Magic

Jamie Sutcliffe

- 240 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

Magic

Jamie Sutcliffe

Über dieses Buch

From the hexing of presidents to a renewed interest in herbalism and atavistic forms of self-care, magic has furnished the contemporary imagination with mysterious and complex bodies of arcane thought and practice. This volume brings together writings by artists, magicians, historians, and theorists that illuminate the vibrant correspondences animating contemporary arts varied encounters with magical culture, inspiring a reconsideration of the relationship between the symbolic and the pragmatic. Dispensing with simple narratives of re-enchantment, Magic illustrates the intricate ways in which we have to some extent always been captivated by the allure of the numinous. It demonstrates how magical cultures tendencies toward secrecy, occlusion, and encryption might provide contemporary artists with strategies of remedial communality, a renewed faith in the invocational power of personal testimony, and a poetics of practice that could boldly question our political circumstances, from the crisis of climate collapse to the strictures of socially sanctioned techniques of medical and psychiatric care. Tracing its various emergences through the shadows of modernity, the circuitries of ritual media, and declarations of psychic self-defence, Magic deciphers the evolution of a magical-critical thinking that productively complicates, contradicts and expands the boundaries of our increasingly weird present. Artists surveyed:

Holly Pester, Katrina Palmer, Ithell Colquhoun, Anna Zett, Monica Sjöo, Sofia Al-Maria, Jack Burnham, Jeremy Millar, Susan Hiller, Mike Kelley, Morehshin Allahyari, Center for Tactical Magic, David Steans, Porpentine, Travis Jeppesen, Linda Stupart, Caspar Heinemann, Elizabeth Mputu, Faith Wilding, David Hammons, Ana Mendieta, Henri Michaux, Kenneth Anger, Benedict Drew, Mark Leckey, Robert Morris, Jenna Sutela, Haroon Mirza, Zadie Xa, Saya Woolfalk, Ian Cheng, Tabita Rezaire, Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth, Elijah Burgher, Pierre Paulo Pasolini, Sahej Rahal Writers:

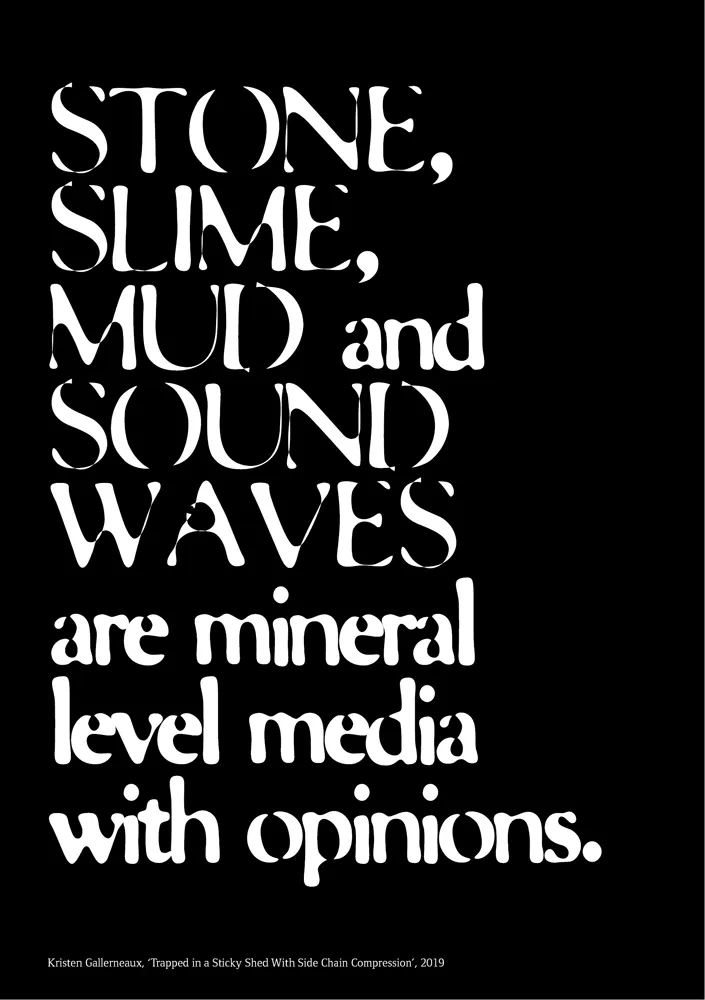

Charles Fort, Victoria Nelson, Gary Lachman, Yvonne P. Chireau, Randall Styers, Isabelle Stengers, Alan Moore, Simon O Sullivan, Lucy Lippard, Louis Chude Sokei, Patricia MacCormack, Mark Pilkington, Æ, Annie Besant & C.W. Leadbeater, Michel Leiris, Aimé Césaire, Austin Osman Spare, Erik Davis, Mark Dery, Elaine Graham, Jeffrey Sconce, Giulia Smith, Esther Leslie, Alice Bucknell, Gary Zhexi Zhang, Hannah Gregory, Kristen Gallerneaux, Mahan Moalemi, Jamie Sutcliffe, Gregory Sholette, Aaron Gach, Eugene Thacker, Diane Di Prima, Allan Doyle, Aria Dean, Emily LaBarge, Lou Cornum, Joy KMT, Scott Wark, McKenzie Wark, Phil Hine, Jackie Wang, Sean Bonney

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Information

Techgnosis: Magic, Memory and the Angels of Information//1994

One of the most compelling snares is the use of the term metaphor to describe a correspondence between what the users see on the screen and how they should think about what they are manipulating […]. There are clear connotations to the stage, theatrics, magic – all of which give much stronger hints as to the direction to be followed. For example, the screen as ‘paper to be marked on’ is a metaphor that suggests pencils, brushes, and typewriting […]. Should we transfer the paper metaphor so perfectly that the screen is as hard as paper to erase and change? Clearly not. If it is to be like magical paper, then it is the magical part that is all important […].–Alan Kay, ‘User Interface: A Personal View’

While allegory employs ‘machinery’, it is not an engineer's type of machinery at all. It does not use up real fuels, does not transform such fuels into real energy. Instead, it is a fantasized energy, like the fantasized power conferred on the shaman by his belief in daemons.–Angus Fletcher, Allegory

Within the armor is the butterfly and within the butterfly – is the signal from another star.–Philip K. Dick