1 On Noticing What You See and Hear

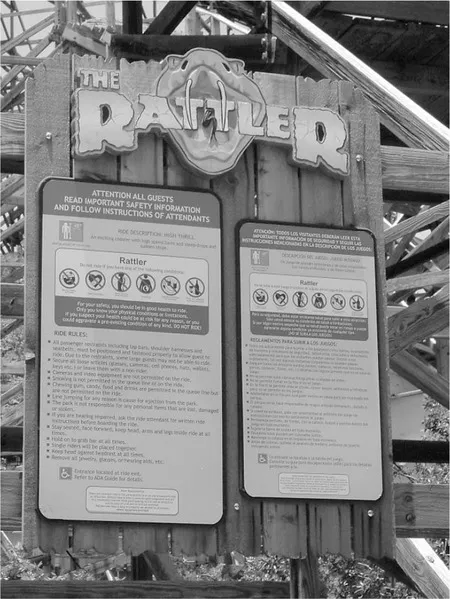

Recently, I went to an amusement park outside of San Antonio, down the road from where I live. Take a look at Figure 1.1, a photograph of a sign near the entrance to a particularly scary roller coaster.

It’s the kind of thing you might glance at and not give a second thought to, but take a harder look. Consider the context: San Antonio, one of the ten largest cities in the United States, is also a city in which the majority of people are of Latino, Hispanic, or Spanish-speaking heritage. So why is the warning sign in Spanish smaller than the one in English? Perhaps of more interest is the question of what that difference does to people who see it. Think about what message size conveys all by itself.

As I write this, I am in Cape Town, South Africa, for a conference. The conference organizer left me this note when I arrived: “Welcome! I hope your travels were pleasant. As you get settled, give me a call on 082 731 xxxx. I am just around the corner, and perhaps we can meet up for a coffee on Tuesday or Wednesday.”

It’s a perfectly fine note, but it contains a couple of words that I would not have used had I written it. He asks me to call him “on” such and such a number. I would have asked someone to call me “at” a given number. And he wants to have “a coffee.” I would have said “coffee.” Not a big deal, but it’s interesting to me. I don’t know that much about this person. He teaches at a large Midwestern university in the United States, as have I most of my life, but I don’t know if he’s from the Midwest. So I’m wondering what the source of our minor language differences would be. As a frequent traveler to South Africa, has he adopted a South African, British, or European way of speaking? Or does his usage reflect some other pattern? What do my preferred wordings say about me? Not the most earthshaking questions, but their answers reveal some interesting things about where he and I are from and what our social allegiances are.

Most people wouldn’t even notice this wording, and you might be wondering why I would do so. And you might not have paid much attention to the signs in front of the roller coaster in our first example. But I think that being in the habit of noticing what people say and write and being able to reflect on what these messages mean is a useful habit to pick up. It is a habit of close reading, and this is a book about how to train yourself to be a good close reader. In Chapter 1, I argue that close reading is the mindful, disciplined reading of an object with a view to deeper understanding of its meanings. The objects we will learn to read closely are called texts or messages. It’s important to be able to read closely because it helps us to see things about messages, such as the difference in size of the warning signs, that do make a difference and do affect how people think.

These two examples—the roller coaster sign and my colleague’s note—show us two dimensions in which close reading is important. First, it is important socially. As citizens, as people active in public life, we need to know how the messages we encounter may influence the public in important ways. We all know that instances of racism and ethnic inequality occur from time to time, for example. Rarely will we find these and other problems openly and explicitly expressed or perpetuated. Instead, we are more likely to be socially influenced in small ways—such as through signs in an amusement park. A single sign in an amusement park that makes English bigger, for better or for worse, will not by itself create social and political attitudes. But a day’s or a month’s experiences of such signs might. As public citizens, we at least need to be vigilant as to the meanings and possible effects of the messages we encounter. Close reading can help us do that. We can thus claim that the ability to read closely is a public, civic responsibility for all of us.

Second, close reading is important personally. My ability to get along with my friend may well be improved if I can fully understand the ways his language use differs from mine. Paying attention to differences may alert me to other language variations I encounter, such as the British, in which one lives “in Hampton Street,” as opposed to the American usage, in which one lives “on Hampton Street.” We have all probably had other experiences in which the ability to read people and their messages was important. When we were young, we likely needed to pay close attention to our parents and read their tones of voice, words, and actions so that we could learn, grow, and stay out of trouble. Many of us have had difficult bosses or supervisors who needed to be closely read to make the workday go more smoothly. Learning how to read the messages of others more closely is therefore also a valuable personal skill.

