eBook - ePub

Nostalgic Design

Rhetoric, Memory, and Democratizing Technology

William C. Kurlinkus

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Nostalgic Design

Rhetoric, Memory, and Democratizing Technology

William C. Kurlinkus

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Nostalgic Design presents a rhetorical analysis of twenty-first century nostalgia and a method for designers to create more inclusive technologies. Nostalgia is a form of resistant commemoration that can tell designers what users value about past designs, why they might feel excluded from the present, and what they wish to recover in the future. By examining the nostalgic hacks of several contemporary technical cultures, from female software programmers who knit on the job to anti-vaccination parents, Kurlinkus argues that innovation without tradition will always lead to technical alienation, whereas carefully examining and layering conflicting nostalgic traditions can lead to technological revolution.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Nostalgic Design als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Nostalgic Design von William C. Kurlinkus im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Sprachen & Linguistik & Sprachwissenschaft. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Thema

SprachwissenschaftI

Identifying Nostalgic Conflicts

Chapter 1

Nostalgic Design

Between Innovation and Tradition

Nostalgia, in my view, is not always retrospective; it can be prospective as well. The fantasies of the past, determined by the needs of the present, have a direct impact on the realities of the future.

Svetlana Boym, “Nostalgia and Its Discontents”

Do not seek the old in the new, but find something new in the old.

Siegfried Zielinski, Deep Time of the Media

Revolution. noun rev·o·lu·tion \ˌre-və-ˈlü-shən\

1. A radical change in society

2. The regular cycle of an object through its orbit back to a point of origin

Archiving the Moment

“Will, we care about you and the memories you share here,” Facebook greets me when I log in. “We thought you’d like to look back on this post from 10 years ago.” In 2015 the social network introduced On This Day, a feature that encourages users to publicly remember pictures and posts from years earlier. “Never miss a memory,” the site warns; “Here’s a way to rediscover things you shared or were tagged in.” Like many social networking sites, my Facebook account is a technology of memory. It propels a nostalgia boom by inspiring users to revisit archived experiences that might otherwise be lost to the past, but it also persuades users to be nostalgic for the present, to see posts written about the here and now as “memories you share here.” That scenic waterfall you’re hiking past? It’s a potential memory—take a picture before it evaporates. In doing so, Facebook fosters an affective culture driven by what social psychologist Constantine Sedikides calls “anticipatory nostalgia.” Under this logic, citizens view the present as an event to be chronicled in hopes it will become a cherished memory and out of fear that without record that chance for meaning will vanish. Instagram’s retro photo filters similarly trade in this addictive anticipation by vignetting, scratching, overexposing, and, thereby, digitally aging pictures taken just seconds ago. Digital weathering lends a sense of authenticity to memories of now. By housing these archives, technologies of memory acquire a patina of meaning by association, a reification of memorial labor that would be lost if you desert the sites. That is, if you quit, you don’t care about all the people and experiences you’ve shared. But, despite popular sentiment that nostalgia is a fearful response to the new and that social networks manipulate mindless users, it would be careless to label social media users uncritical simply because they enjoy remembering. Because of the archives’ publicly intimate nature—compared to private records like photo albums or home videos—we mindfully collage memories to curate an identity for the world. This account is my best me, a golden-age self I long to return to. I use it to remember a world into being. In this way, nostalgia nurtures active, personal, memorable, and, thereby, meaningful designs.

Alienation through Innovation

Google announced its Fiber initiative in 2012 with ambitions of spreading high-speed internet across the United States. For a low start-up fee, neighborhoods are connected to an ultrafast network. Early on, only “Fiberhoods” that voted for the service could join. And if enough residents in a community preregistered, Google would make the investment, even offering free access to local schools. This campaign held the potential to wire low-income neighborhoods; internet access would be freed of income restriction. Paradoxically, Google Fiber intensified digital inequity. In Kansas City, for instance, just two days before the registration deadline, neighborhoods that preregistered and those that didn’t split directly down Troost Avenue, a street that divides the city socioeconomically and racially. As Aaron Deacon, managing director of the Kansas City Digital Divide Drive, remarks, citizens who didn’t vote for Fiber “focus on feeding people, finding jobs, those end-state social services. There’s a little bit of a gap still in people understanding how using technology tools can achieve those end goals” (Velázquez). Perpetuating the recruitment gap, when Fiber was launched there were no Spanish-language marketing materials available for the city’s sizeable Hispanic population. In failing to teach low-income Kansas City citizens how the service would benefit them, Google’s pro-innovation bias asked users to replace their current concerns and culture with Google’s. In this light, initially at least, Google failed to see that innovation without tradition leads to alienation. Google Fiber needed to become a nostalgic design. Though they eventually spoke with low-income users in town hall meetings, they still wanted consumers, not collaborators. After all, neighborhoods were transformed into Fiberhoods, not the reverse. Instead, Google might have considered: What are this community’s technological memories, traditions, and ambitions? And how can we redesign to achieve these ideals? The goal of such nostalgic localization is the creation of technologies that are simultaneously past and future oriented and, thereby, welcome neglected citizens as their first adopters rather than just the young and rich. What if Google Fiber had originally been designed with the traditions of lower-income black and Latinx citizens in mind, speculating how it fit into their cherished pasts, current realities, and ideal futures? Such overlooked users should not have to wait for new technologies to trickle down to them only to discover they were designed for someone else.1 In this way, nostalgic design affords designers a chance to think outside of Silicon Valley traditions for off-modern values, resources, and timelines that reside just outside of mainstream progress narratives but that might make the future more fully human.

