Concepts of Social Justice, Inclusion, Equality and Human Rights

What is inclusion?

Inclusion, a concept which has diverse origins, draws upon a range of perspectives. Influenced by different international governments, non-government agencies, professional groups, communities and activists, over many decades, means the concept of inclusion is often interpreted in various ways by individuals and organisations (Devarakonda 2013). Many advocates of inclusion locate their philosophy on arguments of social justice, where ‘commitments to equality and diversity are not just respected ideas but enacted practices’ (Gibson 2009: 1). However, doing inclusion in practice is not always straightforward and it is often loaded with tensions and complexities.

Activity Thinking about inclusion

When you consider the term ‘inclusion’ with regards to children and families, what do you think about?

You may have identified some of the principles below. Working with a peer, select three principles and explain why each is essential in the work undertaken with young children.

Principles of inclusion (not an exhaustive list)

- Values (equality, respect, tolerance, fairness); justice; human rights; individual needs; diversity; participation; empowerment; including marginalised groups; challenging stereotypes, prejudice, discrimination and barriers; policies and practices.

It is important that early years practitioners and teachers are aware of the broader picture which influences inclusive ideology underpinning policy, practice and provision within their settings. Inclusive education, which is centred around issues of difference and identity, and has led to a ‘unified drive towards minimal exclusion … through the removal of exclusionary factors’ (Nutbrown and Clough 2013: 8) within schools and early years provision, is a sub-set of the wider area of social inclusion.

Social exclusion describes the phenomenon where certain individuals or groups ‘have no recognition by, or voice or stake in, the society in which they live’ (Charity Commission 2001: 2). The causes are often multiple and connected to various social factors, frequently including financial hardship, and lead to many marginalised families struggling with social, economic and political aspects in their lives. Social inclusion results from positive action taken to change the factors that have led to social exclusion, enabling individuals or communities to fully participate in society (Charity Commission 2001).

Human rights and social justice

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) was established in 1989 and consists of 54 articles that ‘set out the civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights’ that governments should make available to all children (UNICEF UK, 2020). Central to this is the acknowledgement that every child under the age of 18 has basic rights, which include: the right to life, survival and development; protection from violence, abuse or neglect; health care; education; being raised by, or have a relationship with, their parents; and having their views acknowledged (Save the Children 2020). Globally, many governments have signed the Convention, agreeing that they will meet the rights outlined and help all children to reach their full potential. Although the UNCRC itself is not legally binding, many of its articles are covered by legislation in the UK, which if breached can lead to penalties.

Despite the UK having signed up to the UNCRC, many children in the country experience living conditions which impact on their basic rights. In 2016, the committee reporting back on the UK's implementation of the UNCRC expressed concern that many children with disabilities are still placed in special schools or special units in mainstream schools and that bullying remains a widespread problem, particularly against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex children, children with disabilities and children belonging to minority groups, including Roma, Gypsy and Traveller children. It recommended that sexual and reproductive health education should be made part of the mandatory school curriculum; that increased investment is needed to reduce child poverty, support children's mental health and strengthen the rights of asylum-seeking, refugee and migrant children; and that the UK should implement comprehensive measures to further develop inclusive education (Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education [CSIE] 2018a; Equality and Human Rights Commission [EHRC] 2019a).

Human rights and social justice, which underpin policy and practice within schools and early years provision in the UK, are essential to the care and education of children and young people. However, it is not always easy for practitioners to translate rights policy into effective practice. Rights and values underpinning social justice are complex as different principles may apply in different situations (Smith 2012) and individuals will have different opinions as to what they consider to be fair and just. Ruitenberg and Vokey (2010 cited in Smith 2012) conceptualise three principles of justice:

- Justice as harmony – asserts that people have different talents which, when combined, strengthen a community and society. Therefore, practitioners should treat children differently to support individual talents, enabling children to reach their own potential.

- Justice as equity – based on the belief that children need to be treated differently according to what they need to enable them to reach a certain level of achievement or outcome.

- Justice as equality – the belief that although children are not the same, they are equally deserving, so should be treated the same. Criticisms against this principle are that children are individuals with different needs and therefore need to be treated differently; and treating everyone the same will mean children with difficulties will struggle and capable children will be unable to excel.

Equality of opportunity

The Equality Act 2010 replaced nine major pieces of legislation and numerous regulations relating to various forms of discrimination. It provides a single law, covering all the types of discrimination that are unlawful. The Act places a legal duty on public bodies (including schools and early years settings) to promote equality of opportunity and to protect the rights of individuals, including protection against discrimination. It highlights nine protected characteristics: sex, race, religion or belief, sexual orientation, disability, age, gender reassignment, pregnancy and maternity, and marriage and civil partnership. The Act also states there must be protection for people discriminated against because they are ‘perceived’ to have, or are ‘associated’ with someone who has, a protected characteristic. The Public Sector Equality Duty places an extra duty on public bodies, to consider how they can: eliminate discrimination and other conduct that is prohibited by the Act; advance equality of opportunity between people who share a protected characteristic and people who do not share it; and foster good relations between people who share a protected characteristic and people who do not share it (EHRC 2020a).

The Act makes it unlawful for a school to discriminate against, harass or victimise a pupil or potential pupil in relation to admissions, or the way it provides education and access to any benefit, facility or service, or by excluding a pupil or subjecting them to detriment. Schools are permitted to treat disabled pupils more favourably than pupils without disabilities and are expected to make ‘reasonable adjustments’ to meet the needs of pupils with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) (Department for Education 2014a). Unlawful behaviour defined by the Act include:

- Direct discrimination: When a person treats one person less favourably than they would another because they have a protected characteristic.

