Most social researchers have little difficulty in selecting a broad topic or area for research. They may, for example, identify a gap in our knowledge of some aspect of the social world, or a set of issues whose exploration seems particularly timely, or a particular substantive interest relating to their own experiences; or they may be commissioned by an organization to research a particular set of events, to evaluate a social programme, or to produce evidence to inform policy or practice. However, while identifying a general interest or topic in this way is fairly straightforward, it is much more of a challenge to design an effective project with a clear, relevant and intellectually worthwhile focus to explore your topic. In this chapter we will address the issues involved – and the difficult questions to ask along the way – in moving from a broad or general research interest to a set of research questions which can form the basis for an effective research design. I shall argue that researchers should be clear about what is the essence of their enquiry – the phenomena they want to investigate and understand better – and should express this as an ‘intellectual puzzle’ with a clearly formulated set of research questions from the start, even though they may want to modify these or generate further research questions at a later stage.

KNOWING WHAT YOUR RESEARCH IS ABOUT: SIX IMPORTANT QUESTIONS

It is well known that researchers who are in the early stages of their work often find it very difficult to explain to others briefly but specifically what their research is about. Many can come up with a short but over-general version, such as ‘gender in the classroom’ or ‘the experience of refugees’ or ‘intimacies in the digital world’. Alternatively, most researchers can produce a long and detailed version of their research problem. But the middle course between these two is often very elusive, and the struggle for any researcher, in my view, is to be able to articulate what is the ‘essence’ of their enquiry. I think it is a struggle because, in order to get to this essence, researchers have to ask themselves some difficult questions, and at the outset of research it can feel much easier to avoid these. I think there are six of these difficult questions, and indeed any researcher, whether of a qualitative or quantitative orientation, should address them. Similarly, these apply whether or not the researcher feels they have sole control over the direction and focus of the research. Indeed, where research is commissioned, and in a sense the topic already chosen, these questions are too often overlooked entirely when, arguably, they are even more important to confront.

Each of the questions is produced below in a form that is designed to encourage you as a researcher to interrogate your own assumptions, to systematize them, and possibly to challenge and transform them. While any researcher is unlikely to produce a research design that provides a clearly formulated set of answers to each of these six questions, they nevertheless need to know what the answers are if they are going to produce a good, and worthwhile, research design. All six questions involve asking what your research is about, in different ways.

1. The social world: your ontological perspective

What is the nature of the phenomena, or entities, or social world, that I wish to investigate?

This question requires you to ask yourself what your research is about in a fundamental way, and probably involves a great deal more intellectual effort than simply identifying a research topic. Because it is so fundamental, it takes place earlier in the thinking process than the identification of a topic. It involves asking what you see as the very nature, character and essence of things in the social world, or, in other words, what is your ontological position or perspective. Ontology can seem like a difficult concept precisely because the nature, character and essence of social things seem so fundamental and obvious that it can be hard to see what there is to conceptualize. In particular, it can be quite difficult to grasp the idea that it is possible to have an ontological position or perspective (rather than simply to be familiar with the ontological components of the social world), since this suggests that there may be different versions of the nature, character and essence of social things.

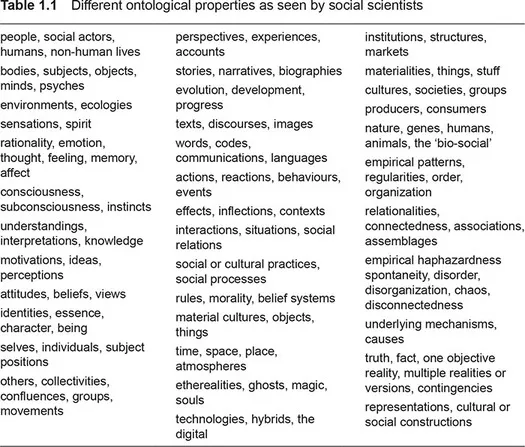

Yet it is only once it is recognized that alternative ontological perspectives might tell radically different stories, that a researcher can begin to see their own ontological view of the social world as a position which is – and indeed should be – formulated, understood and arrived at through a critical process. The best way to grasp that you have an ontological position, and to work out what it is and what are its implications for your research, is therefore to recognize what the alternatives are. Let us consider some examples. From different ontological perspectives the ‘social world’ might be made up of any of the following, as shown in Table 1.1.

This is not intended to be a complete list of social scientific ontological elements – and indeed listing them or trying to pin them all down is not really the point. Instead, the list is intended to suggest the enormous and exciting range of ways that social scientists might see the social world (actually, some would take issue with the ontological category of the ‘social’, but I shall continue to use it for convenience). The list is also intended both to tantalize you a little, and to help counsel you against taking such concepts and ideas at face value as though they are obvious or irrefutable facts: lying behind each of them are histories of propositions, arguments and challenges about what there might be to be explored, explained, imagined or theorized. Certainly, not all approaches would recognize the concept of ‘social world’ as ontologically meaningful; so, when we are discussing ontology, in a sense everything is at stake and nothing can be taken for granted.

So these and other concepts suggest different versions of the essential or component properties of what there might be (or the social world if you prefer), and different ideas about their shape, form and location as well as their singularity/multiplicity and objectivity/contingency. There are of course many different versions of whether and how these things might be said to be in relation to one another, and whether or not it is meaningful to talk of mechanisms or patterns in them. You will recognize some of these ways of conceptualizing social entities, and you may be able to connect them with different philosophies of social science. Some of the properties in Table 1.1 for example, and the distinctions between them, have been the subject of long-running disputes between positivists, interpretivists, feminists, realists, ethnomethodologists, postmodernists, anti-foundationalists, critical theorists and so on (see Howell, 2013).