Resistant Remembering

Donna, a thirty-something roller derby skater, directs a group of high-tech digital labs at a major midwestern university. Because she was formerly a software programmer, when you pass her office now, you might think you hear the soft click of coding on a keyboard. But when you enter, rather than seeing Donna programming a web of variables and constants, you see a knitter, eyes on her monitor, while her needles weave a binary of knits and purls. From homebrewed beer to DIY house kits, Donna is a member of a generation that nostalgically turned to craft in the face of digital intangibility and ephemerality. When I ask why she thinks this trend is occurring, she theorizes, “There came a certain point where most people’s jobs are about going somewhere and sitting at a desk all day. . . . [Y]our product is pixels. . . . And I kind of felt like there were people who were frustrated with that ‘I came home at the end of this eight hours, and I don’t have anything to show for it.’ And so, knitting was a way of, like, I’m still doing something with my time, but at the end of that time there’s a physical object here I can show you.” Donna’s job was marked by a loss of physical end products to her labor. In response, her knitting is a process of nostalgic design, a tactical drawing upon a past of feminine making—even if it isn’t her own lived past—to resist cutting-edge alienation and reshape a frustrating workplace. By knitting at her high-tech job, Donna claims a nostalgic right to meaningful labor. We look back to the past when we don’t feel at home in the present. But in looking back, like Donna, we’re always creating futures we’re a part of. Nostalgia resists, slows, and reshapes the world.

It’s no surprise that when designers consider nostalgia—pride and longing for lost or threatened personally or culturally experienced pasts—their minds rarely leap to innovation. Whether to increase profit, skirt irrational traditions, or bolster change, philosophers of technology and design have dismissed nostalgics as narcissistically mired in idealized and artificial memories, halting progress through a “random cannibalization of all styles of the past” (Jameson, Postmodernism 18). In the pages of Print magazine, for instance, typographer Angela Riechers rejects the “misuse of the powers of graphic design” in the nostalgic interface of Churchkey Pilsner, a beer that has to be cracked with a retro churchkey can opener instead of the contemporary pop top. “Nostalgia supplies the rapture of the familiar,” Riechers cautions, “rather than encouraging a venture into uncertain new design territory.” Music critic Simon Reynolds similarly warns that nostalgia halts musical evolution: “[T]he place that The Future once occupied in the imagination of young music-makers has been displaced by The Past: that’s where the romance lies, with the idea of things that have been lost” (“Total Recall”). Theorist of user-centered innovation Eric von Hippel argues that tech firms can learn from the hacks of the first 2.5 percent (Rogers) of technology adopters—“lead users” or “innovators”—ignoring the resistances of the last 16 percent of adopters, unceremoniously dubbed “laggards.” More bluntly, a 2013 ad for the Cree LED light bulb rebukes, “The light bulbs in your house were invented by Thomas Edison in 1879. Now think about that with your 2013 brain. Do you still do the wash down by the crick while your eldest son keeps lookout for wolves? No. You don’t. This is a Cree LED bulb. It lasts 25 times longer. Nostalgia is dumb” (“Cree”). At best, then, nostalgia seems to be the melancholy of the technologically illiterate, a flaw in reasoning to overcome as one learns and grows. How could it ever promote revolutionary futures?

This book investigates just that.

