![]()

Chapter 1

INCORPORATING INTERNATIONAL INFLUENCES

JAPAN IS GENERALLY CONSIDERED A BORROWing culture drawing on global precedents imported and adapted for domestic use. Prior to the Meiji period China was the predominant source, during Meiji modernization Europe became the predominant source and after WWII the United States became the prominent source. Tracing international influences, David Pollack noted a shift in orientation from wakan (Japanese wa and Chinese kan), synthesis, to wayo (Japanese wa and Western yo), combinations.1 Dialogues with Western developments were most pronounced in the Meiji period, with study tours such as the Iwakura mission (1871–73) scouring the globe for models of modernization – from British navy and German army to French judicial and American banking systems. Similarly, the architecture of Meiji modernization represented an eclectic importation of Western historicist architectural models introduced via Conder’s Architecture Department at Tokyo Imperial University, pattern books and through other channels.

Meiji importation from the West has often been reduced to imitation, but Eleanor Westney reframed common critiques, arguing that incorporation of foreign models produced innovations due to imperfect information, selective emulation, scalar differences, the influence of alternative implicit models and lack of supporting organizations. She also demonstrated that foreign models were translated to Japan based on access to information and on assumed prestige, not necessarily based on optimal compatibility.2 Thomas Water’s John Nash-inspired Ginza Bricktown (1872–78), which was hailed as a fireproof showpiece of modernity and city planning, succumbing to the 1923 Great Kanto earthquake was but one architectural example supporting Westney’s caution on compatibility.

Prior to the 1923 earthquake, models for Japanese architecture began to shift from European historicism, which proliferated in the Meiji period, to a burgeoning modernism emerging in the Taisho period. The new round of translating modern approaches from abroad continued to be spurred by the combination of information access, international travel and assumed prestige. Modernism brought new styles, new building techniques, such as reinforced concrete, and new ideologies.

Following Westney, this chapter explores innovative and creative uses of inspirational international idioms in the development of Japanese modern architecture. The chapter traces the incorporation of global influences from the pre-war reorientation from European historicism to modernism to post-war shifts from Germanic to Corbusian modern influences. Subsequent periods reflect Japanese engagement with prevailing postmodern critiques of modernism and their reverberations across Japanese developments. A series of contemporary projects demonstrate ongoing dialogues with international trends and the reconfiguration of canonical modern idioms into new alternatives.

Pre-War Projects (c. 1920–40)

Accompanying liberalization during the Taisho period, modern-style architecture and modern architectural movements (such as the Bunri-ha) emerged. The Bunri-ha followed their European counterparts in rejecting imitation of past styles and promoting a new architecture reflective of new conditions facing Japanese society. Bunri-ha members modelled their pursuits on European developments, which they encountered through lectures by Chuta Ito and others at Tokyo Imperial University, accessible international publications and subsequent travel to witness global developments.

This section focuses on two prominent figures and their exemplary projects. Kikuji Ishimoto was a founding member of the Bunri-ha and Bunzo Yamaguchi was Ishimoto’s collaborator and subsequent contributor to the Sousha architectural movement. Both architects reflect the strong Germanic influences shaping pre-war Japanese modernism. Ishimoto was inspired by the Vienna Secessionists and upheld Bruno Taut, Hans Poelzig and Walter Gropius, whom he introduced to Japan, as exemplars. Yamaguchi worked for Gropius and translated those experiences into the Japanese context. Ishimoto’s Asahi newspaper building (1927) was his ‘debut’ project and Yamaguchi’s Yamada House (1934) his most prominent residential project. Both architects and projects represent the richness of pre-war Japanese modern architecture achieved through integration of international influences.