Many of the readers of this book are college students. Students have particular need of skills in close reading. If you are a student, seldom in your life will you be in so diverse a group of people, and the ability to read others and their messages is important. Many of you will keep blogs or will post messages through such currently popular sites as Facebook or Twitter. The ability to read these very short messages of others may alert you to important dimensions of personality or social beliefs of people you are getting to know or to changes in how old friends think as they go through college. Is a recent blog posting sarcastic? Should you take it seriously? Is the poster angry? Or perhaps seductive? An ability to read closely may help you answer questions like these. And of course, the ability to read a syllabus or course assignment carefully and understand it can make a big difference in your success or failure in college.

Chapters 1 and 2 introduce you to the general subject of close reading. In this first chapter, the section titled “Being a Reader, Being a Critic” explains in more detail what I mean by close reading, and it introduces you to the idea that we read closely in our daily lives. This book will help you to read closely in more disciplined and systematic ways. Further, this chapter discusses what it means to be a critic. It also introduces the idea of rhetoric, or persuasion, and why a better understanding of the rhetoric of what we read is an important goal of close reading.

Chapter 2 explains the concepts of theories, methods, and techniques. For many, these may sound like three difficult concepts, but actually, we use them in everyday life. I explain that a theory is like a map to a text and that you have likely already learned several theories about how texts work. If you have studied small group communication, for instance, you may have learned theories that help you navigate a group meeting, understanding what is going on as people communicate. A method is the vehicle you use to navigate a text, so to speak, following the theory’s map. You might use methods of ethnography, for instance, to study a small group as it meets. And techniques are habits, tricks, or skills you acquire to study things—for instance, ways of recording conversations in small groups. These key terms are organized conceptually so that you can see how you can use the knowledge you have already gained in your education to support close readings. Additionally, these and other key terms and concepts are italicized in the text and summarized at the end of this chapter.

Chapter 2 also explains the ethical implications of close reading for both critic and audience. Critics and their audiences risk something when they read closely, and they ask others to take similar risks—hence, the ethical implications. The chapter discusses both inductive and deductive theories and shows how methods connect to theories. Finally, the chapter introduces the idea of techniques, which are the focus of the rest of the book.

Chapter 3 explores the idea of form. You will learn that form is the structure, the pattern, that organizes a text. Techniques for detecting and understanding form in texts are explained. The three main techniques you will study in Chapter 3 are narrative, genre, and persona. Narrative is, as you will learn, the storylike form of a text. Three elements of narrative are found in texts: coherence and sequence, tension and resolution, and alignment and opposition. A genre is a recurring type of text within a context. You will learn that a genre has recurring situational and stylistic responses to recurring kinds of contexts. One can also think of a genre as a recurring type of narrative. Our final technique is the detection of personae, and you will learn that a persona is a role, much like a character in a narrative, that someone (such as a reader or critic) plays in connection to a text.

Chapter 4 explains techniques of exploring ideology by analyzing the arguments in texts. Ideology is a systematic network of beliefs, commitments, values, and assumptions that influence how power is maintained, struggled over, and resisted. Ideologies are supported by and also revealed through argument. Argument is a process by which speakers and writers, together with audiences, make claims about what people should do and assemble reasons why people should do those things. You will learn that some good techniques for detecting the arguments that establish ideologies are found in these questions to ask of a text: What should the reader think or do? What must the text ask the reader to assume? How does the reader know what the text claims? Who is empowered or disempowered? With these techniques, we may think more critically and productively about the good reasons texts give us for believing what they want us to believe. The chapter talks about how a close reading might reveal how ideologies of gender, race, sexual orientation, and so forth are being presented or countered in texts.

Chapter 5 uses the idea of transformations to organize some techniques for looking beneath the surface of texts, for seeing what might not be apparent at first glance. We will see that transformations are ways in which the ordinary, literal meanings of signs and images are turned—reversed, changed, altered—by readers of texts. Some transformations you will study are called tropes, and we will examine techniques for identifying the important, common tropes called metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche, and irony.

Chapter 6 is a single close reading, which illustrates how techniques from across the chapters might be used. The text read will be a cartoon from the strip Candorville that appeared shortly before President Obama’s inauguration.

Finally, a conclusion reviews these techniques to sum up how they might be used and what we have learned.

Close reading in a disciplined way is a skill that will serve you well for the rest of your life. By no means is it merely an academic exercise. In a world in which messages increasingly ask us to believe, accept, buy, and follow, the ability to read texts closely is an indispensable survival skill. Close reading is both personally and socially empowering. Join me now in learning some techniques of close reading.

