![]()

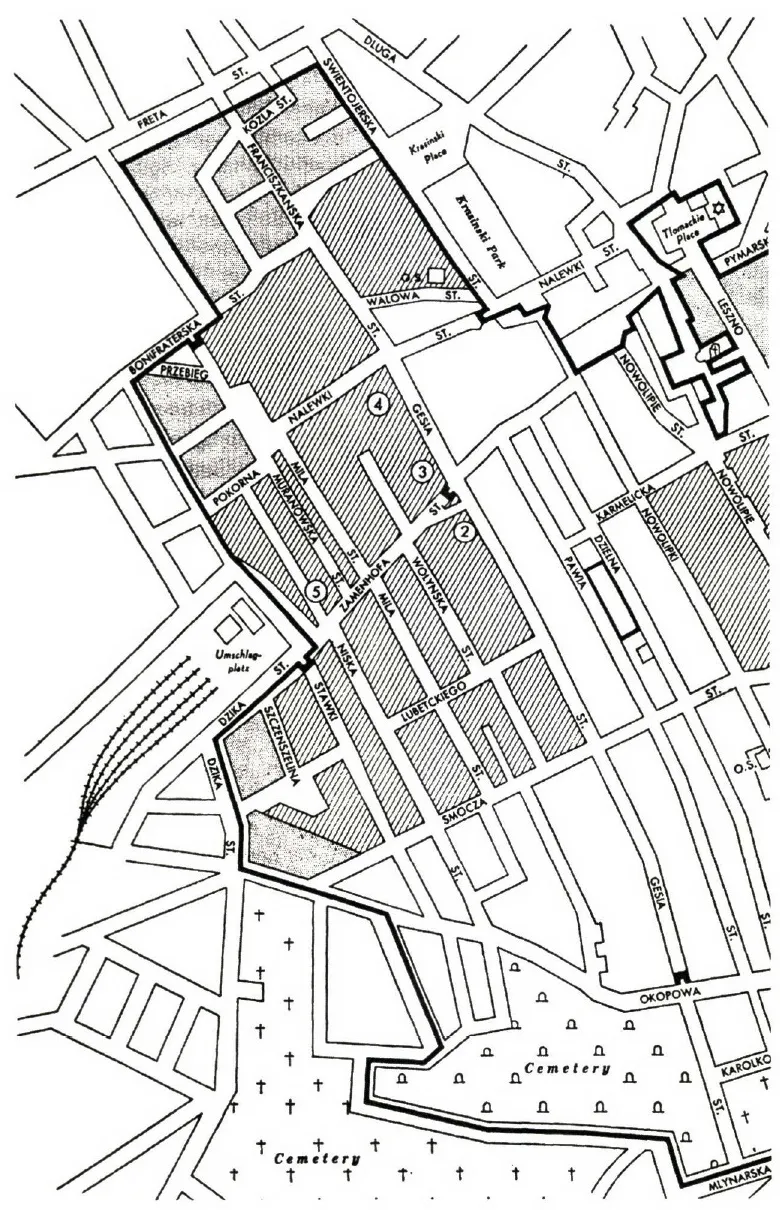

STREET MAP OF THE GHETTO (1)

![]()