While rejecting Meiji architectural practices, Ishimoto expanded Meiji precedents, embarking on a privately funded international study tour documented in his Architecture Notes (1924) illustrated travelogue. The publication and its offshoots provided a pulpit for his promotion of European modern styles in Japan through the Bunri-ha (1920–27) and subsequently through the Japan International Architecture Association (1927–33). Complementing Architecture Notes, Ishimoto produced a series of essays historicizing the new modern style and articulating components of the new architectural aesthetics. For example, in ‘Concerning Architectural Beauty’ (1924) he echoed European modernist maxims, advocating the achievement of beauty through form, balance, proportion and the functional arrangement of elements, not through decorative historicist application that was not integral to the form of the building. In the essay Ishimoto reinforced the Architecture Notes menagerie of admirable movements and personalities he felt were transforming architectural aesthetics – Walter Gropius, the Bauhaus, Erich Mendelsohn, Constructivism, Le Corbusier, J.J.P. Oud, Willem Dudok and Josef Hoffmann – and claimed: ‘It seems to me that they are expressing a new style with contemporary architectural aesthetics. I am sure that from the mixture of those things an international architecture style will develop.’3 This statement prefigured Ishimoto’s creative combination of their ideas in his manifestations of modern architecture in Japan exemplified by his Asahi newspaper (1927) and Shirokiya department store (1928–32) buildings.

Incorporating International Influences

From Conder’s introduction of European historicist styles to contemporary pluralist positions shaped by global developments, Diagram 1.1 tracks key international influences. Modern masters and movements from abroad shaped the foundation of modernism in Japan. Increasing postmodern permutations were shaped by varied architectural approaches, ranging from the introduction of irony to contextualist critiques of modernism to new configurations influenced by poststructuralist theories of deconstruction and deconstructivist architects. As illustrated, there has been an increasing accumulation of concurrent approaches creating a rich panoply of globally interconnected contemporary Japanese architecture.

(Diagram produced in conjunction with Philip Chang, Pricilla Heung and Colby Vexler)

Diagram 1.1 Incorporating international influences.

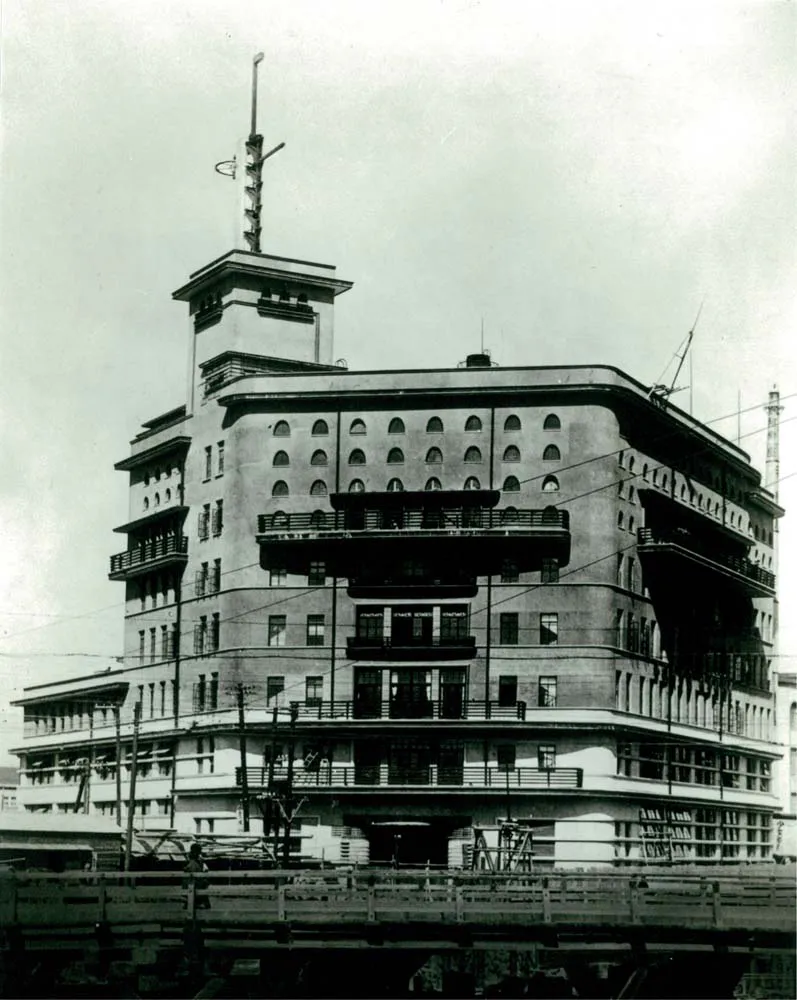

The 1923 earthquake caused widespread destruction across Tokyo, but created new opportunities for modern architecture during the reconstruction period, including the spread of reinforced concrete structures. Ishimoto’s Asahi project provided a replacement facility for the progressive newspaper, which sought to distinguish itself by a contemporary image in contrast to its conservative competitors who maintained their preference for European historicist buildings. The Asahi building was noted for its mustard and blue coloration, rounded windows, and geometric patterned stained-glass windows.

