![]()

1.

Historical and cultural context

Product design, as we understand it today, is a relatively young discipline. It is generally recognized that it emerged as an activity during the Industrial Revolution of the mid-eighteenth century. Until then, what is now commonly described as craft production had existed as the sole means of producing objects. Makers of objects were the originators of that design, or guardians of a design handed down through generations of designer-makers, often remaining unchanged or unquestioned. Since the emergence of product design as a profession, the discipline has been characterized by a spirit of reform. A number of individual designers, self-styled movements, and writers have attempted to establish its role in society. This chapter examines the profession’s development within a social, theoretical, and cultural framework from 1750 to the present day.

The Industrial Revolution: 1750s to 1850s

The Industrial Revolution heralded mass production. This industrialization was characterized by factory owners commissioning specialists to supply drawings and instructions that could be interpreted and manufactured by semiskilled or unskilled factory workers, producing goods in large numbers far more economically than the previous craft methods. As the production process became increasingly complex, and the business of making became ever more divorced from the role of determining a product’s form, a profession known as “product designer” emerged whose primary role was to give form to these mass-produced items.

The mid-eighteenth century saw a number of significant industrial developments. For instance, in 1752 Benjamin Franklin (1706–90) discovered electricity and, by 1765, James Watt (1736–1819) had developed the steam engine, which enabled the rapid development of efficient semi-automated factories on a previously unimaginable scale. Without some notable earlier inventions, however, including the spinning jenny and the flying shuttle, some of the later achievements such as Watt’s steam engine might never have been possible. Industrial mass production heralded the production of all sorts of consumer goods and modern transportation systems. The division of labour enabled factory owners to produce goods cheaply, eventually resulting in the workforce being paid low wages and regularly working long hours in horrendous and often dangerous conditions. Inevitably the drive for more and more goods at lower prices led to bitter poverty, poor living conditions, and a miserable life for the working classes.

Josiah Wedgwood

Josiah Wedgwood (1730–95) spent most of his life in the Wedgwood family’s pottery business, which was based in Staffordshire. He was responsible for revolutionizing pottery-manufacturing techniques in order to increase production and sell to a wider market during an era largely characterized by handwork. Faster production led to wider availability and increased affordability. Wedgwood transformed the pottery industry and established a mass-manufacturing production system, where he exploited advertisement by royal association that elevated his pottery’s status. Wedgwood’s approach to manufacturing split areas of labor into a production-line concept, which distinguished design from manufacture and production. Jasperware vase, twentieth century (right).

In the process of transition from handwork to industrial production, the planning of an object began to be separated from work by either hand or machine. Pattern books and portfolios were widely distributed in the mid-eighteenth century in order to solicit and secure orders. Furniture, for example, was produced in advance and offered for sale as finished pieces in larger magazines and sales catalogs. The first known pattern books of the early industrial era in Britain came from Thomas Sheraton (1751–1806) and Thomas Chippendale (1718–79), both of whom were to have a major influence throughout Europe. Design had, therefore, acquired significance not only for production but also for sales. Josiah Wedgwood (1730–95) founded his pottery factory in 1769 in Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire, Britain, to serve not only the aristocracy but to feed a wider market among the middle classes with more everyday pottery.

The Great Reform movements: 1850s to 1914

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the awful conditions in factories led to widespread worker unrest and the formation of workers’ unions and parties. In 1867 Karl Marx (1818–83) wrote Das Kapital, one of the most important socioeconomic books ever produced, in which he analyzed the new structures of industrial production and society. The increasing mechanization of the Industrial Revolution encompassed not only production methods but the products themselves. The nineteenth century was the time of the engineer, and by the middle of that century the United States had taken over the leadership of engineering developments. In 1869, the east and west coasts of America were united by the Union Pacific Railway, and in 1874 the first electric streetcar debuted in New York. The following year, Thomas Edison (1847–1931) developed the incandescent lightbulb and the microphone. Since 1851, Isaac Merrit Singer (1811–75) had been producing the household sewing machine, and Alexander Graham Bell (1847–1922) exhibited a working telephone at the Philadelphia World’s Fair in 1876.

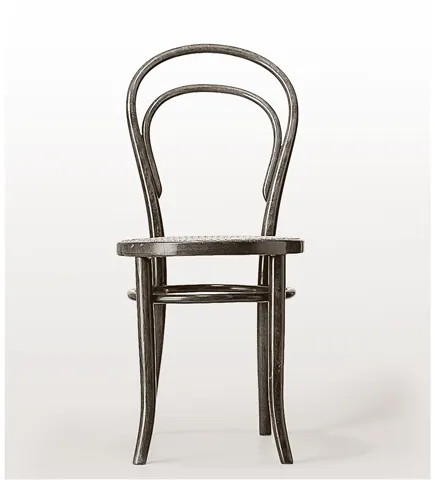

Chair 214, by Michael Thonet, 1859. The famous coffee house chair is still influential today, since some 50 million were produced up until 1930. It was awarded a gold medal at the 1867 Paris World’s Fair.

