Introduction

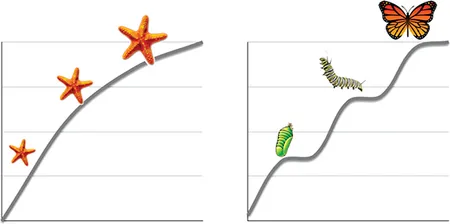

Every developmental psychologist works within a theoretical perspective, a lens through which to look at the child. At times the perspective is explicitly stated, at other times it is implicit and unspoken. Each perspective includes assumptions about the processes of human development, the roles of nature and nurture in development, whether development is a continuous or a discontinuous process (see Figure 1.1), what causes individuals to differ from one another in their psychological characteristics, and the appropriate ways to conduct research.

Over the past one hundred years, roughly the time that psychology has existed as a recognized science, developmental psychology has passed through five broad theoretical perspectives. In this chapter I summarize each in turn, highlighting some important people in each, and then compare them. The five perspectives, and the span of greatest influence for each, are as follows:

- Genetic psychology: 1890s–1950s

- Behaviorism: 1930s–1950s

- Cognitive developmental psychology: 1957–today

- Constructivism: 1950s–today

- Cultural psychology: 1980s–today

DescriptionFigure 1.1 Continuous and discontinuous development

1.1 Genetic Psychology

When psychology first became a discipline separate from philosophy, at the end of the nineteenth century, the study of child development had a central place. The predominant theoretical perspective placed emphasis on endogenous factors: influences inside the child. The study of children’s growth and development was called “genetic psychology,” where the term “genetic” referred not to the genes (nothing was known about chromosomes at that time) but to a focus on origins.

1.1.1 Granville Stanley Hall

Granville Stanley Hall (1844–1924) was the first person to obtain a doctoral degree in psychology in the United States (studying with William James at Harvard University). Hall was one of the more colorful people in the history of developmental psychology, and he is credited with initiating the systematic study of children’s development. Hall became the founder of the American Psychological Association, and its first president. He traveled extensively and studied in Europe, taught at Harvard University and Johns Hopkins University, and became president of Clark University.

Hall was influenced by both Sigmund Freud and Charles Darwin. In his view, a child’s development involves recapitulation: the individual relives the evolutionary stages of the history of their “race.” For Hall, a child’s development is biological not in the sense of resembling the blossoming of a flower, but because the individual traces a pathway that was first defined by the evolution of the species. In his view “the child and the race are each keys to the other.”

Today we know that all the humans on planet Earth are very similar genetically. There is no evidence to support the idea of biologically distinct races. But Hall was writing at a time when this fact was not known, and he insisted that psychologists should search for the traces, the fossils, of earlier forms of our “soul life.” This was, after all, Darwin’s method: to describe the anatomical traces of earlier creatures in those living today, as well as in the fossils of extinct species. For Hall, it is not a child’s society or culture that defines how she will grow up, but her biological inheritance, and in his view this reflects her race.

Hall believed that the habits and codes of conduct of their ancestors are the source of modern humans’ temperamental dispositions, our “instinct-feelings.” He proposed that human development operates on these dispositions, on a level deeper than that of intellect.

It might seem that Hall was a determinist, believing that psychological development is completely determined by heredity. But in fact he was quite aware of the interaction between organism and environment. Indeed, Hall was worried that in certain environments psychological growth can become too rapid and unnatural: our “unbalanced, hot-house life … tends to ripen everything before its time” (Hall, 1904, p. xi). He also wrote of the ways civilization represses and corrupts development; he believed that modern life creates, in his famous phrase for the turbulence of adolescence, too much “storm and stress.”

For Hall, then, culture is not a resource for psychological development but a source of corruption. He considered it important to search for “true norms against the tendencies to precocity …” (1904, p. viii). Listening to the echoes of the “vaster, richer life of the remote past of the race” might save us from this “omnipresent danger of precocity” (1904, p. xi).

Consequently, Hall did not believe that humans have a biologically fixed nature. On the contrary, he wrote that “Man is rapidly changing,” and “man is not a permanent type but an organism in a very active stage of evolution toward a more permanent form” (1904, p. vii). In his view the laws of human growth might be fixed, but humans are continually changing as a result of those laws. The human species, in fact, is “still adolescent in soul.”

Hall viewed child development, then, as a passage through developmental stages which corresponded with stages in the evolution of the child’s “race.” The period of infancy and early childhood resembles, in Hall’s eyes, the time of our remote animal ancestors. Middle childhood corresponds to what he called the “pigmoid” stage of evolution—an age, in his view, at which the child enjoys activities such as hunting, fishing, fighting, roving, idleness, and playing. The country is the proper environment for a child of this age, and “Books and reading are distasteful, for the very soul and body cry out for a more active, objective life, and to know nature and man first hand.”