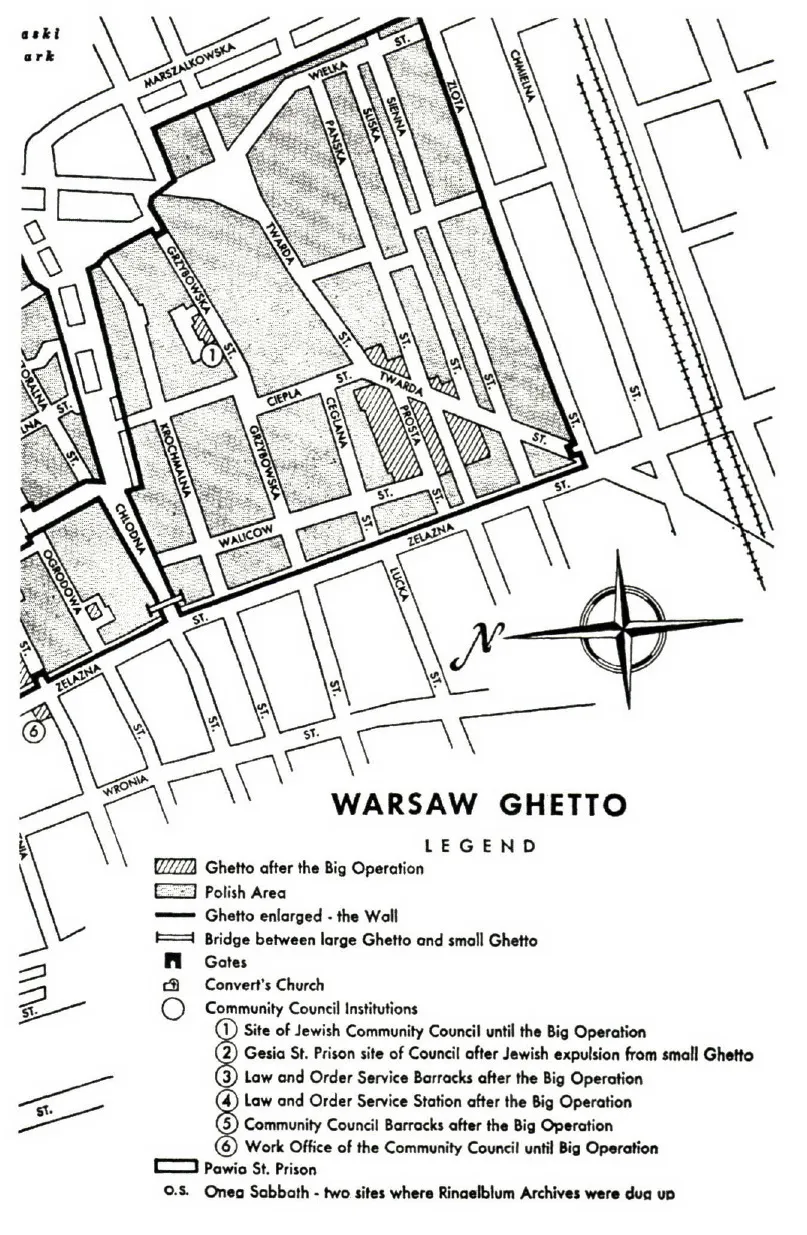

STREET MAP OF THE GHETTO (2)

![]()

MAP OF POLAND

![]()

BEFORE THE GHETTO

EDITORIAL COMMENT

Emmanuel Ringelblum’s Notes from the Warsaw Ghetto begin in January, 1940, three months after the occupation of Warsaw by the German army. In September, 1939, the Germans found some 360,000 Jews living in Warsaw. The Jews had fought desperately with the Polish army against the overwhelming Nazi blitzkrieg; Ringelblum notes several instances of individual bravery. They had formed a special Jewish Committee to aid in the defense of Warsaw during the three-week siege. No one could have anticipated the genocide that was to annihilate the mass of European Jewry during World War II. But the experiences of German Jewry under Nazism had made it quite plain that Polish Jews could expect nothing but evil from a Nazi occupation of their country. It would be some time before Hitler was to try to fulfill his promise to extirpate all of Jewry from the continent of Europe. Soon after the occupation of Warsaw, however, a series of special decrees were directed against Warsaw Jewry. The economic, political, and social ruination of the Jews was intended—with their physical “liquidation” as the inevitable result. The property of the Jews was registered, their bank accounts frozen, their factories and businesses expropriated, making it almost impossible for them to earn a living. The Jewish quarter of Warsaw was termed a quarantine area, and the refugees who poured into Warsaw from the provinces—both Jewish and Christian, either voluntarily, or deported-were forced to live in that area. Jews were further set off from the rest of the city’s population by having to wear a special arm band—a white brassard 10 centimeters wide with a six-pointed Jewish star. They were forced into labor brigades and put on very meager rations.

It was the Nazi practice to force the Jews themselves to administer the discriminatory decrees that produced their suffering. A veteran Jewish community leader, Adam Czerniakow, was called to the Gestapo on October 4, 1939, and ordered to appoint a new Jewish Council to supplant the old, limited Jewish Community Council of Warsaw. (Until modern times, Community Councils had been autonomous self-regulating bodies, accepted by the Jewish communities in Eastern Europe as the local authority in Jewish religious life. But since the emancipation of Polish Jewry and the rise of a secular society, they had lost their original representative function.) The new Jewish Council was to be a government-in-miniature, but without a trace of independence. It was the Councils duty to furnish the work battalion demanded by the Occupying force; to maintain peace and order (through an Ordnungsdienst, or Law and Order Service, consisting of Jewish policemen); to train skilled workers; to attend to sanitation and medical needs—particularly to combat epidemics. For these purposes they could levy taxes (Ringelblum has many harsh words about the inequities of the tax system). Later, after the Ghetto was set up, the Council also organized a workshop where raw materials allotted by the Germans were finished by Ghetto workmen and artisans for the Wehrmacht. The Jewish Council was from the first in an unenviable position. Its members could satisfy neither their despotic Nazi masters, whose demands were impossible, nor the Jewry of Warsaw, who viewed them as a thinly disguised German agency, and, as such, necessarily evil.

It was a year before the Ghetto was set up. In November, 1939, one had been projected, but the Warsaw Jews had succeeded in averting it by paying a huge sum of money. Meanwhile, the “Jewish quarter of Warsaw” was at the mercy of Nazi soldiers, abetted by their Lett and Lithuanian auxiliaries and the riffraff of the city. The notes for this period are full of incidents of individual, casual brutality—the usual random violence of an occupying army, in this case intensified by the conviction of the conquerors that they had at their mercy a species of submen.

