simplified rating format. We at the City were about to take an environmental rating system to the Texas builders. Our experience with builders had been in the energy-efficiency realm, and in the mid-eighties, this was still a hard sell. To introduce the next layer of building considerations in the form of environmental consequences of building, we felt that an incremental approach would be needed to get us in the door. Even so, as I look back at that first rating system, the list was certainly pushing the envelope.

The Austin Green Builder Program emerged (the name was later revised to the Austin Green Building Program). To our knowledge, it was the first green building program in the world. The world, it seems in retrospect, was ready for this more systems-based, albeit simplified, market-ready approach than was initially conceived. At the 1992 U.N. Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, the City of Austin’s Green Building Program was recognized as one of twelve exemplary local environmental initiatives—and the only recipient from the United States. The following year, David Gottfried, Rick Fedrizzi, and Mike Italiano founded the U.S. Green Building Council, acknowledging Austin’s Green Building Program as one of the inspirations to establish a nationally based organization to advance green building. In just a few short years, the term green building had entered the public lexicon. USGBC’s work on LEED began in 1995, further building off of the inspired conceptual framework that sparked Austin’s ground-breaking initiative. And, as they say, the rest is history.

SOLUTIONS, NOT PROTESTS

The success of green building appears to be outpacing many other environmental movements. Renowned geneticist David Suzuki, named one of the 2007 “Heroes of the Environment” by Time magazine along with Al Gore, Robert Redford, and Wangari Maathai, expresses amazement at the adoption and progress of the sustainable building movement’s transformation of the marketplace, compared to many other environmental movements. Suzuki is also impressed with the size and participation level of the community pushing the movement forward.4 This success may be partly because green building differs from reactive movements oriented solely around protest. It provides a proactive solution to a complex web of problems, long-term profitability, and a positive approach people can get behind. Green building creates visible symbols and visceral experiences for how a sustainable world might look and feel, further feeding inspiration in the movement and an increase in supporters.

Leaders in the field have found ways to leverage their agenda within the building industry because of the tremendous resources already invested in design and construction activities. Most of the building projects that end up becoming green are development that is slated to happen anyway. With the appropriate vision, tools, and leadership, these resources can be shifted toward green rather than conventional building. Capital dollars and design team creativity can be captured to create increased levels of ecological integrity in the built environment. Green buildings can become generators, rather than consumers, of power and other resources. This turns the traditional paradigm for grid-dependent and minimum code-compliance building on its head.

SUSTAINABILITY GOES CORPORATE

Hand in hand with the maturation of the green building movement, sustainable business practices are becoming a key corporate value. Many Fortune 500 companies are now also rated on their corporate reputation for sustainability, including social factors, community and environmental responsibility, innovation, and quality of goods or services. Research is beginning to show that high marks related to sustainability issues can be directly correlated with corporate profitability. Never before has the understanding been clearer that our ecological prosperity is linked to our economic prosperity.

Green facility development, ownership, and tenancy are now understood as a key aspect of smart business practice. Consider the many examples. Toyota Motor Corporation not only markets hybrid automobiles such as the Prius but is also building green buildings to house its own employees. Toyota Motor Sales division’s campus headquarters building in Torrence, California, uses a combination of strategies, including solar power, recycled water use, and high-efficiency equipment. The building outperforms Toyota’s required 10 percent return on investment, reduces potable water use by 60 percent, and reduces energy use by 60 percent over code.5 That all adds up to significant operational savings and an award-winning building that has received excellent media coverage, the latter of which also generates corporate value.

Yoshi Ishizaka, senior managing director of Toyota, seems to understand how all this not only protects the company’s bottom line but also embodies a new business ethic. According to Ishizaka: “It is our actions today that determine the world of tomorrow. The results of those actions will directly affect the world that our children inherit.”6 Toyota is emblematic of a growing number of corporations that have enthusiastically embraced the green building concept as central to their good business practices. Governments, too, share many characteristics with corporate organizations. They develop, own, and manage facilities. They seek to protect the value of their assets and are concerned with risk management. They employ large numbers of people and share corporate concerns about employee performance, retention, and overhead.

WHY CITY GOVERNMENT?

Few entities hold more power to transform the face of urban environments than do city governments. These municipal jurisdictions define the boundaries of urban environs; permit building projects; provide critical safety, environmental, and social services; and are often the single largest owners of urban space, including public lands and rights-of-way. In addition, cities can often be large users of private architectural design and construction services. As major public developers and landholders, cities such as Seattle are significant players in the real estate marketplace. They can serve as clients for a huge number of design, construction, and development service contracts, with large market value. Not only is this impact seen in the architectural services arena, but the public works that result have a huge impact on the enduring fabric of the city. Green government facilities send a message to the public, who help to fund, and eventually visit, these places.

The City of Seattle, for example, owns over one thousand buildings, totaling nearly 7 million square feet. The operational impacts of maintaining these buildings are huge. In addition, it owns and manages 2.5 million square feet of parking and yard space, and nearly 215 million square feet of green and open space.7 The City also owns the electric, water, and solid waste utilities that set utility rates and provide conservation incentives. The City permits land and building development within the city limits. As the keeper of the keys for building codes and most utility services, the City wields tremendous power over the building sector and the built environment.

As the first entity to formally adopt LEED™ (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) standards, the passage of Seattle’s sustainable building policy in February 2000 sent ripples through the public and private sectors. The an...