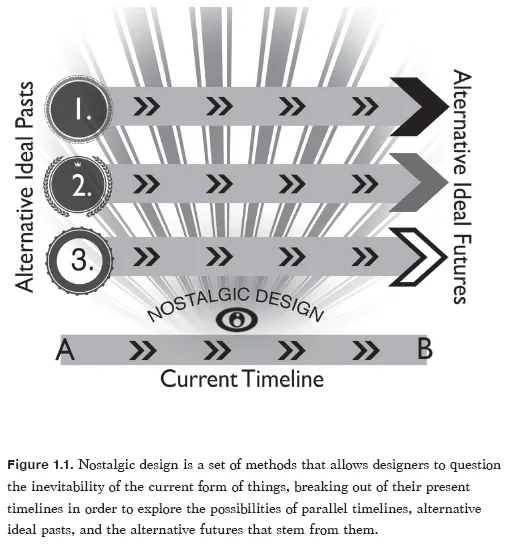

Nostalgic Design argues for using nostalgia to design more democratic, inclusive, innovative, meaningful, and human technologies. It starts from the fact that, psychologically, nostalgia is a homeostatic emotion that arises when people feel left out of the current structure of things. From survivalists who live “off the grid” in the face of new surveillance tech to refugees who turn the smallest pieces of home (a bit of cloth, a cheese grater) into heirlooms that anchor their family in time,2 as social psychologists Clay Routledge et al. observe, “nostalgia is incited by psychological threat and serves to bolster or to restore well-being” (809). Building from this observation, this book illustrates how nostalgia can tell designers what different communities of users love about the past, miss in the present, and wish to recover in the future. What if Facebook purposefully fostered conversations between members of dissimilar traditions through On This Day? What if Google Fiber originally had been designed with lower-class black and Latinx values in mind? What if Donna’s high-tech workplace was redesigned around traditions of feminine making? Parallel pasts and futures surround designers every day (figure 1.1).

Nostalgic Design offers a set of tools that helps designers reach the innovative potential of these alternative timelines. To illustrate this process, I survey the nostalgias of several U.S. technology cultures, from software programmers who knit on the job to repair activists who long to return to a time when consumers could fix a broken device themselves. Through rhetorical analyses and personal interviews, I ask each of these groups, What are you nostalgic for, why, and to which ends? Ultimately, we’ll see that design has a nostalgic heart. That is, despite misconceptions that technology is principally future oriented, all citizens imagine good futures from what they esteem about good pasts.3 When designers address memory and tradition, inclusive designs thrive; when nostalgic ideals are ignored, users are excluded and designs sputter out. Thus, my theses: innovation without tradition leads to alienation and, conversely, the dialogue of conflicting nostalgias leads to revolution through revolution. Designers make a technology good by digging into the humanity of its users—nostalgia is the perfect spade for this archaeology.

Certainly, despite a dismissal of nostalgia by advocates for technological progress, it’s been pretty evident to philosophers of memory and history (Halbwachs; Nora; Assmann and Assmann) that different communities inescapably ground themselves in different collective pasts, and sometimes these ideal pasts collide. Still, few memory theorists have studied how the origin of technological inequity is so often this conflict of traditions, unheard clashes of class, race, gender, sex, age, and ability that make access to technology more difficult for some than for others. Designers Carl DiSalvo et al. label this politics “the rhetoric of design”:4 “[T]he ways in which the built environment reflects and tries to influence values and behavior and . . . the capacity of people to design artifacts or systems that promote or thwart certain perspectives and agendas” (49).

Observe, for instance, as digital media theorists Cynthia and Richard Selfe do, how the design of the computer desktop is based on a nostalgic remediation of business values (manila folders, files, desk calendars) that subtly exclude users who lack a U.S. clerical mindset. “[G]iven that these technologies have grown out of the predominately male, white, middle-class, professional cultures[,]” Selfe and Selfe write, “the virtual reality of computer interfaces represents, in part and to a visible degree, a tendency to value monoculturalism, capitalism, and phallologic thinking” (69). User localization expert Huatong Sun recounts her experience with such cultural restrictions: “But what was a file folder, why did she need to organize her files? She had no idea. As someone who was unfamiliar with American office culture, she had never used a file folder . . . Chinese culture was not as obsessed with paper trails” (3). In the design of the desktop, as in all designs, one tradition is normalized, making thinking about computing in other inventive ways difficult. But consider the possibilities revealed by reimagining the desktop through the traditions of a carpenter’s workbench, a surgeon’s operating table, or a chef’s cutting board. Nostalgic design welcomes new old ways of viewing the world—neostalgic redesign. In doing so, it smashes technological determinism, the belief that “technical progress follows a unilinear course, a fixed track, from less to more advanced configurations” (Feenberg, Between 8).

