![]()

Investment 1: Wells Fargo

![]()

![]()

At the heart of this story is fear; a dread of what is in the black box of a bank. Most of the time Mr Market is gloriously insouciant about what banks are doing with all those billions of dollars deposited by millions of families just so long as the bank reports rising quarterly earnings. He knows some of the money is lent out to people to buy houses and some goes to small businesses in the neighbourhood, but as for the rest of it, and how much risk is taken on, Mr Market is blissfully unaware.

Mr Market’s logic is that if the big machine called a bank is producing good dividends, then the managers must have a firm grasp of risk, with sound diversification, thoroughly thought through lending decisions and stacks of collateral backing every loan. Certainly, the bank bosses always sound confident and competent, so that comforts him.

But then recession strikes. The market value of assets used as collateral plunge; indebted companies find orders drying up and they are no longer generating enough cash to meet their loan obligations. Mr Market is now scared. And when Mr Market is scared, he sells those nasty risky things called bank shares. And he can do it indiscriminately.

When recession lights up the corners of some black boxes the whole world can see the horror show. The managers have been lending to people who were on the edge even in the good times. Now that recession and redundancies are here, hundreds of thousands cannot service their mortgages. Bank underwriters were so desperate to lend to the ‘companies of tomorrow’ that they went easy on loan covenants, often not requiring sound collateral at all, or a trading history, or even proven cash-flow generation.

Oh, and then there is lending by way of purchasing financial instruments in the market, whether that be commercial paper, leveraged loans, high-yield bonds or some whizz-bang innovation in the derivative markets. Who knows what their true worth is – in recessions it’s often zero.

Having looked into the dark recesses of some black boxes and been shocked to the core, Mr Market starts to fear that every bank is the same. An entire sector is sold off, share prices collapse.

In this moment of panic, in steps the true investor. That is, those people who ignore Mr Market’s emotions and coolly assess the facts of each company. There will be no tarring with the same brush here.

Each company examined by a value investor is to be treated as though it was his/her own family business and thought is directed towards assessing its long-term viability, its potential to generate cash for shareholders decades into the future.

For that assessment, the value investor needs to make a judgement on the strategic position of the firm – does it have competitive advantages permitting high rates of return on capital employed?

Judgement is also required about the qualities of its managers – are they both competent and shareholder oriented?

And reassurance is needed about the bank’s operational and financial stability both in the short and the long run – sure, it might have some temporary difficulties, but is there a reasonable prospect of lowering potential for financial distress in the medium term?

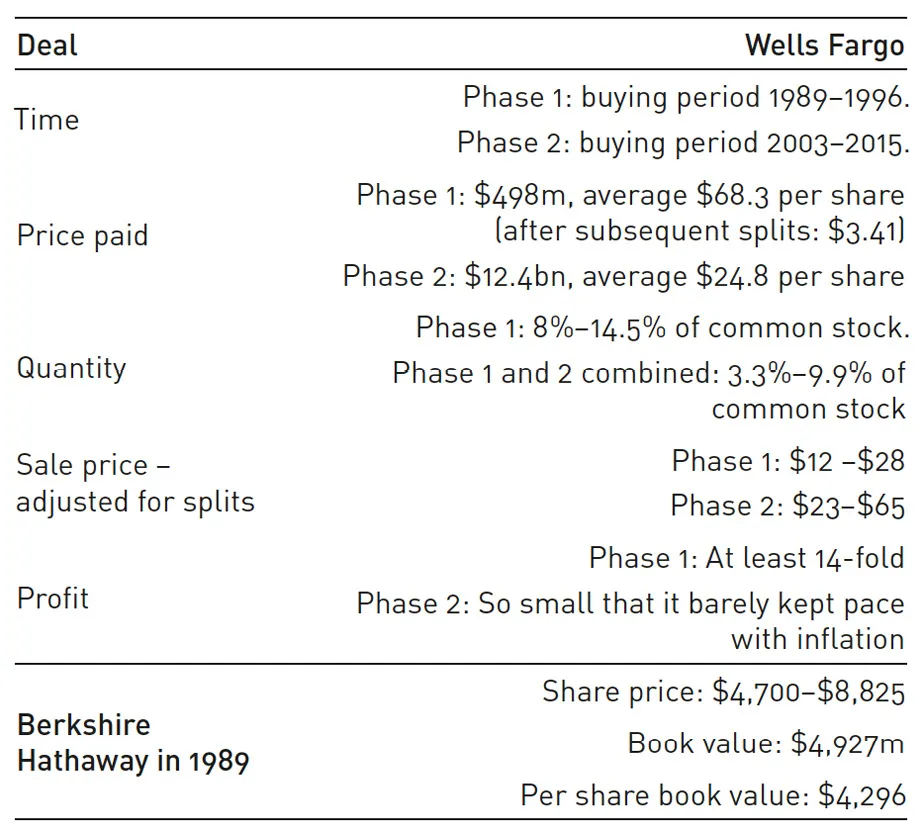

When recession struck in 1990, Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger were there to observe both Mr Market’s panic regarding the banking sector and the strengths of Wells Fargo relative to other banks.

Here are some reasons for worry

I’m going to provide a very simplified version of what a bank is and how it is structured. It’s not perfect but will serve to illustrate why Mr Market was correct to fear for the future of many banks in 1989–90.

Imagine you have two and half million dollars – I know, it’s good to dream – and you decide to use that to start a bank. The corporation is registered with $2.5m shares of common stock as its equity capital. The magic of banks is that most of the money for lending comes not from shareholders but from other people. As a bank owner you can make profit by paying low/no interest on money attracted to cheque or deposit accounts, and then lend that money out to individuals or companies at higher rates.

Let’s imagine that you establish 455 branches throughout California and a few other states. The money flows in at a great rate, and your branch managers get busy attracting families and firms to borrow from the bank. By the end of the year, you have drawn in $46.5m of deposits and lent out $49m.

On the $49m ‘assets’ the bank is, on average, earning such a high interest rate that for every dollar of loan each year it receives 5c more than what has to be paid in interest to attract that dollar as a deposit. That is, the ‘net interest margin’ is 5%.

If you were earning 5c only on each of your original $2.5m, that would amount to only $0.125m each year. But this is where the beauty of a bank’s leverage comes in. You are not earning 5% of $2.5m, but 5% on $49m, i.e., $2.45m.

So, on your original capital of $2.5m you receive annually $2.45m, almost a 100% return per year. But we haven’t yet taken into account the cost of 19,500 staff and maintaining all those buildings, etc. After doing that we find that the net income as a percentage of common stockholder equity is 24.49%, i.e., about $0.6m.

Th...