In Europe, at around the same time, a great deal of mechanical furniture was being produced, including swivel chairs and space-saving folding furniture for the increasing number of hair salons and offices that were emerging. In Munich in 1854, Michael Thonet (1796–1871) presented his first bentwood chairs, and by 1859 the Thonet chair No. 214 became the model for all bentwood chairs and a prototype for modern mass-produced furniture.

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, a second wave of industrialization spread across Europe. The technical advances of the century resulted in new methods of production, new commodities, and equipment with new functions.

Arts and Crafts: 1854–1914

A number of significant reform movements emerged during the second half of the nineteenth century that advocated a return to nature and handcraft as an answer to the excessive development of industry, large cities, and mass production. William Morris (1834–96), the father of the Arts and Crafts Movement, was the most important voice for the renewal of artistic handwork. Morris, along with the art critic and philosopher John Ruskin (1819–1900) and the painter and illustrator Walter Crane (1845–1915), took inspiration from the Pre-Raphaelites (a group of English painters, poets, and critics, founded in 1848 by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and others) in their pursuit of a return to nature as well as to clear and simple organic forms. Morris and Ruskin also campaigned for a better quality of life for those living in an industrialized society.

William Morris

William Morris (1834–96) was, among many things, a poet and dreamer, a businessman, and a political campaigner. He had great design and craft skills and executed several pieces of work of outstanding beauty in wallpapers, in printed, woven, and embroidered textiles, and in book production. Morris founded a firm, Morris & Co., to retail furnishings produced in his own workshops, where craftsmen were given free rein. The firm’s products, however, while intended to brighten the lives of ordinary people, were too expensive to sell to any but the wealthy. Anemone wallpaper, nineteenth century (right).

Art Nouveau: 1880–1910

Around the turn of the century, Art Nouveau, a reform movement shaped by the Arts and Crafts philosophy, developed into a fully formed international movement in many of the key centers of Europe, including Paris, Nancy, Brussels, Vienna, Barcelona, Glasgow, Darmstadt, Munich, Dresden, Weimar, and Hagen. Art Nouveau was known by many names throughout Europe. In Britain it was called Decorative Style, in Belgium and France Art Nouveau, in Germany Jugendstil (“youth style”), in Italy the Stile Liberty, in Austria Sezessionsstil, and in Spain Modernista.

A significant amount of Art Nouveau work was influenced by geometrical forms drawn from Japanese art as the Western world discovered Asian culture. This was due in some part to a trade treaty being agreed, in 1854, between the United States and Japan that approved the import of Japanese art after almost 200 years of isolation. At this time, much Japanese art used imagery from nature—birds, insects, and botanical studies of plant life—as primary sources of inspiration. Moreover, Japanese art’s use of flat perspectives and block colouring was a revelation to many Western artists. One of the main aims of Art Nouveau was to transcend the boundary between pure and applied art. Practitioners were supposed to design not just “art” but jewelery, wallpaper, fabric, furniture, tableware, and more. As a response to mass-produced wares, the movement strove for a comprehensive artistic reformation of all areas of life.

Writing desk and chair, by Henri van de Velde,1897–98. The design displays an organic aesthetic common to Art Nouveau.

Christopher Dresser

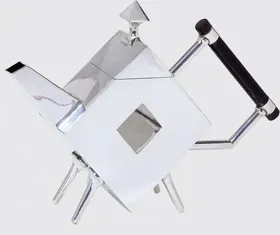

Christopher Dresser (1834–1904) is generally acknowledged as being one of the first independent product designers. Born in Glasgow, he won a place at the newly established Government School of Design at the age of thirteen. This new art training system was set up to improve the standard of British design for industry by joining the disciplines of art and science. Dresser championed design reform in nineteenth-century Britain, while embracing modern manufacturing techniques in the development of a range of products from textiles, ceramics, glass, furniture, and metalware. He was a household name, famed for his promotion of product design as a force for furnishing ordinary people with well-made, efficient, and engaging goods. His commercial success is all the more remarkable as he also pioneered what we now recognize as the spruce, simple, modern aesthetic. Some of Dresser’s products, notably his 1880s metal toast racks, are still in production today. Geometric teapot, 1880 (right).

Victor Horta (1861–1947) and Henri van de Velde (1863–1957) were two of the most famous representatives of Art Nouveau in Belgium. Horta utilized the new materials of iron and glass that had been exploited in the building of London’s Crystal Palace in 1851 and the Eiffel Tower in Paris from 1884 to 1889. He used the floral ornamentation of Art Nouv...