Being a Reader, Being a Critic

It won’t come as any surprise to you when I point out that you are reading: You are reading this book. Reading is something you do every day, but let’s think for a minute about what that involves. You are looking at this book, an object, that is full of black marks on white paper. Not just any black marks; these marks have meaning. You know what these black marks mean in the English language, and you know how to put together into a coherent message the meanings that these marks suggest. We can think of meaning as the thoughts, feelings, and associations that are suggested by words, images, objects, actions, and messages. Consider this series of ink marks on paper:

DOG

When you read it, certain thoughts, feelings, and associations come into your head, which are what the markings (the letters) mean. That is how all reading works. If you couldn’t find meaning in reading (and sometimes we cannot!), you’d quit doing it.

It’s a remarkable thing about reading that a hundred people who read the same thing will likely find both the same meanings and different meanings. This is true even in ordinary conversation. The last time you said, “I didn’t mean that,” you were complaining that somebody read a meaning in something you said that you would not find there yourself and that you certainly didn’t intend anyone to find. But despite the recurrence of misunderstandings and misreadings, we continue to read books, movies, TV shows, and each other with confidence that we will find enough of the same meanings others would find that we can all make sense of the world together.

Although you know there is a lot of disagreement and “slippage” regarding what messages mean, you are fairly confident that you are finding many of the same meanings in this passage that I, your author, hope you will find there. You are also fairly confident that you are finding many of the same meanings most other people would get from this reading. If somebody else reading this book told you, “You know, the first paragraph is a coded message from that Brummett fellow that the world will end in 2030,” you would be justified in doubting such a reading. Although it’s not foolproof, we read just exactly to discover meanings that we think most other people would also find if they read the same way we did.

There is a whole field of study called semiotics, or semiology, that concerns itself with meaning and how meaning is read. We don’t have time to explore it fully here, but some classic texts, referenced at the end of this book, are by Charles Sanders Peirce, S. I. Hayakawa, and Ferdinand de Saussure. Semiotics studies different kinds and levels of meaning; it is sensitive to the differences in meaning that arise out of personal experience and between personal experience and generally agreed-upon understanding. I encourage you to explore this further if it interests you.

One recurring concern in semiotics is the management of ambiguity in language. Some thinkers believe that language works best when all ambiguity is removed as much as possible (although most recognize that is not possible). Other thinkers believe that ambiguity is of the essence of language and that total precision of meaning is not possible. A close reading may fall on either side of the controversy, although when there is ambiguity in language, close readings can work to reveal the ambiguities and to show slippage in the meanings of a text.

When we read, we do lots of complicated things at once:

- We examine an object (like a book) to figure out some of the things it means.

- We usually (although not always) try to figure out which meanings the person who created that object wanted us to find.

- We usually are interested in finding meanings that other readers who share some of our experiences and contexts would also find.

A reading, then, is an attempt to understand the socially shared meanings that are supported by words, images, objects, actions, and messages. Somebody might well think that my first paragraph means that the end of the world is impending, but that is likely not a socially shared meaning, since hardly anyone else will find that meaning in the paragraph. A reading is an attempt to find reasonable or plausible meanings in a message or object, and readings are done in such a way as to be defensible after the fact. By defensible, I mean that someone can produce evidence to support your reading from the message or from widespread usage. You might defend a reading by saying, for instance, “I read the message this way because of the way these two sentences are phrased,” or, “In the southern United States, most people see that image this way.” There is a connection between the fact that we search for socially shared meanings and the fact that we search for meanings that are also plausible and defensible: In everyday reading, we want to read so that most people who encounter the same message could see the same meanings if they, too, were to read the same things. If you get a party invitation that says “semiformal,” and you show up in suit and tie while your host greets you at the door in a swimsuit, you will surely defend your reading (that is, give evidence for your understanding) of the invitation as correct, as what most people would find in such a message, and as the meaning most people would intend by “semiformal.”

A reader is a meaning detective, and while detectives may often make guesses about the mysteries they try to solve, those are usually educated guesses that can be backed up with evidence; the same is true for the meaning detective of a message. The meanings we detect are the plausible, defensible, socially shared meanings that are supported by a message. Like detectives, though, we can make educated guesses about meaning, and to do so, you must be educated! That is the purpose of this book: to give you some ways to read plausible, socially shared meanings and share them with others in ways you may not now be able to.

It may come as a bit of a surprise when I suggest that you read many other kinds of experiences, some of them clearly messages and some of them not, in ways similar to the way you are reading this book. You see a garden bed all trampled down and read that as meaning that the neigh...