There was as yet no organized armed resistance—the situation was still too fluid, too novel, not sufficiently desperate. Warsaw Jewry was in a state of shock after the bombings of their homes, the loss of their livelihoods, the dislocations and stresses of readjustment to living on the edge of catastrophe. Everything was still in a state of emergency; the city teemed with strangers—German soldiers, refugees from the provinces, foreign civilian administrators. Indeed, the whole country was in a state of upheaval. The Germans and Russians had divided Poland between them: Germany taking a large western third for itself to be reincorporated into the Third Reich; Russia annexing an eastern third; and a buffer state, the Government General of Poland, being set up between the two armies, as an “unincorporated territory.” The new Government General lay in the region between the Vistula and Bug rivers, and was ruled by a German Governor General, one Hans Frank, whose seat was in Kraków, not the former capital, Warsaw. Reports of disaster streamed into the city. People held their breath, waiting for the worst to happen.

At the end of April, 1940, the first ghetto was established in Lodz, the foremost industrial city of Poland. Now the picture began to become clearer. The Middle Ages were returning.

![]()

GUIDE TO PRONUNCIATION OF POLISH NAMES

POLISH VOWEL—ENGLISH EQUIVALENT

a—a, as in arm

e—e, as in bed

i—ee, as in bee

o—o, as in honey, or u, as in but

u—oo, as in school

POLISH CONSONANT—ENGLISH EQUIVALENT

c—ts, as in Tsar

j—y, as in young

w—v, as in vice

cz—ch, as in charm

rz—French j, as in jeune, or English garage

sz—sh, as in shape

ch—ch, as in Scottish loch

![]()

1/JANUARY, 1940

Dear Father,{1}

What happened in Wower, outside Warsaw, has been cleared up slightly. It was this way: Some Poles were sitting in a restaurant. Two German policemen came in (one of them a captain of the watch) and began to shout at the Poles. The latter took out revolvers (apparently there was only one) and shot the Germans. Some of the Germans shot were bandits. Nevertheless, They are demanding that the murderers be handed over. Meanwhile, They’ve ordered the body of the restaurant owner to be exhumed and hanged. He is to hang for all to see for seven days.

The consternation of Friday, December 30, was, it is now said, unfounded. Not a single German was killed. Word has it that this time it was thieves work. Still another rumor is that a German soldier got into a fist fight at night on Towarowa Street and was knocked out.

The mortality among the Jews in Warsaw is dreadful. There are fifty to seventy deaths daily. Before the war, the rate used to be ten. The burial tax rate has been fixed at 50 zlotys in Warsaw proper, and 100 zlotys in the suburb of Praga. In Radom the synagogue was burned down, as was the Jewish Council building. The same in Torun, where there were 1,000 people deported from Lodz. In Rajsze there are about 6,000-7,000 refugees from Kalisz, Lodz, Upper Silesia. The lords and masters{2} not too bad. If you grease the right palms, you can get along. In Torun, Polish soldiers were shot, the Jews ordered to bury them. No Jews are taken on any jobs. Two Jews were standing on..., two lords and masters sprang out of a passing auto, dragged one of the Jews into the car, shouting, “You bandit!” What happened to the Jew unknown. Tonight Dr. Cooperman was shot for being out after eight o’clock. He had a pass. A Jewish worker who belonged to the labor battalion was killed in Praga.

The public announcement page in the Lodz News looks like a graveyard. Full of notices put in by the ethnic German trustees of Jewish firms calling on the firms’ debtors to report the debts to the new trustees.

Many of the deportees die afterward as a result of the terrible experience. An elderly woman from Posen, who had walked 70 kilometers from Lewartow to Ostrow, died in Warsaw. The Jewish shopkeepers no longer keep their cash in drawers, in the usual way, but conceal it somewhere in the building—in chests, vessels, glasses, pots, or the like.

A sign on the main registry office at 26 Dluga Street: Eintritt Für Deutsche Soldaten Verboten [Out of Bounds for German Soldiers]. Because of the great dread of epidemics. A whole row of streets—Sliska, Rivna, and others—sealed off with barbed wire. Today saw a house on Grzybowska Street that is under quarantine. Two hospitals for communicable diseases have been quarantined; the doctors and nurses can’t leave. The Jewish Council of Warsaw ran a collection of sheets and pillows for the hospitals. There are cases of packages having been left outside an apartment when the porter found out there was (supposedly) typhus in that household.

From sometime in October until about six weeks ago, the Swedish consulate accepted messages for transmittal to America. Lately, many people have received questionnaires from America asking how they were; you could send a personal reply of up to twenty-five words. Communicating with one’s relatives abroad is enormously important. There are thousands on thousands of families here that used to be suppor...