eBook - ePub

The GEOLOGY OF BRITAIN

An Introduction

Peter Toghill

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 224 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

The GEOLOGY OF BRITAIN

An Introduction

Peter Toghill

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

This book is a geological history of Britain from over 2, 000 million years ago to the present day and describes the enormous variety of rocks, minerals and fossils that form this fascinating island. An introductory chapter covers the fundamental principles of geology. Further chapters describe the rocks, minerals and fossils of the recognised periods of geological time, and the areas where they are found today. This book is written for the lay person interested in the great variety of Britain's rocks and landscapes but also includes a wealth of information for students at all levels.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist The GEOLOGY OF BRITAIN als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu The GEOLOGY OF BRITAIN von Peter Toghill im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Physical Sciences & Geology & Earth Sciences. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

CHAPTER 1

BRITAIN DURING THE PRECAMBRIAN

The word Precambrian means exactly what its name suggests – it refers to the time before the Cambrian, and thus all rocks formed during this period are called Precambrian. Rocks of this age were originally considered to be devoid of fossils, and called Azoic (without life), and the Precambrian-Cambrian boundary was initially drawn at the base of the first rock sequences with abundant and varied life forms. We now have rare but widespread evidence for marine plants and soft bodied animals within Precambrian strata, and we may eventually find the ancestors of the abundant hard-shelled life forms of the Cambrian period.

The enormous period covered by the Precambrian stretches over 4000 million years from the origin of the Earth’s crust at around 4600 Ma to the start of the Cambrian at 544 Ma. The rarity of Precambrian fossils means that we cannot divide up this huge period as we can the Cambrian and later periods. However, there is a division into an older almost wholly metamorphic sequence called the Archaean (older than 2500 Ma) and a younger sequence which contains a good deal of sedimentary rock and some fossils, called the Proterozoic.

The metamorphic Archaean rocks form the basement to all continents but come to the surface where erosion and earth movements have resulted in their exposure. Huge outcrops occur in the so-called shield areas – Canadian Shield, the Baltic Shield, etc.

In Britain we have a very important area of these ancient Archaean rocks in north-western Scotland and the Outer Hebrides, as well as in the Channel Isles. Large areas of the younger Proterozoic Precambrian rocks occur in the Highlands of Scotland, and smaller outcrops are found in North and South Wales, Shropshire and the English Midlands.

Scotland

Britain’s oldest rocks – north-west Scotland

The oldest rocks in Britain are ancient gneisses found in the far north-west of Scotland which form a coastal outcrop from the south-eastern corner of Skye and Loch Hourn, northwards on the mainland, to Cape Wrath. They also occur extensively on the Outer Hebridean islands of Harris and Lewis; in fact they are generally called the Lewisian Gneisses. Small outcrops occur on the inner Hebridean islands of Tiree, Coll, Iona and Islay. Some of the gneisses are Archaean, others belong to the early Proterozoic.

FIG. 11. Britain’s oldest rocks. TOP: 2000-million-year-old Lewisian Gneiss, north shore Loch Torridon, Wester Ross. BOTTOM: Lewisian Gneiss near Loch Maree, Wester Ross, with Torridon Sandstone in background.

These intensely altered Archaean rocks have suffered various episodes of metamorphism but started life as a sequence of igneous rocks with some sedimentary rocks. In 1994 the age of the Lewisian Gneiss at Gruinard Bay on the mainland was given as 3300 million years old, but later work suggests a date of 2900 to 2750 million years for the oldest parts of the Lewisian. This compares with Archaean rocks in Canada which are the oldest terrestrial rocks so far dated, at 4000 million years.

It is worth going to the far north-west of Scotland (fig. 11) and standing on, and touching, these ancient rocks, and then considering what they were like before they were metamorphosed at 3000 Ma. What was the world’s surface like in those times? Geologists now consider that it was a time when continents were being built, the atmosphere had no oxygen, and there were no life forms of any complexity.

Within the Lewisian Gneiss are two major groups of metamorphic rocks ranging in age from 2900 to about 1800 million years. The older group is called Scourian, after the village of Scourie in the far northwest of Sutherland, and the younger is called Laxfordian, after Loch Laxford, even further north. The Scourian are usually coarsely banded pink and white gneisses, rich in quartz and feldspar, but sometimes darker. They are derived from igneous rocks. Included in these gneisses in places, particularly in the Outer Hebrides, are metamorphosed sedimentary rocks, now quartzites, marbles, and schists. These rocks, which were formed around 2900 Ma were intruded by basic dykes dated at 2200 Ma, and then in some areas the older rocks were affected by the Laxfordian metamorphism at around 1800 Ma.

The Laxfordian Gneisses really represent a reworking of older rocks, as well as the dykes which are often highly deformed. However, some of the Laxfordian Gneisses include metamorphosed sediments of post Scourian age at c 2000 Ma.

The first (and oldest) unconformity that we come across in Britain is that separating the Lewisian Gneiss in north-west Scotland from a remarkable group of overlying sandstones – the Torridon Sandstone Group (fig. 12). This unmetamorphosed sequence of coarse red and brown sandstones is up to 10 km thick and in many areas of the far north-west is horizontal, resting with a marked unconformity on a deeply eroded Lewisian Gneiss landscape with relief up to 400 m (fig. 13). The sandstones are of late Precambrian (Proterozoic) age and have been dated at around 1000–770 Ma. Hundreds of millions of years of erosion affected the gneisses before the sandstones were laid down on top of them. The red Torridon Sandstone appears to be river and lake deposits and the sediments indicate an arid climate close to the equator. It is possible, by studying the ancient magnetic field present in rocks, to find out where they were formed in relation to the magnetic pole, and these Torridon Sandstones indicate a latitude of around 15°N.

