1.1 Development of Blackpowder

Blackpowder, also known as gunpowder, was most likely the first explosive composition. In 220 BC an accident was reported involving blackpowder when some Chinese alchemists accidentally made blackpowder while separating gold from silver during a low-temperature reaction. According to Dr Heizo Mambo the alchemists added potassium nitrate [also known as saltpetre (KNO3)] and sulfur to the gold ore in the alchemists’ furnace but forgot to add charcoal in the first step of the reaction. Trying to rectify their error they added charcoal in the last step. Unknown to them they had just made blackpowder which resulted in a tremendous explosion.

Blackpowder was not introduced into Europe until the 13th century when an English monk called Roger Bacon in 1249 experimented with potassium nitrate and produced blackpowder, and in 1320 a German monk called Berthold Schwartz (although many dispute his existence) studied the writings of Bacon and began to make blackpowder and study its properties. The results of Schwartz's research probably speeded up the adoption of blackpowder in central Europe. By the end of the 13th century many countries were using blackpowder as a military aid to breach the walls of castles and cities.

Blackpowder contains a fuel and an oxidizer. The fuel is a powdered mixture of charcoal and sulfur which is mixed with potassium nitrate (oxidizer). The mixing process was improved tremendously in 1425 when the Corning, or granulating, process was developed. Heavy wheels were used to grind and press the fuels and oxidizer into a solid mass, which was subsequently broken down into smaller grains. These grains contained an intimate mixture of the fuels and oxidizer, resulting in a blackpowder which was physically and ballistically superior. Corned blackpowder gradually came into use for small guns and hand grenades during the 15th century and for big guns in the 16th century.

Blackpowder mills (using the Corning process) were erected at Rotherhithe and Waltham Abbey in England between 1554 and 1603.

The first recording of blackpowder being used in civil engineering was during 1548–1572 for the dredging of the River Niemen in Northern Europe, and in 1627 blackpowder was used as a blasting aid for recovering ore in Hungary. Soon, blackpowder was being used for blasting in Germany, Sweden and other countries. In England, the first use of blackpowder for blasting was in the Cornish copper mines in 1670. Bofors Industries of Sweden was established in 1646 and became the main manufacturer of commercial blackpowder in Europe.

1.2 Development of Nitroglycerine

By the middle of the 19th century the limitations of blackpowder as a blasting explosive were becoming apparent. Difficult mining and tunnelling operations required a ‘better’ explosive. In 1846 the Italian, Professor Ascanio Sobrero discovered liquid nitroglycerine [C3H5O3(NO2)3]. He soon became aware of the explosive nature of nitroglycerine and discontinued his investigations. A few years later the Swedish inventor, Immanuel Nobel developed a process for manufacturing nitroglycerine, and in 1863 he erected a small manufacturing plant in Helenborg near Stockholm with his son, Alfred. Their initial manufacturing method was to mix glycerol with a cooled mixture of nitric and sulfuric acids in stone jugs. The mixture was stirred by hand and kept cool by iced water; after the reaction had gone to completion the mixture was poured into excess cold water. The second manufacturing process was to pour glycerol and cooled mixed acids into a conical lead vessel which had perforations in the constriction. The product nitroglycerine flowed through the restrictions into a cold-water bath. Both methods involved the washing of nitroglycerine with warm water and a warm alkaline solution to remove the acids. Nobel began to license the construction of nitroglycerine plants which were generally built very close to the site of intended use, as transportation of liquid nitroglycerine tended to generate loss of life and property.

The Nobel family suffered many set-backs in marketing nitroglycerine because it was prone to accidental initiation, and its initiation in bore holes by blackpowder was unreliable. There were many accidental explosions, one of which destroyed the Nobel factory in 1864 and killed Alfred's brother, Emil. Alfred Nobel in 1864 invented the metal ‘blasting cap’ detonator which greatly improved the initiation of blackpowder. The detonator contained mercury fulminate [Hg(CNO)2] and was able to replace blackpowder for the initiation of nitroglycerine in bore holes. The mercury fulminate blasting cap produced an initial shock which was transferred to a separate container of nitroglycerine via a fuse, initiating the nitroglycerine.

After another major explosion in 1866 which completely demolished the nitroglycerine factory, Alfred turned his attentions to the safety problems of transporting nitroglycerine. To reduce the sensitivity of nitroglycerine Alfred mixed it with an absorbent clay, ‘Kieselguhr’. This mixture became known as ghur dynamite and was patented in 1867.

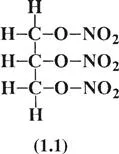

Nitroglycerine (1.1) has a great advantage over blackpowder since it contains both fuel and oxidizer elements in the same molecule. This gives the most intimate contact for both components.

1.2.1 Development of Mercury Fulminate

Mercury fulminate was first prepared in the 17th century by the Swedish–German alchemist, Baron Johann Kunkel von Löwenstern.

He obtained this dangerous explosive by treating mercury with nitric acid and alcohol. At that time, Kunkel and other alchemists could not find a use for the explosive and the compound was forgotten until Edward Howard of England rediscovered it between 1799 and 1800. Howard examined the properties of mercury fulminate and proposed its use as a percussion initiator for blackpowder and in 1807 a Scottish Clergyman, Alexander Forsyth patented the device.