![]()

CONTENT LIST

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Introduction to mise en scène

1.3 Production design: sets, props and costumes

1.4 Lighting

1.5 Performance

1.6 Sound and music

1.7 Framing: position; depth of field; aspect ratio; height and angle

1.8 Camera movement

1.9 Editing

1.10 Intensified continuity

1.11 Conclusion

1.1 INTRODUCTION

The way we learn to understand films is almost through a process of osmosis; we seem to absorb the rules in such a way that we don’t even think about how we come to understand what’s happening on the screen. Unsurprisingly film does have a language, though maybe not one as strictly structured as that which governs the use of words; this hasn’t stopped film theorists from trying to unearth the underlying grammar of the medium. The purpose of this chapter is to understand the conventional use of film language.

The chapter will focus, in the main, on the language of conventional cinema, though it should be noted that these codes and conventions only became dominant because of Hollywood’s economic might. It would be interesting to know how many of us, in the west at least, learned film language through watching Disney films. The films considered will be mostly contemporary, as the reader is more likely to be familiar with them. There will also, however, be reference to films regarded as ‘classics’. In order to fully appreciate the medium of film it is necessary to look beyond the mainstream, beyond Hollywood and beyond films made in the reader’s lifetime.

Although the chapter deals with many elements in isolation, it should never be forgotten that meaning in film is created through a combination of all the codes and conventions of film language. In addition, the context (of both the film’s narrative and the society in which the film was created) in which these elements are placed is crucial to our understanding. That said, for pedagogical purposes it is useful to split film language into many of its constituent parts. We shall begin with an examination of mise en scène, what’s ‘in the picture’, before considering the formal elements of camera position and movement. At the end of the chapter we will look at editing and how a film’s stars contribute to the way meaning is created.

1.2 INTRODUCTION TO MISE EN SCÈNE

Miseenscène is the starting point for analysis of ‘film as film’ (the title of a ‘classic’ introduction to film analysis, Perkins, 1972) as distinct from film in its social context. First used by critics in Cahiers du Cinéma in the 1950s, mise en scène analysis focuses on what can be seen in the scene. For most of the twentieth century what was being filmed, the pro-filmic event, had to exist in front of the camera; so otherworldly objects, such as StarWars’ (US, 1977) Death Star, were models. However, the creation of computer-generated imagery (CGI) has altered our understanding of the cinematic image. For example, at the start of Prometheus (US-UK, 2012) the camera moves towards the body of the alien and then, in the same shot, moves inside the body. Such a shot would have been impossible in this form before CGI (seefl9.9).

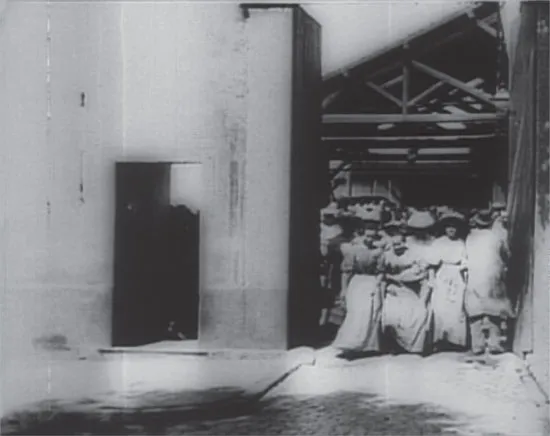

The mise en scène of the first film ever projected, the Lumière brothers’ Workers Leaving the Lumière (La Sortie des usines Lumière à Lyon, France, 1895), consisted of a factory gate being opened and the workers exiting (see Still 1.1). This was an ‘actuality’, a proto-documentary,

which showed events, without apparent narrative, for the length of time that the film lasted (around one minute). The content of ‘actualities’ was less important than the novelty of the moving pictures. The Lumières’ films, and their rival, (American) Edison’s Kinetoscope, both began ‘with a still image which then started to move’ (Christie, 1994: 10a, emphasis in original), emphasizing the ‘miracle’ of the moving picture.

STILL 1.1 The first film projected showed workers leaving a factory in Workers Leaving the Lumière

In the early days of cinema the creation of impossible worlds was also evident, most famously in the films of Louis Méliès; such as A Trip to the Moon (Le Voyage dans la lune, France, 1902). However Méliès had to completely fabricate the pro-filmic event by shooting in his studio, memorably re-created in Martin Scorsese’s Hugo (US, 2011). From the start of film history the dichotomy of realism (of the Lumières) versus (Méliès’s) fantasy was evident.

While early films obviously had a mise en scène, the way they were structured is very different from today’s narrative cinema. They were ‘tableau films’ consisting of a succession of scenes filmed in a long shot, square on to the action. The Armenian film The Colour of Pome-granates (Sayat Nova, Soviet Union, 1968) is a rare example of the tableau film made after the early days of cinema. For tableau films the mise en scène is carrying almost all of the narrative information; however, what the defining features of mise en scène are is open to debate.

For some writers the pro-filmic event defines mise en scène. For example, in the first edition of the classic text Film Art (1979), David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson state that mise en scène consists of setting, lighting, costume and figure expression and movement (that is, the characters’ behaviour and movement in the scene); they consider camera placement (framing) in a separate chapter. Bruce Kawin’s definition (1992), however, also includes

choice of filmstock (black-and-white or color,ñe-grain or grainy) … aspect ratio (the proportion of the screen) … framing (how much of the set or cast will be shown at a time) … camera placement and movement, and … sound environment.

(Kawin, 1992: 98)

Arguably, by including the formal elements of filmstock, framing and aspect ratio, Kawin’s definition is too unwieldy. However, including sound as part of mise en scène makes sense, as there seems little point in divorcing aural elements emanating from a scene from the visual. This is a question of definition and it matters little, when analysing film, whether you consider camera positioning as part of mise en scène or not, as long as you do consider all the elements at some point. As you will find in the analyses below, it’s difficult to focus on the categories in isolation, so we shall include lighting, for example, when discussing set design.

I agree with Kawin’s inclusion of camera placement because the position can transform the way audiences see the pro-filmic event and I will include diegetic (that is, ‘from the narrative world’; see below) sound in our definition. Although camera movement changes the way we see the pro-filmic space, it also draws attention to itself and so awareness is split between what is ‘in the scene’ and how the camera is transforming what we see. For our purposes mise en scène refers to the still image, with diegetic sound; movement will be considered separately. The formal elements of filmstock (see 9.3) will only be considered as part of mise-encène if it is making an expressive point, even though it is exterior to it. From our perspective we shall consider images created by a computer as much as part of the mise en scène as the images that actually existed in front of the camera during filming.

So mise en scène consists of:

production design: sets, props and costumes

colour (present in both production design and lighting)

actors’ performance (including casting and make-up) and movement (blocking)

diegetic sound (that is, sound that emanates from the scene and is not extraneous to it, such as the music that is not being played within the scene or a voice-over)

framing, including position; depth of field; aspect ratio; height and angle (but not movement).

As we shall see, in mainstream cinema mise en scène is designed to both create the narrative space and help progress the narrative (see Still 1.2).

STILL 1.2 The mise en scène emphasizes the immature nature of Nina with the pink teddies in the background...