In exploring both nostalgia (longing for a lost past) and neostalgia (longing for futures that could have been), this book also argues that the best way to recognize diverse traditions and futures in an era where power is decided by technical enterprise is through design methods that employ agonistic democracy (Mouffe)—forms of deliberative making in which stakeholders from divergent traditions design together as collaborators instead of enemies (DiSalvo, Adversarial Design; Björgvinsson et al.). Unfortunately, as the desktop and Google Fiber examples illustrate, technological design is usually left to engineers and scientists who haven’t listened for the clash of user values that makes democracy churn. Such ignorance leads to a technocracy in which a select few voices decide how we live. Furthermore, even when the democratization of technology is theorized, many models don’t provide a practical means to mediate the conflict agonistic democracy thrives on. That is, how does one plan a new park when the city council wants one thing, citizens want something else, and local business owners don’t want a park at all? Designers might agree with a democratic ethic in theory but struggle to mediate between stakeholders in practice. Geoff Mulgan, CEO of the UK’s National Endowment of Science, Technology, and the Arts, critiques designers for this failure to match “their skills in creativity with skills in implementation. . . . [L]ack of attention to organisational issues and cultures . . . condemns too many ideas to staying on the drawing board” (4).

In response, this book explores nostalgia as a pragmatic tool for designers—whether industrial engineers, graphic artists, UX architects, technical writers, physicians, or teachers—to innovate, mediate, and meditate within a global culture of making that is rapidly undergoing a democratization of expertise (Hartelius; Nichols; Gee et al.; Collins). “For a century, designers have seen themselves and have been seen as the sole incumbents and managers in the design field,” writes Ezio Manzini. “Today they find themselves in a world where everybody designs” (Design When 1–2). Expertly trained makers can no longer create in isolation from their users. Citizens want to participate. DIY, maker culture, citizen science—nostalgic self-education on topics from home construction to medicine is at an all-time high in part because citizens feel alienated from, don’t understand, and/or don’t trust the science and technology they use daily. For others, doing it themselves is just plain fun. Thus, if “design” might be broadly defined as the methods by which expert makers create some technology to be operated by a specific user, in a specific context, in order to “change existing situations into preferred ones” (Fuad-Luke, Design Activism 1–5), then good design increasingly welcomes the diverse expertise of all citizens affected by it. That is, good design lies somewhere between outsider innovation and insider tradition. In city planning, for example, this democratization of expertise is seen in participatory charrettes, where residents are welcomed to the table (in town halls, etc.) in order to fit a new building into their preexisting neighborhood. In medicine, it surfaces in patient-centered care when, as a woman is dying from cancer, the physician considers her ideal notion of life, health, and death rather than doggedly chasing the most aggressive treatment (Hutchinson; Nuland; Charon). In this new order, where user participation is not just an ethical choice but an obligation, nostalgia urges empathy by revealing and negotiating the backstories of stakeholder desire (Zhou et al.). What are you nostalgic for, why, and to which ends?

Ultimately, then, nostalgic design is a three-step process of democratic creation by which designers use nostalgia to identify inequities and assets for critical redesign, mediate between conflicting ideal pasts and futures, and design more meaningful technologies. As a scholar and practicing consultant of rhetoric, technical communication, and design research, I specifically seek the new modes of communication, collaboration, education, expertise, and production designers develop to succeed in this age. To begin my search, this introductory chapter examines the historical path of nostalgia from passive illness to critical lens. I then use this lens to provide a glimpse of three nostalgic interactions that can change the way technology affects the world and that, thereby, structure the chapters of this book:

1. Identifying Exclusionary Designs: Nostalgic design is a way to listen for users who feel left out of current conceptions of science and technology and harness these users’ divergent perspectives to create innovative futures through inclusion. (Chapter 2)

2. Mediating Technological Conflicts: Nostalgic design is a platform for designers to mediate between conflicting stakeholders and decentralize their own expertise by uncovering shared logics, encouraging empathy, and concurrently critiquing the present while maintaining hope for the future. (Chapters 3, 4, and 5)

3. Designing Meaningful Products: Nostalgic design is a way to localize designs a...

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Zitierstile für Nostalgic Design

APA 6 Citation

Kurlinkus, W. (2018). Nostalgic Design ([edition unavailable]). University of Pittsburgh Press. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/3061597/nostalgic-design-rhetoric-memory-and-democratizing-technology-pdf (Original work published 2018)

Chicago Citation

Kurlinkus, William. (2018) 2018. Nostalgic Design. [Edition unavailable]. University of Pittsburgh Press. https://www.perlego.com/book/3061597/nostalgic-design-rhetoric-memory-and-democratizing-technology-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Kurlinkus, W. (2018) Nostalgic Design. [edition unavailable]. University of Pittsburgh Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3061597/nostalgic-design-rhetoric-memory-and-democratizing-technology-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Kurlinkus, William. Nostalgic Design. [edition unavailable]. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2018. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.