eBook - ePub

Landscapes of Indigenous Performance

Music, Song, and Dance of the Torres Strait and Arnhem Land

Fiona Magowan

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 208 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Landscapes of Indigenous Performance

Music, Song, and Dance of the Torres Strait and Arnhem Land

Fiona Magowan

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

This collection shows how traditional music and dance have responded to colonial control in the past and more recently to other external forces beyond local control. It looks at musical pasts and presents as a continuum of creativity; at contemporary cultural performance as a contested domain; and at cross-cultural issues of recording and teaching music and dance as experienced by Indigenous leaders and educators and non-Indigenous researchers and scholars.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Landscapes of Indigenous Performance als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Landscapes of Indigenous Performance von Fiona Magowan im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Media & Performing Arts & Ethnomusicology. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

1.

From ‘Navajo’ to ‘Taba Naba’

Unravelling the travels and metamorphosis of a popular Torres Strait Islander song

Martin Nakata and Karl Neuenfeldt

Similar to other social ‘things’ (Appadurai 1986), songs have a social life; similar to other symbolic goods they circulate in a global cultural economy (Appadurai 1990). Although globalisation (Robertson 1992) and ‘world music’ (Taylor 1997) are sometimes presented as processes unique to the late twentieth century, there have been many antecedents for extensive global movements of cultural ‘things’ such as music, especially during the eras of extensive European colonial expansion in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Thomas 1991). From the late eighteenth century, Australia has been intimately linked to the circulation of European and North American popular culture forms (MacKenzie 1992; Waterhouse 1990) including music (Whiteoak 1999). This process reached into non-metropolitan, geographically isolated areas of Australia such as the Torres Strait region of far northern Queensland (Neuenfeldt & Mullins 2001).

In this chapter, we explore the genealogy and speculate on the migration and Indigenisation of a well-known and often performed song in the music repertoire and performance culture of contemporary Torres Strait Islanders (henceforth Islanders). The song is now known as ‘Taba Naba’. However, we will argue that the song (in particular its music and also some lyrics) can be traced to a song copyrighted in the USA in 1903 as ‘Navajo’.

A main focus here is how the end product, the song in its current performed and recorded renditions, may be the result of complex processes linked to the historical globalisation of North American and European music genres and their subsequent localisation and Indigenisation in Australia. Although the song’s genealogy and migration is of interest, also of interest is the process of Indigenisation (Stillman 1993). This process arguably reflects the particularities of the colonial history of the Torres Strait and the Islanders’ historical response to appropriate and ‘customise’ outside forms to suit their own cultural purposes (Beckett 1987). The song’s more recent changes and evolution also arguably reflect the recent recognition and incorporation of Islander culture by ‘mainstream’ Australia—its return to the ‘global’ remade as a ‘traditional’ Torres Strait Islander song. For whatever reasons, the song resonates today as part of the soundtrack of Islanders’ identity narrative (Martin 1995).

To paraphrase Thomas’s observation on objects that circulated in colonial-era Oceania (1991: 4), songs are not what they were made to be but what they have become. The original, now deceased composer of the music and the author of the lyrics of ‘Navajo’ might be surprised at how and why the song has become an aural and performance icon of Islanders’ music repertoire and performance culture and by extension that of public culture in contemporary Australia. This process, embedded in the always complex and often contested politics of culture (Bottomley 1992), is especially interesting. The song arose out of the racially stereotyped songwriting and performance conventions of the late nineteenth and early twentieth-century genres of ragtime and Tin Pan Alley (Jasen 1988; Jasen & Jones 2000). Yet through artistic expression it has come to represent a very distinct kind of Australian Indigeneity or ‘blackness’.

Torres Strait background

Due to the Torres Strait region’s strategic location between the Pacific and Indian Oceans and its history as a centre for maritime industries (Mullins 1995), it can be appreciated as a ‘transcultural contact zone’; that is, a social space ‘where different cultures meet, clash and grapple with each other’ (Pratt 1992: 4), often amidst asymmetrical power relations. Music was one of the many cultural artefacts which circulated in the Torres Strait along with its mobile and multicultural population. As one of the more benign and portable kinds of cultural artefacts, music was perhaps more open to transcultural borrowings and adaptations than others, a process noted by Haddon (1889, 1901) and in accounts of local public culture events, as in The Torres Strait Pilot (Anonymous 1903: 1).

Historically, Islanders lived on islands scattered between Australia and New Guinea that varied considerably as to topography, fertility and size. With the establishment in the 1870s of permanent European settlement in the region, the arrival of Christianity, and the migration of workers from Polynesia, Melanesia and Asia for the maritime industries (e.g. bêche-demer and pearling), Islanders were eventually incorporated into the Australian social, economic and political sphere (Singe 1989). They also eventually came under the direct control of the race-based laws regulating the lives of Indigenous Australians (Beckett 1987).

According to 2001 census figures, there are approximately 36,810 Australians who identify as Torres Strait Islanders and 17,630 who identify as both Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2001). The majority of Islanders now live on the mainland of Australia (Taylor & Arthur 1993) but approximately 6,800 still reside in the Torres Strait. They live either on the main administrative centre of Thursday Island or in smaller communities on the Outer Islands or Cape York Peninsula.