Fig. 1.1 Asahi newspaper building, Tokyo (1927). (Courtesy of Ishimoto Architectural & Engineering Inc.)

Asahi incorporated Ishimoto’s Germanic influences (Fig. 1.1). The massing, rounded windows and curved corners of the project resonated strongly with Poelzig’s Werder Mill (1906–08). The building echoed Gropius’s Chicago Tribune entry (1922) in the horizontal banding of the balconies, with further Bauhaus influence in the articulation of the theatre. Yet the architectural press described Asahi as the first Japanese building modelled on Mendelsohn’s style. Ishimoto countered the association with Mendelsohn by characterizing the project as a ‘proposal of passage from a general 1900s style to international architecture’ that helped usher in Japanese modernism.4

Yamaguchi joined the Bunri-ha in 1923, but in the aftermath of the earthquake he left to launch Sousha as a new architectural movement organized by socialist working-class draughtsmen promoting new directions for architecture. Sousha (1923–30) followed the Bunri-ha in employing exhibitions and publications to disseminate their ideas, but contrasted with the predominantly university-educated elite membership of the Bunri-ha. Yamaguchi worked with Ishimoto at Takenaka Corporation, which he left with Ishimoto to undertake the Asahi and Shirokiya projects. Yamaguchi was responsible for the working drawings of both projects. He also designed the entrance, the president’s room, the manager’s room, the stairs and the curtain for the auditorium in Asahi and produced the prominent rendering of Shirokiya. Yamaguchi left Ishimoto in 1929 and went to Europe in 1930, where he enrolled in Berlin University while concurrently working for Gropius, who had recently left the Bauhaus. Yamaguchi worked on the Palace of the Soviets competition (1931), AEG Workers Housing and Karlsruhe Housing projects (1932), and overlapped with the production of projects such as the Siemensstadt Housing Estate (1931). Yamaguchi returned to Tokyo in 1932 and started his own office in 1934, which evolved into the Research Institute of Architecture (RIA) after WWII.5

Fig. 1.2 Yamada House, Kita Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture (1934), exterior. (Courtesy of RIA, photo by Bunzo Yamaguchi)

Yamada House (1934) was an early Yamaguchi project and an emblematic example of modern architecture in Japan on a par with Sutemi Horiguchi’s Dutch-inspired Kikawa Residence (1930) and Antonin Raymond’s Tetsuma Akaboshi House (1934). David Stewart described Yamada House as ‘one of the wittiest and most successful double-takes in the history of modern Japanese design’6 (Fig. 1.2). The house appeared to be a reinforced concrete structure typical of modern dwellings, but was constructed from timber clad in white mortar plaster combined with a steel colonnade.

Fig. 1.3 Yamada House, interior foyer. (Courtesy of RIA, photo by Bunzo Yamaguchi)

In addition to the lingering influences from working for Gropius, Yamada House also echoed features from Lovell Health House (1929) by Richard Neutra, whom Yamaguchi met in Japan before heading to Europe. On the exterior the slender steel colonnade and terrace balconies drew on Neutra. On the interior the vertical extension of the double-height stair foyer and the corresponding horizontal expansion of adjacent rooms resonated with Neutra (Fig. 1.3). Yet in Yamada House the L-shaped plan produced visual horizontal extension in two directions from the foyer to both the dining and living areas. The massing of the south façade with a two-storey volume flanked by porch and roof terrace over the library similarly coordinated the simultaneous horizontal and vertical extension of the house.

Yamada House adhered to many of the principles that Gropius set out in his 1931 Architectural Forum essay ‘The Small House of Today’, accommodating the free functional arrangement of rooms, flexibility, efficient circulation, clear separation between public and private activities and southern solar access.7 However, Y...