![]()

Fundamental Properties of Light

![]()

Light surrounds us during most of our conscious life, but many of us observe it only casually. We take delight in watching a sunset, in seeing multicolored city light reflect in the rippled surface of a lake, in observing sunlight filter through the foliage of a forest and cast bright dancing spots on the ground below. Some of the physical processes involved here (such as reflection and straight-line propagation) are a matter of common sense; but most of us still concur with Samuel Johnson’s remark, “We all know what light is; but it is not easy to tell what it is.”

The nature of light has been a topic of great concern and interest throughout history. So important was light that in the third verse of the Bible we find God creating it as the first act of creation, and toward the end of the Bible we find the statement “God is light. ’’ It was one of the topics of which the ancient Greeks already had some knowledge, and the study of light really came to flower in medieval times under the Arabs and later under the European scientists. Light was a major ingredient in the development of modern science beginning with Galileo. Yet as late as the eighteenth century Benjamin Franklin could say, “About light I am in the dark,” and even today the study of light continues to have a major influence on current physics. However, we shall not follow an historical path to develop the main ideas about light but instead shall use the well-tested method of scientists to discover what light does, and thereby understand what it is.

A. Which way does light go?

When we use a phrase like “Cast a glance at this picture,” we pretend that something goes from our eyes to the picture. People who believe in x-ray vision or the “evil eye” may think this is really how light moves (Fig. 1.1). The Greeks of Plato’s time thought light and mind were both made of fire, and that perception was the meeting of the “inner fire” (mind) emitted by the eyes, with the “outer fire” (light)—as Richard Wilbur has written:

The Greeks were wrong who said our eyes have rays;

Not from these sockets or these sparkling poles

Comes the illumination of our days.

It was the sun that bored these two blue holes.

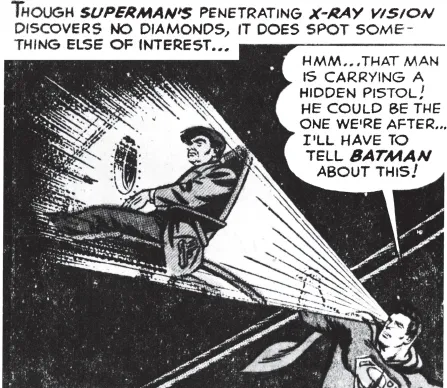

FIGURE 1.1

Superman's x-ray vision comes from his eyes, but the rest of us can only see if light comes toward our eyes.

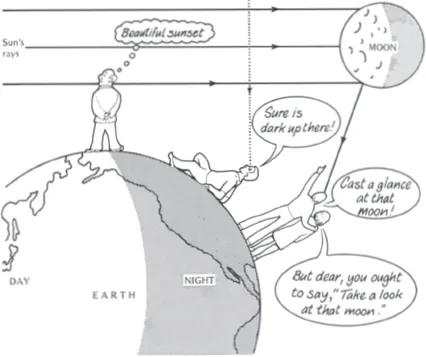

FIGURE 1.2

The void of space looks dark at night even though lightbeams are crossing it.

Nowadays we know that, in order to see something, light has to enter our eyes. But to prove this, would we have to observe light “on its way,” as one can observe a football flying in the air? No! To show that light comes from the sun, through your window, falls on your book, and then enters your eyes, you only need to observe what happens when you draw the curtains: the room becomes dark, but it is still bright outside. If light went the other way, it should get darker outside the window, and stay bright inside, when the curtains are closed.

So we agree that light goes from the source (sun, light blub, etc.), to the object (book or whatever), bounces off or travels through the object (as in the case of glass), and goes to the detector (eye). Sometimes the source is the same as the object. Light goes directly to the eye from these sources, or self-luminous objects. This is how we see lightning bolts, fireflies, candle flames, neon signs, and television.

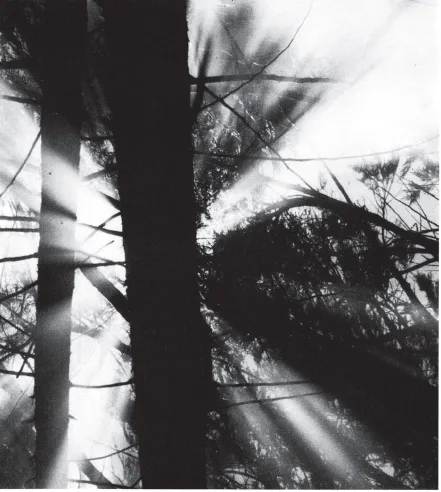

FIGURE 1.3

Scattering in the atmosphere makes shafts of sunlight visible.