- Indirect discrimination: When a provision, criterion or practice appears neutral, but its impact disadvantages people with a protected characteristic. For example banning all headwear would indirectly discriminate against people who wear headwear for religious reasons.

- Harassment: Unwanted conduct that creates an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment for the complainant, or violates their dignity.

- Victimisation: Treating someone unfavourably because they have taken (or might be taking) action under the Equality Act, or supporting somebody who is doing so. (EqualiTeach 2018, p. 7)

Principles and Complexities of Inclusive Education

The principles underpinning inclusive education have been evolving since the 1980s, with global and national commitments to the movement (see the Salamanca Statement [UNESCO 1994] and the Dakar Framework [UNESCO 2000]). Stemming from the concern relating to the educational provision available to children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND), there has historically been a narrow view of inclusion – as specifically related to special educational needs (SEN). The concept of inclusive education has since widened and is based upon a ‘moral position which values and respects all individuals and which welcomes diversity as a rich learning resource’ (CSIE 2018b). Diversity can be understood as:

All the ways we are unique and different from others. Dimensions of diversity include but are not limited to … ethnicity, religion and spiritual beliefs, cultural orientation, colour, physical appearance, gender, sexual orientation, ability, education, age, ancestry, place of origin, marital status, family status, socio-economic circumstance, profession, language, health status, geographic location, group history, upbringing and life experiences. (Calgary Board of Health 2008 cited in Loreman et al. 2010: 23)

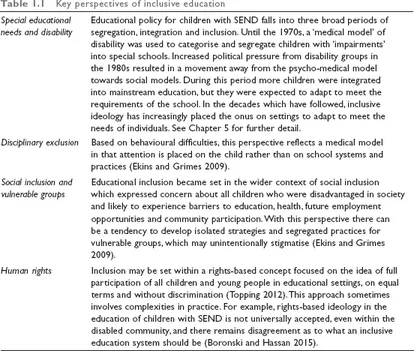

Inclusion is not optional. In the UK there is a legal duty on schools and early years settings to provide social and learning spaces which all pupils can access and where the needs and backgrounds of all children are catered for and valued. The key perspectives of inclusive education which are outlined in Table 1.1 are not exclusive of each other nor are they chronologically sequential. Instead, there is a ‘dynamic relationship between the various perspectives’ and they should be considered as occupying ‘the same ground with different (sometimes competing) emphases and popularity’ (Clough 2006: 9). The ‘Index for Inclusion’ (Booth and Ainscow 2011) provides a useful overview of ideas relating to the philosophy of inclusive education.

Activity Debating inclusive education

Debate the following statements, justifying why you agree or disagree. Try to draw on the experience you have had in practice.

- ‘Inclusive education is easy to achieve.'

- ‘A practitioner can be trained to meet the needs of all pupils.'

- ‘Inclusive education can sometimes be detrimental.'

- ‘A practitioner will realise if they have any biased ideas or discriminatory attitudes about the children and families in their settings.'

Translating inclusion into practice

It has long been acknowledged that inclusion is complex and is at risk of remaining idealistic, as principles contained within policies are not always easily translated into practice (Gibson 2009). It is essential therefore to acknowledge the realities, tensions and dilemmas which may confront practitioners. Similarly, it is important that practitioners recognise that inclusion is an ongoing process which may never be fully achieved due to multifaceted exclusionary factors and newly emerging challenges.

Case study Inclusion in practice

Mr Jones is a teacher at St Mary's Roman Catholic school. A number of the children have diverse and complex family/social backgrounds including: a Traveller boy; a young girl who lives with same-sex foster parents; a child who has refugee status; a young boy who has Down's syndrome; a child who lives in extreme poverty; a boy who is experiencing gender dysphoria; and a highly able child.

Task

Working with a small group of peers, decide whether Mr Jones works within the early years or Key Stage 2 (7–11 years) and consider the following questions.

- Identify two children and discuss how each might be disadvantaged or vulnerable in the setting.

- Discuss the challenges that Mr Jones might face when trying to be inclusive for these children.

- Mr Jones is struggling to address the needs of all of the children and feels he will have to prioritise in terms of his time and the resources available. What advice would you give to him? Do any of the children require priority? If so, on what basis?

- What strategies could Mr Jones put into place to support these children with regard to both their learning and social spaces?

The idea of catering to the needs of all, particularly for children with high levels of diversity and need, can be a daunting task, which is not without its challenges. The adoption of inclusive attitudes and practices will be largely dependent on the personal values of the individual; the quality of continuing professional development available; the level of support offered by senior teachers/managers; and competing pressures for time, funding and resources (Loreman et al. 2010; Topping 2012).

Eradicating prejudice, discrimination and inequality is a difficult task. Practitioners need to be committed and skilled. Positive attitudes are critical to the success of inclusion. It is therefore essential that measures are put into place which call upon practitioners to critically reflect on their own attitudes and practices towards difference and diversity (Department for Children, Schools and Families [DCSF] 2009a; Nutbrown and Clough 2013). Histories, cultures and traditions hold deep-seated stereotypes that should be openly explored and acknowledged in a safe and confidential space (DCSF 2009a).

Intersectionality

It is also important that child practitioners appreciate how elements of identity frequently interact. Intersectionality, a concept introduced by Kimberlé Crenshaw (1989), is useful for understanding the multiple, intersecting aspects of identity (gender, class, economic, race, sexuality, age, language, religion, disability) which can lead to individuals being oppressed and marginalised within society. Routinely used within the field of sociology to examine social inequalities, it is a perspe...