The Dark Path and the Bright Lane

There are two very different ways or approaches to thinking about God. The first way is like a slippery, sloping cliff-top goat path. On a stormy, moonless night. During an earthquake. It is the path of trying to work God out by our own brainpower. I look around at the world and sense it must have all come from somewhere. Someone or something caused it to be, and that someone I will call God. God, then, is the one who brings everything else into existence, but who is not himself brought into being by anything. He is the uncaused cause. That is who he is. God is, essentially, The Creator, The One in Charge.

It all sounds very reasonable and unobjectionable, but if I do start there, with that as my basic view of God, I will find every inch of my Christianity covered and wasted by the nastiest toxic fallout. First of all, if God’s very identity is to be The Creator, The Ruler, then he needs a creation to rule in order to be who he is. For all his cosmic power, then, this God turns out to be pitifully weak: he needs us. And yet you’d struggle to find the pity in you, given what he’s like. In the aftermath of World War II, the twentieth-century Swiss theologian Karl Barth put it starkly:

Perhaps you recall how, when Hitler used to speak about God, he called Him “the Almighty”. But it is not “the Almighty” who is God; we cannot understand from the standpoint of a supreme concept of power, who God is. And the man who calls “the Almighty” God misses God in the most terrible way. For “the Almighty” is bad, as “power in itself” is bad. The “Almighty” means Chaos, Evil, the Devil. We could not better describe and define the Devil than by trying to think this idea of a self-based, free, sovereign ability.[1]

Now Barth was absolutely not denying that God is Almighty; but he wanted to make very clear that mere might is not who God is.

The problems don’t stop there, though: if God’s very identity is to be The Ruler, what kind of salvation can he offer me (if he’s even prepared to offer such a thing)? If God is The Ruler and the problem is that I have broken the rules, the only salvation he can offer is to forgive me and treat me as if I had kept the rules.

But if that is how God is, my relationship with him can be little better than my relationship with any traffic cop (meaning no offense to any readers in the police force). Let me put it like this: if, as never happens, some fine cop were to catch me speeding and so breaking the rules, I would be punished; if, as never happens, he failed to spot me or I managed to shake him off after an exciting car chase, I would be relieved. But in neither case would I love him. And even if, like God, he chose to let me off the hook for my law-breaking, I still would not love him. I might feel grateful, and that gratitude might be deep, but that is not at all the same thing as love. And so it is with the divine policeman: if salvation simply means him letting me off and counting me as a law-abiding citizen, then gratitude (not love) is all I have. In other words, I can never really love the God who is essentially just The Ruler. And that, ironically, means I can never keep the greatest command: to love the Lord my God. Such is the cold and gloomy place to which the dark goat path takes us.

The other way to think about God is lamp-lit and evenly paved: it is Jesus Christ, the Son of God. It is, in fact, The Way. It is a lane that ends happily in a very different place, with a very different sort of God. How? Well, just the fact that Jesus is “the Son” really says it all. Being a Son means he has a Father. The God he reveals is, first and foremost, a Father. “I am the way and the truth and the life,” he says. “No one comes to the Father except through me” (Jn 14:6). That is who God has revealed himself to be: not first and foremost Creator or Ruler, but Father.

Perhaps the way to appreciate this best is to ask what God was doing before creation. Now to the followers of the goat path that is an absurd, impossible question to answer; their wittiest theologians reply with the put-down: “What was God doing before creation? Making hell for those cheeky enough to ask such questions!” But on the lane it is an easy question to answer. Jesus tells us explicitly in John 17:24. “Father,” he says, “you loved me before the creation of the world.” And that is the God revealed by Jesus Christ. Before he ever created, before he ever ruled the world, before anything else, this God was a Father loving his Son.

“HE STOOD FOR THE TRINITARIAN DOCTRINE”

At the beginning of the fourth century, in Alexandria in the north of Egypt, a theologian named Arius began teaching that the Son was a created being, and not truly God. He did so because he believed that God is the origin and cause of everything, but is not caused to exist by anything else. “Uncaused” or “Unoriginate,” he therefore held, was the best basic definition of what God is like. But since the Son, being a son, must have received his being from the Father, he could not, by Arius’s definition, be God.

The argument persuaded many; it did not persuade Arius’s brilliant young contemporary, Athanasius. Believing that Arius had started in the wrong place with his basic definition of God, Athanasius dedicated the rest of his life to proving how catastrophic Arius’s thinking was for healthy Christian living.

Actually, I’ve put it much too mildly: Athanasius simply boggled at Arius’s presumption. How could he possibly know what God is like other than as he has revealed himself? “It is,” he said, “more pious and more accurate to signify God from the Son and call Him Father, than to name Him from His works only and call Him Unoriginate.”a That is to say, the right way to think about God is to start with Jesus Christ, the Son of God, not some abstract definition we have made up like “Uncaused” or “Unoriginate.” In fact, we should not even set out in our understanding of God by thinking of God primarily as Creator (naming him “from His works only”)—that, as we have seen, would make him dependent on his creation. Our definition of God must be built on the Son who reveals him. And when we do that, starting with the Son, we find that the first thing to say about God is, as it says in the creed, “We believe in one God, the Father.”