Colonialism had a profound effect on Islander society, culture and economy (Beckett 1987) and the relationships between Islanders’ aspirations and those of the ‘mainstream’ dominant Anglo-Australian culture remain problematic, especially in key areas such as education (Nakata 1993), religion (Mullins 2001) and governance (Torres Strait Regional Authority 2001). Descriptions of the Islanders’ cultural space in terms of simple ‘either/or’ relations between the Islander and mainstream domains or traditional and Western domains have been contested in recent times (Nakata 1997a). The ‘transcultural contact zone’ or ‘cultural interface’ (Nakata 1997b) which has historically shaped and continues to shape Islander lives is argued to be a much more complex intersection of contesting and competing discourses where Islanders have been marginalised economically and politically but nevertheless active in asserting and reshaping their cultural and political identities within that space (Beckett 1987; Nakata 1998).

The songs

We suggest the ‘original’ source of ‘Taba Naba’ is the refrain of ‘Navajo’, written by composer Egbert Van Alstyne and lyricist Harry B. Williams, a versatile and successful early nineteenth century songwriting team (Jasen 1988: 49).1 The US publishers Shapiro, Bernstein and Company copyrighted the song in 1903.2

Down on the sandhills of New Mexico / There lives an Indian maid / She’s of the tribe they call Navajo / Face of a copper shade / And every evening there was a coon / Who came his love to plead / There by the silv’ry light of the moon / He’d help her string her beads / And when they were all alone / To her he would softly crone [croon]

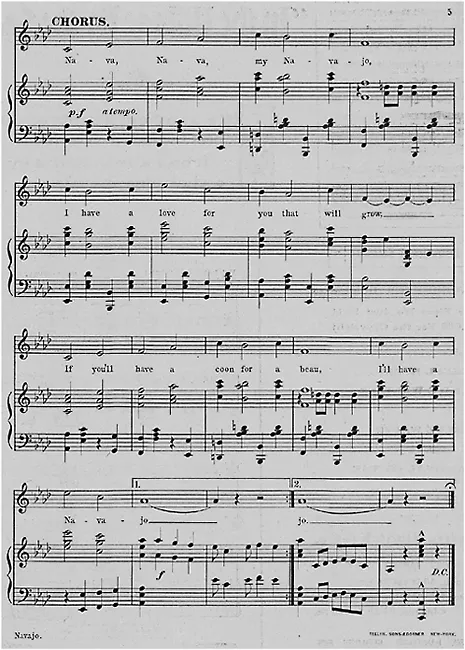

Nava Nava my Navajo \ I have a love for you that will grow / If you’ll have a coon for a beau / I’ll have a Navajo

This Indian maiden told the colored man / She wants lots to wear / Laces and blankets and a powder can / Jewels and pipestone rare / You bring me feathers dear from the store / He answered have no fear / I’ll bring you feathers babe by the score / If there’s a chicken near / With joy then the maiden sighed / When to her once more he cried

Nava Nava my Navajo \ I have a love for you that will grow / If you’ll have a coon for a beau / I’ll have a Navajo

‘Navajo’ by composer Egbert Van Alstyne and lyricist Harry B. Williams. (Copyright 1903, Shapiro, Bernstein & Co.)

‘Navajo’ can be classified as an Indian Intermezzo (also known as ‘Indian Love Songs’ or ‘American Indian Songs’). It was a genre popular in North America in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century (Gracyk 2002) and was circulated via sheet music, cylinder recordings and live performances (Charosh & Fremont 1983). The genre was coterminous with the ‘closing of the frontier’ and more importantly the end of the ‘Indian Wars’ in which Native Americans had vast areas of the North American continent taken from them by conquest, disease and the destruction of previously sustaining natural environments. ‘Playing Indian’ has a long history in US popular culture (Deloria 1998) and the Indian Intermezzo genre can be appreciated as a cogent example of ‘imperialist nostalgia’ (Rosaldo 1989) in which a society romanticises or fetishises, via stereotypes (positive and negative), the very thing or culture it has helped destroy. In this instance the romanticised ‘Noble Savage’ depicted in the sheet music’s artwork belies the grim reality of conquest. In colonial Australia there was an abiding fascination with the Indian Wars of North America in newspaper reports and Wild West Shows within touring US and Australian circuses. The circuses required suitable music for re-creations of ‘Indian’ battles.

What is of particular interest with ‘Navajo’ is how it stereotypes Native Americans and simultaneously stereotypes African–Americans in the style of ‘coon’ songs, which were popular in North America from the 1880s until the 1910s. Coon songs featured ‘comical’ lyrics about African–Americans and were written both by European and African–Americans. Coon songs are described by Jasen and Jones as: ‘racist jokes rhymed and set to music, and there was no more low-brow genre of musical expression’ (2000: xxix), although they were not necessarily perceived thus when they were written. As Whiteoak (2002) notes: ‘These [songs] were ideal for modern dances like the one-step and tended to deal with themes of contemporary US society, eschewing the, by now, anachronistic “coon” vernacular lyrics and stereotyped African–American themes of coon song and earlier minstrel song’...