![]()

CHAPTER ONE

I WASN’T TEN MINUTES inside the door of the Royal Hotel at Galway before I was accosted on the stairs by a complete stranger, a young man of about thirty years of age.

‘Come down till I treat you,’ he said. As I turned to go with him he added: ‘My name is Jimmy Dillon. What’s yours?’ I told him. ‘I’ll call you Bob,’ he said.

We went down the stairs and into the bar. There were only two men there. One was small and wizened. He was wearing corduroy breeches and leggings, and was sitting before the fire, reading a newspaper. He took little notice of our entry. The other was heavily built and florid. He wore a mustard-coloured tweed suit, and overlapped a high stool beside the marble counter. His elbows rested on the counter and his chin was sunk in his fists. His lower lip was thrust far forward. He seemed to be weighed down with some great mental problem.

‘You’re someone,’ he said, with emphasis, pointing his finger at me, as Jimmy and I came in. ‘I seen you before. I seen you at the station. You didn’t see me. Your back was facing me. “That’s a man,” I said to Paddy Lydon, “that’s a man,” I said. My name is Laffin, Tim Laffin.’ He swung round on his stool. The sunburnt dome of his bald head seemed to rise higher and higher above his ears. ‘Now,’ he said with great solemnity, ‘I’m a plain man, a very plain man. I’m a man of few words. Tell me, in one sentence, in one sentence only, what’s wrong with the world?’

It would not be the easiest question to answer in one sentence at any time, still less on the spur of the moment that one arrives in Galway. ‘I suppose,’ I ventured, ‘the only hope is in a revival of real religion.’

‘Isn’t the Pope looking after that?’ said the man at the fire.

‘Shut up,’ said the man of few words.

But I was punctured. Any great thoughts that I might have uttered were lost to the world.

Laffin began to speak again, but Jimmy interrupted him. Cattle were fetching five pounds more a head in England than in Ireland, he said.

‘You’d get five pounds more for that glass of stout if you had it in hell,’ said the man by the fire.

‘You go to hell,’ said Laffin.

‘And send you my ashes as snuff. Wouldn’t I laugh to see you sneezing!’

‘Once that man’s hat is on his head his house is thatched,’ whispered Jimmy to me, pointing to the little man. ‘He’s a tangler. He hasn’t the price of one beast in the world. But he’s a good judge. He’ll buy early, knowing he can sell at a profit before the day is out. He can’t pay till he sells.’

The little man got up and left us.

‘And he puts that many airs on him, looking down his nose at every one,’ added Jimmy a little louder, as the door closed.

‘Them as looks down their nose don’t see far beyond it,’ said Laffin.

‘And he’s never in the same place two days—walks, walks, walks,’ said Jimmy.

‘Might as well tell a swallow not to travel,’ said Laffin.

‘Every man to his trade,’ said Jimmy.

‘There’s a deal of difference between selling bad eggs and cooking them,’ said Laffin. ‘Now will ye all stop talking and listen to me for one moment!’ he continued. ‘One would think the lot of ye had been vaccinated with gramophone needles. Listen to me, now!’

But nobody would listen. The arrival of a party of drovers gave me an opportunity to slip away. Jimmy came after me. ‘Will you come to the fair in the morning?’ he asked. ‘I’ll call you at four o’clock.’

It was already getting dusk that evening as I wandered into the town. From the corners of narrow streets one caught glimpses of archways, and colour-washed walls lit by hidden lamps. There was no noise of traffic, except footsteps on the pavement. Groups of men stood at the corners of the streets, dark silhouettes of women in shawls passed by. One old woman coming round a corner nearly bumped into me. I stepped aside to let her pass. ‘Wisha, God bless you,’ she said as she went by.

Down by the Claddagh, the oldest fishing village in Ireland, I stopped to look over the bridge.

‘You’re a stranger here?’ a man said to me.

‘I am,’ I answered.

‘This is the Claddagh bridge,’ he said, ‘and the one above which you can’t see in the dark is O’Brien’s bridge, and the one above that is where you’ll see the salmon waiting to go over the weir, hundreds of them, thick as paving stones; and in the summer as many visitors polishing the parapet with their elbows, and gaping at the fish below who don’t give a damn for any of them.’

‘D’you ever pick one out?’ I asked.

‘It’s preserved,’ he said.

‘Even so?’ I queried.

‘Maybe,’ he said with a smile.

After a pause while we watched the torrent of brown flood water glinting in the light of the street lamps he spoke again. ‘There’s the Spanish Arches behind you, but you can’t see them, and the Spanish Parade is alongside of them. That’s where you’d see the Spanish grandees in their cocked hats walking out of a Sunday. How many hundred years ago? I suppose it would be near five hundred. Galway was a mighty fine place then.’

Again we watched the river sluicing down from Lough Corrib.

‘Have you been to the old jail,’ he asked, ‘with the skull and the bones in stone over the door? Wasn’t it the divil’s own thing for the judge to do, to condemn and hang his own son?’

‘But hadn’t he committed a murder?’

‘Yerra, murders were cheap enough in them days. Sure, the whole world was murdering each other, same as they’re doing now indeed.’

‘I believe,’ I said, ‘there are some who think that Judge Lynch never did hang his son; that it’s all a story.’

‘That he never hanged his son? Isn’t it written up on the wall with the year it happened, 1493, and all? And doesn’t the whole world know what lynch law means, and how could it have spread the world if he never done it? I suppose they’ll say that Columbus never said mass in St. Nicholas beyond, before he went to America, and that he didn’t take a Galway man with him, Rice de Culvey was his name. Faith, they’ll say next that Columbus never discovered America at all.’

I thought it better not to hint that some thought America had been visited by the Portuguese at least fifty years earlier, and that there were Norse colonies in Greenland in the eleventh century.

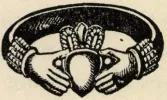

‘Come down with me now and I’ll show you the Claddagh,’ he said. ‘Well, you can’t see it; but we’ll walk through it. ‘Tis as well for you that you can’t see it, for what is it now but slates and stones, and all the houses in straight lines. Planning, they calls that. There was a time when there were eight thousand in the Claddagh and they all fine healthy fishermen, and now there isn’t five hundred. I tell you, the vests they wore in them days would make coats for men today. And they had their own king and queen, and not one of them would marry outside of the Claddagh, and they had their own wedding ring, the Claddagh ring, with the two hands catching hold of the crowned heart. And the houses were thatched, and warm in winter and cool in summer, and they didn’t know what disease was, for no man died but by the will of God. And today, what with the damp out of the concrete floor under their feet, and the cold out of the slates over their heads, ‘tis only one sneeze they need give and they drop dead.’

By this time we had reached the long pier that stretches out to the west of Galway Harbour. The moon was rising over the town, and the spire of the fourteenth-century church of St. Nicholas was silhouetted against the sky. Along the quays great, gaunt warehouses, with empty windows, told of former prosperity. Sea-gulls were crying out at sea. A man in a boat was singing Galway Bay.

‘To see again the moonlight over Claddagh

And to watch the sun go down on Galway Bay.’

‘I’ll see you back,’ said my companion. We turned and walked through the narrow streets together. I could hear the notes of a harp from another street. At the hotel I invited him in.

‘Oh, no!’ he said, ‘I never touch a drop.’ Then as he was going: ‘I’ll leave some photos for you in the morning, and I’ll see if I can find a ring.’

These Claddagh rings, of which my guide had spoken, have been for many generations the wedding token of the peasantry in the district stretching from the Aran Isles in the west through southern Connemara to some ten or twelve miles east of Galway....