That different starting point and basic understanding of God would mean that the gospel Athanasius preached simply felt and tasted very different from the one preached by Arius. Arius would have to pray to “Unoriginate.” But would “Unoriginate” listen? Athanasius could pray “Our Father.” With “The Unoriginate” we are left scrambling for a dictionary in a philosophy lecture; with a Father things are familial. And if God is a Father, then he must be relational and life-giving, and that is the sort of God we could love.

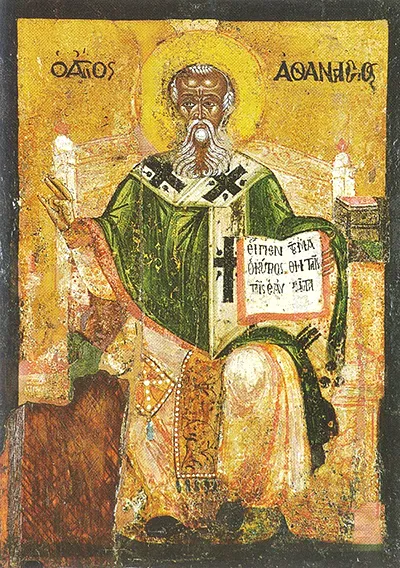

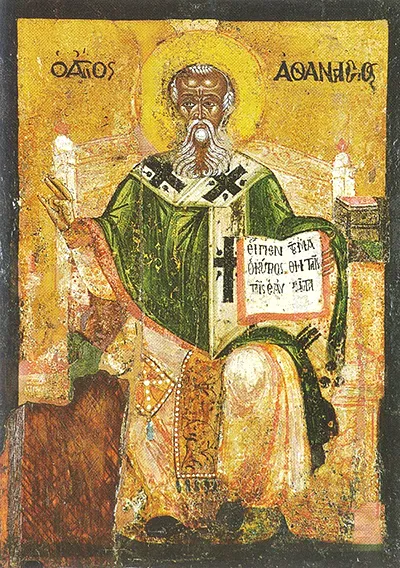

Icon of St. Athanasius (296?-373)

The Loving Father

The most foundational thing in God is not some abstract quality, but the fact that he is Father. Again and again, the Scriptures equate the terms God and Father: in Exodus, the Lord calls Israel “my firstborn son” (Ex 4:22; see also Is 1:2; Jer 31:9; Hos 11:1); he carries his people “as a father carries his son” (Deut 1:31), disciplines them “as a man disciplines his son” (Deut 8:5); he calls to them, saying: “As a father has compassion on his children, so the Lord has compassion on those who fear him” (Ps 103:13) and “‘How gladly would I treat you like sons and give you a desirable land, the most beautiful inheritance of any nation.’ I thought you would call me ‘Father’ and not turn away from following me” (Jer 3:19; see also Jer 3:4; Deut 32:6; Mal 1:6).

Isaiah thus prays, “You are our Father, . . . you, O Lord, are our Father” (Is 63:16; see also Is 64:8); and a popular Old Testament name was Abijah (“The Lord is my father”). Then Jesus repeatedly refers to God as “the Father” and directs prayer to “our Father”; he tells his disciples he will return to “my Father and your Father, to my God and your God” (Jn 20:17); Paul and Peter refer to “the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ” (Rom 15:6; 1 Pet 1:3); Paul writes of “one God, the Father” (1 Cor 8:6), of “God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ” (1 Cor 1:3); Hebrews counsels: “God is treating you as sons. For what son is not disciplined by his father?” (Heb 12:7).

Since God is, before all things, a Father, and not primarily Creator or Ruler, all his ways are beautifully fatherly. It is not that this God “does” being Father as a day job, only to kick back in the evenings as plain old “God.” It is not that he has a nice blob of fatherly icing on top. He is Father. All the way down. Thus all that he does he does as Father. That is who he is. He creates as a Father and he rules as a Father; and that means the way he rules over creation is most unlike the way any other God would rule over creation. The French Reformer John Calvin, appreciating this deeply, once wrote:

We ought in the very order of things [in creation] diligently to contemplate God’s fatherly love . . . [for as] a foreseeing and diligent father of the family he shows his wonderful goodness toward us. . . . To conclude once for all, whenever we call God the Creator of heaven and earth, let us at the same time bear in mind that . . . we are indeed his children, whom he has received into his faithful protection to nourish and educate. . . . So, invited by the great sweetness of his beneficence and goodness, let us study to love and serve him with all our heart.[2]

It was a profound observation, for it is only when we see that God rules his creation as a kind and loving Father that we will be moved to delight in his providence. We might acknowledge that the rule of some heavenly policeman was just, but we could never take delight in his regime as we can delight in the tender care of a father.

So what does it mean that God is a Father? Well, first of all, it does actually mean something. Not all names do. My dog is called Max, but that doesn’t really tell you anything about him. The name doesn’t tell you what he is or what he’s like. But—if I can make the jump—the Father is called Father because he is a Father. And a father is a person who gives life, who begets children. Now that insight is like a stick of dynamite in all our thoughts about God. For if, before all things, God was eternally a Father, then this God is an inherently outgoing, life-giving God. He did not give ...