FIG. 12. Torridon Sandstone. Applecross Mountains above Loch Kishorn, Wester Ross.

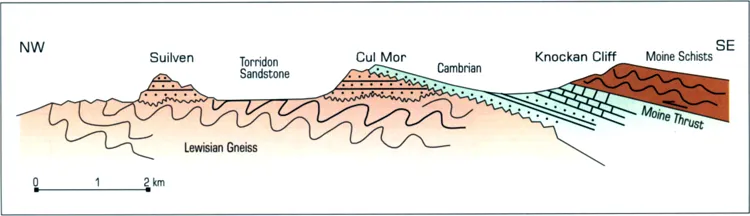

FIG. 13. Cross-section through the Precambrian and Cambrian rocks of north-west Scotland.

The remarkable mountains of north-west Scotland – including Suilven and Canisp – are formed of great terraces of these sandstones, and standing on their slopes one can look north-west across the lake-dotted Lewisian landscape; this really is an exhumed Precambrian landscape.

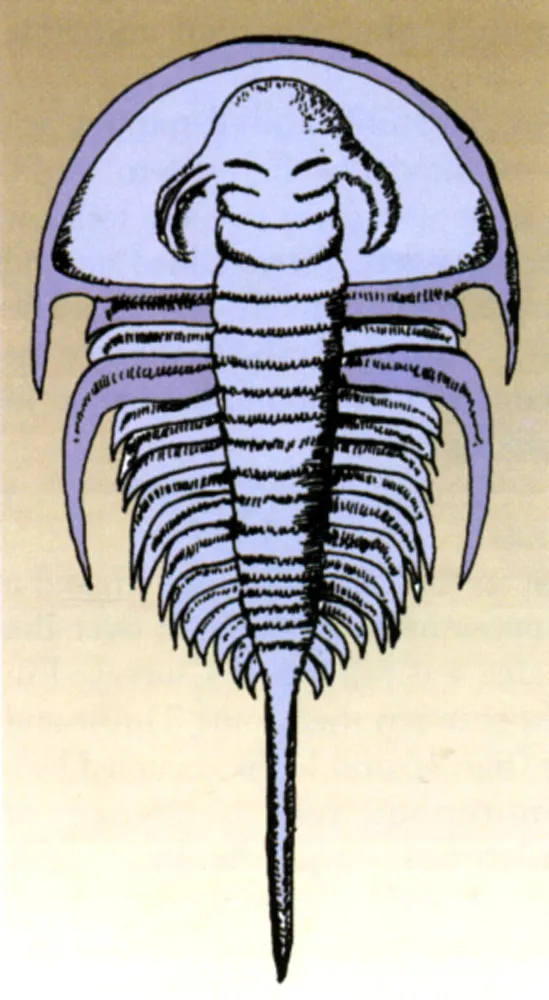

This whole area was inundated by the sea at the start of the Cambrian period at around 544 Ma and here we find our next unconformity with white Cambrian sandstones, the Eriboll Quartzite, resting on eroded Torridon Sandstone (fig. 13), around Loch Assynt. The Cambrian quartzites are followed by sandstones, which have trilobites in them (fig. 14) – the first abundant marine animals – and these are followed by tropical limestones (Durness Limestones) which continue into the early Ordovician.

On plate tectonic evidence we now believe this whole area of north-west Scotland was part of the eastern seaboard of North America, an area geologists call Laurentia, as a new ocean, the Iapetus Ocean, opened up between Scotland and Scandinavia close to the equator. At this time southern Britain was thousands of kilometres away to the south near to the Antarctic Circle (chapter 2, fig. 27).

This narrow area of north-west Scotland is separated geologically from the rest of the northern Highlands (fig. 13) by a major fault which is inclined south-east at a very low angle. This is called the Moine Thrust and was formed during the Ordovician Period at around 480 Ma or more probably in the late Silurian Period around 430 Ma. The sequence of ancient rocks here created great problems for the early geologists of the nineteenth century before the discovery of the Moine Thrust. The Law of Superposition states quite simply that in an ascending sequence of strata the oldest are at the bottom and the youngest at the top. When the sequence was first studied and worked out (fig. 13) it appeared that unaltered sedimentary sandstones and limestones passed up into high grade schists. The problem was to explain how unaltered sedimentary rocks could be overlain without a break by metamorphic rocks. The classic area for studying this problem, and the place where it was solved, was south of Loch Assynt.

At Knockan Cliff (now a nature reserve) the junction can be examined and limestones can be seen to be overlaid by schists. The discovery in 1882 of Cambrian fossils (fig. 14) by Charles Lapworth in the unaltered sediments created even more of a problem because it suggested that the overlying schists were Cambrian. A close look at the junction shows a layer of fine flinty rock called mylonite, a crush rock caused by grinding along a fault plane. This marks the position of the Moine Thrust. Mapping over the whole area shows that the Moine Schists are older rocks occupying a huge area to the south-east, which were thrust north-west over younger rocks during the Caledonian orogeny around 430 Ma. There is an excellent view from Knockan Cliff west and north over the Cambrian, Torridonian and Lewisian rocks. A number of other thrusts have been mapped around here which are branches of the main Moine Thrust; well-known ones include the Glencoul and Sole Thrusts.

FIG. 14. Olenellus lapworthi, x3. A Cambrian trilobite from north-west Scotland.

FIG. 15. Intense folding i...