Adolescence, in contrast, is “a marvelous new birth” (1904, p. xv) when “the higher and more completely human traits” appear (1904, p. xiii). Nature “arms youth for conflict”; in adolescence we see the changes that make men aggressive and prepare women for maternity. Adolescence is the time of a “reconstruction” and a changing of the relations among “psychic functions.” Sex now “asserts its mastery” and “works its havoc” (1904, p. xv). The adolescent “craves more knowledge of body and mind”; he “wakes to a new world and understands neither it nor himself.” These new powers must be “husbanded and directed,” for at this age “everything is plastic” (1904, p. xv).

1.1.2 Arnold Gesell

Another significant figure in the genetic perspective, a generation later than G. Stanley Hall, was Arnold Gesell (1880–1961). Gesell worked at the Yale University Clinic for Child Development. Where Hall was a Romantic, Gesell, in contrast, was interested in the rational, ordered, and self-disciplined aspects of human nature. For him, the scientific study of children’s development should be based on empirical facts, not on images of a distant life of the soul.

Despite their differences, Gesell, like Hall, emphasized the role of biological maturation in children’s development. In an article written for the Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences Gesell proposed that development is essentially growth: “Growth is itself a unifying concept which removes undue distinctions between mind and body, between heredity and environment, between health and disease and also between separate scientific disciplines” (Gesell, 1930, pp. 392–393). He also stated that “like the heavenly bodies the human life cycle is governed by natural laws. In surety and precision the laws of development are comparable to those of gravitation” (1943, p. 59). In his view, the phenomena of growth “are subject to general and unifying laws which can be formulated only by coordinated contributions from several scientific domains” (1930, p. 392).

Gesell viewed development as a movement through distinct stages, but he insisted that it proceeds not “in a staircase manner or by installments. It is always fluent and continuous” (Gesell et al., 1943, p. 61). He saw development as the result of an interaction between child and environment. However, the basic characteristics of each developmental stage are, in his view, the products of an evolutionary process in which new qualities are acquired and then handed down.

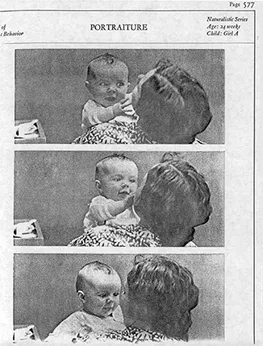

Although Gesell emphasized that the infant “is a biological fragment of nature,” he saw that “he is also meshed in a web of human relationships,” and maintained that “the system of child psychology which any culture achieves is an index of that culture.” He proposed that child psychology leads to “a deeper comprehension of the process of social organization itself.” Gesell himself undertook a series of highly detailed studies of children’s development and put children under the microscope—or at least under the film camera. His laboratory housed a dome under which children of different ages were observed objectively and filmed for detailed analysis of their behavior.

Figure 1.2 Photos from Gesell’s (1934) Atlas of Infant Behavior reprinted with permission from APA

Gesell thought of the scientific disciplines of psychology and biology as linked, in a scientific division of labor. He envisioned psychology becoming psychobiology, and producing a “psychotechnology” of testing and assessment. In time, he predicted, “the early span of human growth will come more fully under social control,” and “this is only the beginning of a policy of health supervision.” In his view, then, the goal of scientific developmental psychology was to discover laws of growth to achieve “a constructive and preventive supervision of human infancy” (1930, p. 393). He believed that, “With the employment of scientific method, however, errors are being steadily reduced and the manifold problems of child development are approached in a new spirit of rationalism” (1930, p. 391).

1.1.3 Erik Erikson

Another key figure whose work had its roots in the genetic perspective, though it moved beyond this perspective, was Erik Erikson (1902–1994), who trained as a Freudian psychoanalyst at the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute. After moving from Europe to the USA Erikson worked to articulate a “psychosocial” model of development, which expanded Freud’s psychosexual account of children’s development to include attention to the culture in which a child develops. He wanted to create a psychoanalysis that was “sophisticated enough to include the environment” (Erikson, 1994b[1968], p. 24).

Erikson viewed human development as a life cycle that passes through distinct stages. Each stage has its own dynamics, the result of “the laws of individual development and of social organization” (Erikson, 1994a[1959], p. 7). In addition, each stage involves a distinct kind of crisis. By “crisis” Erikson meant “a necessary turning point, a crucial moment, when development must move one way or another, marshaling resources of growth, recovery, and further differentiation” (1994b[1968], p. 16). He proposed that every stage involves a culturally defined “moratorium” (a temporary delay) during which the individual is given time to master the challenges of that stage, and during which social institutions provide guidance. Each moratorium is a period during which the potential crisis of the stage can be resolved. If the crisis is not resolved, there will be challenges for future development.

Erikson...