Why make a special point about this apparently trivial behavior of light? Consider this consequence: if no light gets to your eyes, you don’t see anything, no matter how much light there is around. You can’t see a beam of light that isn’t directed at you, even though it may be passing “right in front of your nose.” When you look at the stars at night, you are looking “through” the sun’s rays (Fig. 1.2), but you don’t see these rays—unless their direction is changed by an object such as the moon, so that they come at you and fall in your eye.

But you do see lightbeams like those in Figure 1.3! However, this is only because there are small particles (dust, mist, etc.) in the atmosphere that redirect the light so it can fall into your eyes. The clearer and more free of particles the air, the less of a beam can be seen. In the vacuum of space, a beam that is not directed at the observer cannot be seen at all.

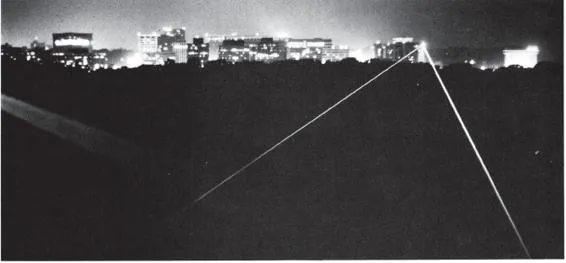

FIGURE 1.4

“Irish lights,” laser art by Rockne Krebs, shows the straightness and beauty of simple light beams.

When light falls on most ordinary objects, some of it is redirected (scattered) into any direction you please. Thus, no matter where your eye is, you can see the object. You can seen an object only if it scatters light. Things like mirrors and windowpanes do not scatter much and are, therefore, difficult to see, as anyone will confirm who has ever tried to walk through a very clean but closed glass door.

The misty or dusty air in which we can see “rays of light” shows us another property of light: it travels in straight lines (Fig. 1.4). The searchlight beam is straight for many miles, and does not droop down due to the earth’s gravity, as a material rod or a projectile would (but see Sec. 15.5C). So we agree that light goes in straight lines— unless it hits some object that changes its direction.

B. The speed of light

If light travels from one place to another, how fast does it go?

Clearly it must go at a pretty good clip, because there is no noticeable delay between, say, turning on a flashlight and seeing its beam hit a distant object. To get a significant delay, we must let light travel very great distances.

“Our eyes register the light of dead stars.” So André Schwarz-Bart begins his novel, The Last of the Just. The physics of the statement is that it takes years for the light of a star to reach us, and during that time the star may burn out. The light that made the photograph of distant galaxies in Figure 1.5 left the galaxies over a billion years before it reached the film.

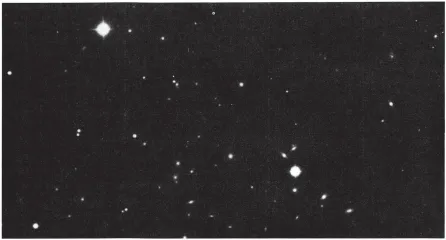

FIGURE 1.5

Each star-like object in this photograph of the Corona Borealis is actually a galaxy, over a billion light years distant. In Thornton Wilder's Our Town, one of the characters expresses his feelings about looking at such galaxies whose light had left so long ago: “And my Joel—who knew the stars—he used to say it took millions of years for that little speck o' light to git down to earth. Don't seem like a body could believe it, but that's what he used to say—millions of years.”

That is, light does take time to get from one place to another. This much seems to have been believed by the Greek philosopher Empedocles, but it was only proved two millennia later. Although more delicate, the proof was analogous to the everyday demonstration that sound takes time to get from one point to another. You can measure the speed of sound by an echo technique: yell, and notice how long it takes for the sound to reflect from a distant wall and return as an echo. You’ll find that it takes sound about five seconds to travel a mile in air.

Light travels much faster than sound. In the thirteenth century, Roger Bacon pointed out that if we see someone at a distance bang a hammer, we see the hammer blow before we hear the sound. In Huck-leberry Finn, Huck observes this on the Mississippi River:

Next you’d see a raft sliding by, away off yonder, and maybe a galoot on it chopping . . . you’d see the ax flash and come down—you don’...