At the very least, all of this should alert you to the possibility that different versions of ontology may be competing or even mutually negating, rather than complementary, so that you cannot simply pick and choose bits of one and bits of another in an ad hoc way and assume you can fit them together unproblematically. Of course you may actually want to actively pursue creative tensions between different ontogologies, or to follow a multi-dimensional approach which is interested to engage with more than one way of understanding the ontological world, and in that case you will not expect to find nor try to force a perfect fit between different positions. Some of the properties listed may appear more well-matched to qualitative research methodology than others, for example social processes, interpretations, social relations, social practices, experiences, stories and understandings seem particularly so. Some gain more credence in the conventions of some social science disciplines than others and there are changing fashions in the popularity and dominance of different approaches (Denzin and Lincoln, 2011; Howell, 2013). You therefore need to understand the implications of adopting a particular version or set of versions of ontology for your study.

This means that what is required is active engagement with ontological questions – or critical ontological thinking – to consider how they influence your take on what there is to be researched, and how you might go about it. Some researchers may feel unable to answer these ontological questions fully at the beginning of their research. Possibly this will be because they wish the research to address these very issues rather than simply to start from them, or even to attempt to adjudicate between some of the disputed distinctions. However, if that is so, then it should be an explicit research aim, formulated through research questions, since more often a reluctance to address these issues stems from vagueness or a failure to understand that there is more than one ontological perspective.

2. Knowledge and evidence: your epistemological position

- What might represent knowledge or evidence of the entities or social world that I wish to investigate?

- Am I being an ‘epistemological thinker’?

Questions about what we regard as knowledge or evidence of things in the social world are epistemological questions and, overall, this second question is designed to help you to think about and decide what kind of epistemological position your research expresses or implements. It is important to distinguish questions about the nature of evidence and knowledge – epistemological questions – from what are apparently more straightforward questions about how to collect, or what I prefer to call ‘generate’, data. Your epistemology is, literally, your theory of knowledge, and should therefore concern the principles and rules by which you decide whether and how social phenomena can be known, and how knowledge can be validated and demonstrated. Different epistemologies have different things to say about these issues, and about what the status of knowledge can be. For some, the concept of evidence itself is too categorical if that means that research can uncover or construct proof of universally perceived objective realities, instead of the more epistemologically modest and contingent concepts of perspective and argument.

Epistemological questions involve thinking about what you (and others) would count as evidence or knowledge of the kinds of ontological properties that you think comprise the social world. Therefore you should be able to connect the answers to these questions with your answers to the ontological questions so that the two sets are consistent. For example, if your ontological position proposes that the social world is comprised of behaviours, or practices, or experiences, or processes, or relationalities – then your epistemology should engage critically and productively with the question of what would constitute knowledge of these things, and how such knowledge could be generated (see Chapter 9 for a discussion of the construction of explanations and arguments. See also Crow, 2005; Howell, 2013, especially Chapter 12; and Saldaña, 2015a, Chapter 2). If you have made a study of the philosophy of the social sciences then you will know that there are many different ontologies and associated epistemologies. Box 1.1 gives examples of some of the most influential approaches, to help you to get a sense of how they are epistemologically distinct.

Box 1.1: Examples of epistemological approaches in the social sciences and what they imply about how knowledge is derived

- Ethnographic (researcher immersion/participation in settings – researcher generates knowledge through first-hand experience).

- Symbolic interactionist (meaning is found in situations and interactions – researcher needs to generate data on and through these).

- Phenomenological (the world, consciousness, perception and lived experience are inseparable, there is not an objective world that exists separately from our perception of it – researcher needs to explore this interconnectedness).

- Interpretivist (emphasizes the sense people make of their own lives and experiences – researcher seeks out and interprets people’s meanings and interpretations).

- Biographical, narrative, life history, humanist (researcher uses people’s personal life stories and biographical materials to document and understand biographies, personal life, histories, societies, cultures).

- Critical theory (life is determined through social and historical processes and power relations – researcher seeks to uncover these and question the taken-for-granted).

- Ethnomethodological, conversation analysis (researcher can trace and describe social orders through detailed analysis of everyday talk and interaction, following strict conventions).

- Psychosocial (researcher explores human psyches for signs that betray a subconscious or defended self in free association or unstructured/therapeutic-style interviews).

- Participatory/action research (the world is constructed through action, interaction and collective agency – researcher works with participants to co-generate knowledge and to create change collectively).

- Grounded theory (researcher should explore events, interactions and situations through immersion in data generation, and use their own agency in developing theory from the data using sensitizing concepts, not by applying a priori theoretical frameworks).

- Actor network, object relations, ecological (researcher looks for the ‘agency’ of actors which can be people, things and non-humans. Interest in the ecological layering of the social world).

- Realist/critical realist (the world is real and exists independently of our theories about it or perceptions of it – researcher looks for causes, or underlying mechanisms, and may also be interested in perceptions and interpretations because these are seen as part of the real world).

- Post-modernist, post-structuralist, anti-foundationalist (mounts a challenge to the authority of established rational theories and their claims to ‘truth’ and expertise, disputes the idea that there is one truth or reality – researcher aims to deconstruct established ways of knowing and dominant interpretations and discourses).

Box 1.1 does not cover all possible options, and there are overlaps and porous boundaries between some of the approaches, and (contested) barriers between others. Although it is useful ...